Prof. Dr. Qasim Obayes Al-azzawi1 Asst. lect. Hasan Imad Kadhim2

Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Babylon

Email: dr.qasim_tofel@uobabylon.edu.iq

Department of English, Al-Mustaqbal University College, Hilla, Babil, Iraq

Email: hasan.imad@mustaqbal-college.edu.iq

HNSJ, 2022, 3(1); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj3110

Published at 01/01/2022 Accepted at 14/12/2021

Abstract

This paper aims at defining Conversation Analysis, as well as conversation. It also states types of interaction that an analyst might consider for the purpose of analysis. Get across turn taking and its principles. In addition, it concentrates on how a participant takes a role in conversations without overlapping others. Clarify rules and standards of politeness that have been developed by linguists such as Lakoff and Paul Grice. Examine how MPs of Australian Parliament switch turns in an interaction. Eventually, it tries to find out whether MPs follow the standards of turn-taking and politeness while taking a role in discussions.

Introduction

1.1 The Problem

Politeness is something very important to show someone’s ethics and social class attitude but the strange thing is that politeness is sometimes violated by high-ranked and educated people, so this paper tries to show these violated standards of politeness throughout breaking the standards of turn-taking conversational standards.

1.2 The Aims

This paper aims at:

– Defining Conversation Analysis, as well as conversation. It also states types of interaction that an analyst might consider for the purpose of analysis.

– Getting across turn taking and its principles. In addition, it concentrates on how a participant takes a role in conversations without overlapping others.

– Clarifying rules and standards of politeness that have been developed by linguists such as Lakoff and Paul Grice.

– Examining how MPs of Australian Parliament switch turns in an interaction. Eventually, it tries to find out whether MPs follow the standards of turn-taking and politeness while taking a role in discussions.

-

- The Hypotheses

The paper hypothesizes that turn-taking or role taking in Australian is violated most of the time.

1.4 The Procedures

To carry out the study these procedures are followed:

Explaining turn-taking and analyzing some extracted conversations in Australian Parliament.

1.5 The Limits The study is limited to Australian Parliament not any other parliaments.

1.6 The Significance

This study is hoped to be valuable for those who are interested in pragmatics and especially in Turn-Taking studies, as it surveys in some detail the use of turn-taking in Australian Parliament.

Literature Review

2. Introduction:

“Every good conversation starts with good listening” –Anonymous. Conversation can simply be defined as the act of exchanging information, ideas, and emotion via linguistic or non-linguistic symbols. Moreover, people maintain their social relationships by interacting with one another.

‘What is Conversation Analysis?’ Hutechby and Wooffitt (1998:13) define CA as “the study of talk. More particularly, it is the systematic analysis of the talk produced in everyday situations of human: talk-in-interaction”.

To put it in other words, CA aims at investigating human communication and how it works in multiple social settings. In addition, CA studies recorded and naturally occurring talk with the aim of finding out how participants understand and response to one another via taking turns at talk. It is noteworthy that CA deals with verbal as well as non-verbal interaction.

2.1 Turn-taking: Definitions

Turn-taking is one of the building blocks of conversation, i.e turn-taking is an essential element on which conversation is based. It is the process whereby speakers take a role in an interaction.

Hyland (2011:28) points out that “understanding how turn-taking … works in conversation is important for analysts both because co-conversationalist use turn-taking system to pass the conversational floor between them … and because participants can manipulate this normative system to bring off particular interactional effects … including displays of power”

Turn-taking draws neither on contextual factors (time and setting) nor on the characteristics of participants (age, sex, social class and the like). ” Turn-taking is context-free, that is, unaffected by these contextual particulars” (Psathas 1995:36).

It is worth noting that turn-taking between friends differs systematically from that between a student and his/her teacher. Because in the latter, classroom setting, has got some restriction on who may speak and when.

Interaction among family members can be tackled differently. Siblings of the same age do not follow certain rules when they talk. Their interaction thus is filled with interruptions. Additionally, they express their opinion freely without asking for permission.

On the contrary, parents-sons interaction is much more organized. Sons have to adhere to the principles of turn-taking. Moreover, they must not interrupt or overlap the current speaker. If they do so, their behavior is marked as impolite or rude.

Projectability makes turn-taking runs normally and it is defined as the listener’s ability to observe the current turn to know when will it come to an end. Projectability can be made via syntax and prosody. Let us deal with syntax, consider the following extract:

A. What is your name? B. John.

In the extract above, the first speaker uses an interrogative sentence that is followed by a brief silence so the second speaker realizes that it is the time to take the turn and to answer the question.

A participant can also predict his turn through prosody (the intonational aspect of language) :

A. Mam is here

B. I don’t know.

The first turn in the above extract is uttered with a rising intonation at the end to show that he is asking a question despite the fact that the sentence is not interrogative. The high rhythm of the first turn gives the listener a hint to start his turn.

The silence between two turns is known as Transition Relevance Place (TRP). Yule (1996:72) defines TRP as “any possible change-of-turn point … within any social group, there will be a feature of talk ( or absence of talk) typically associated within a TRP”

Turn Constructed Unit (TCU) is any sentence, phrase or lexical item in a conversation which form (construct) the turn. Let us consider the extract below:

A.They will come soon.

B. Whom?

A. My parents.

The turns, in the extract, can be a sentence (they will come soon), a phrase (my parents) or a word (whom).

Ultimately, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) adopted a number of rules that govern the process of turn-taking in conversation :

1. The current speaker might select a next speaker, then the next speaker must start

his turn.

2. If the first rule has not been made, any speaker has the right to construct the turn (self-selection).

3. If the first two rules have not been applied, the current speaker may continue to speak unless another participant self-selected.

These rules are not concerned with the kind of people involved in the interaction, what topic being talked about, the context in which turn-taking takes place, or the number of participants and the social relationship between them.

2.2 Turn-taking from Politeness Perspective

Politeness, in its widest sense, means respect. In different societies, people have diverse beliefs and practices. One is said to be polite if he shows deference to this diversity. In other words, politeness is to behave appropriately in different social situations and to have a kind and honourable social relationship with others. Principles of politeness differ among societies. That is to say, what is considered polite in your society may be considered impolite in another.

Pan(2000:5) argues that ”our ideas of how to be polite is the product of our socialization if people do not share the same discourse system … their perceptions of politeness and power relation will not be identical”.

Linguists adopt multiple rules of politeness. Lakoff, for instance, develops three principles :

1. Don’t impose: means avoid being obtrusive.

2. Give options: shows respect to the hearer.

3. Be friendly: creates intimacy between participants.

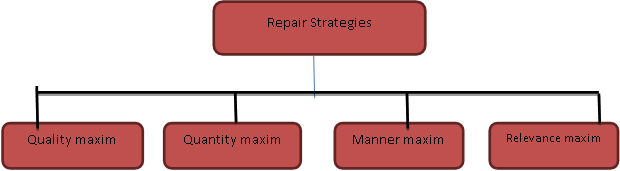

Likewise, Pual Grice adopts standards of politeness that are known as ”cooperative principles” or ” Gricean maxims”. In this respect, Gamble(2014;197) states that ”for both parties to be satisfied with a conversation, they need to cooperate. According to the cooperative principles, conversations are most satisfying when the comments of the conversational partners are consistent with the conversation’s purpose”. These maxims are:

1. Quality maxim: means that a participant must be adequate, i.e he/she should not say comments that are false.

2. Quantity maxim: a participant have to provide as much information as is

required to deliver the message.

3. Relevance maxim: a participant should not switch the main topic of the conversation.

4.Manner maxim: means the clearness of a participant’s speech.Simply, a speaker must not utter vague expressions.

Following the abovementioned principles and rules is what make one’s behaviour polite, modest, and appropriate. Let’s talk about our major topic which is the nature and system of turn-taking in the Australian Parliament. The one who always attends Australian Parliament sessions can easily note how problematic turn-taking is. This problematic nature results from the contrasting opinions among political parties. Members repeatedly accuse one another of not being honest and loyal. They consistently violate the principles of politeness. In the next section, extracts from the Australian Parliament sessions will pragmatically be analyzed.

Methods and Data Analysis

3. Model Framework

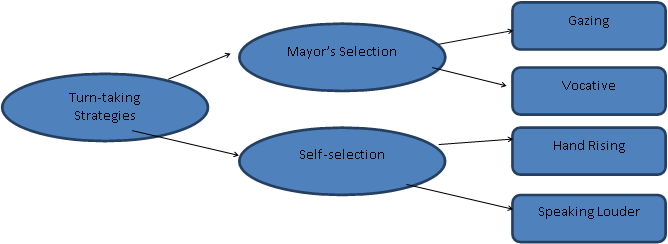

The model of analysis of the study is a developed model proposed by the researcher which frames the Turn-taking strategies.

Figure (1) Framework of Turn-taking Strategies

3.1. Data Analysis:

Extract No.1.

Speaker: be brief, please. [We don’t have

Mayor: [I am the only one who is asked to be] [brief

Speaker: [never]

Mayor: I must talk about 4 million people if you want me to be brief [I will leave

Speaker: [no, feel free]

Mayor: I will not speak in [brief

Speaker: [I did not mean it]

With reference to the definition of turn-taking and TRP, the participants in the above abstract pay no attention to these two fundamental aspects of interaction. Interruption, which is indicating by bracketing, is a recognizable feature of political discourse; in addition, it occurs five times throughout this short extract. Participants don’t give each other the chance to construct a meaningful and complete turn. Turns vary in length, Speaker, who is in a position of power, utters very simple, short, and syntactically incomplete sentences which implicitly reflect his weak personality and his inability to manage the interaction. Furthermore, there is an intentional misprojection. That is to say, that participant did not fail to project each other turn, rather they intend to do so: Mayor tries to positively represent himself as a spoke person and who cares the most about its criticizes.

Extract no.2:

Mayor: no one of Sidney officials stays at his house.

PM : Sir…

Mayor: my house has been burnt.

PM : you are THE MAYOR, [you should not leave the city at this critical time

Mayor: [listen to me please, sir]

PM : you are the head of the security committee [in Sidney

Mayor: [I know]

PM : [who runs Sidney at such a critical time?

Mayor : [let me complete my speech]

PM : you should not accuse other ministries as if they are [responsible for the crisis

Mayor: [I admit it is my responsibility]

Speaker: [ settle down, please

Pragmatically speaking, Maxim of relevance (the participant should not switch the main topic of the conversation) has been violated during the first four turns. Whereas the Mayor says that his house has been burnt, PM switches the topic and starts to blame Mayor for leaving the city at such critical time. PM, who is the dominant person in interaction, construct semantically and syntactically complete sentences which reflect his powerful status. Another way of displaying power is the use of prosodic feature: intonation as in [ THE MAYOR]. Furthermore, PM uses the strategy of accusation, i.e. (According to ( Castor, 2015:1) accusation are assertions which indicate that someone has done something wrong). The accusation here takes the form of a statement [You should not leave…..] and a question [who runs Sidney at such a critical time?]. Interacting with Speaker, Mayor of Sidney dominated the participation and hardly allow Speaker to construct a complete turn. By contrast, in this extract, he asks PM to take the turn :[listen to me, please], [let me complete ..]. Thus Mayor takes the social status of others into consideration.

Extract no3.

MP :the Ministry of Municipalities is incompetent and does not follow up its

Action.

Minister: have you been aware of the [Ministry’s activities?

MP : [ I am a former governor and familiar with it

Minister: does the provincial council visit the project?

MP : don’t let these deficiencies [reflect on the Government activity!

Minister: [I can’t allow you!

Mp : Mad’m!

Minister: I CAN’T ALLOW YOU!

Speaker: Don’t interrupt him

MP : your ministry has a negative impact on Government

Minister: the performance of the Ministry is CAPABLE!

Member of Parliament (MP) and the Minister use the strategy of positive self-presentation and negative presentation of others: a strategy proposed by Teun Van Dijk (1993) which involves expressing negative information about others (Oktar, 2001). Both of them try to accuse the other of not performing their duties appropriately.

MP and Minister’s turns are almost equal in length which might indicate that they have got the same level of power and/or social status. Words, that are written in capital letters, indicate that the participant speaks with a high-pitched voice as a way of defending herself and her ministry.

Participants take turn respectively. The Minister’s first two turns are constructed in the form of a question [have you been aware of the Ministry’s activities?] [does the provincial council visit the project?]. She addresses her questions to MP because she wants him to provide answers without making unreliable accusations. The MP, in turn, does not answer her questions and thus violates the principles of relevance.

Despite the fact that Speaker tries to settle down the argument but unfortunately none of them pays him attention. This indicates that Speaker is incapable of controlling the interaction.

Finally, Miniter repeats the phrase [ I can’t allow you] twice. She uses the same lexical items and syntactic construction because she becomes angry and bad-tempered.

Extract no.4:

MP1: Speaking to you from this podium of the Australian representative among the most suffering peoples, Sidney is the greatest! It is the capital of Australia. It was the capital city of the world.

MP2: I would interact with her for what has been said about his refusal for the despotism and tyranny , but I disagree with him when he wanted to comment a virtue over the capital, By commenting on a stain over the capital, whenever referring to them, those who killed [And their judgment were based on the oppression and killing.

MP3: [Don’t be sectarian!

MP2: No, it’s not a Sectarianism! [Sectarianism is when you defend a tyrant.

Speaker : [Sir !

Speaker: We are all Australians here, we have to call positive messages for all the Australian people.

It is quite obvious that there are religious thoughts embedded within the above political discourse. The first participant points out that Sidney was considered as the capital city of the world at this time, but in the present time, Australian people are suffering too much. Despite the fact that the first turn is not addressed to MP2 but he constructs a very elaborated turn. MP2 produces a preferred comment when he agrees with MP1 that Australian people suffer the most. He also constructs a dispreferred comment introduced with ‘but’, which reflects that the upcoming utterances are in contrast with the aforementioned ones, when he turned the discussion into a religious one.

Pragmatically speaking, MP1’s comment might presuppose that he belongs to a certain religious sect. Furthermore, he may have the intention of gaining the trust of those people who belong to the same sect.

Syntactically speaking, MP3 constructs a sentence starts with a verb which indicates that he is either commanding or asking the other member to stop saying sectarian expressions. MP2, on the other hand, attacks and accuses MP3 of defending tyrants.

It is noteworthy that the first two turns run normally. However, interaction turns into a chaos when MP2 changes the real and the main topic of the discourse. Consequently, other members feel the need to have the conversational floor in order to express their anger and disagreement with that member.

The strategy of accusation is also clear in MP2’s words [Sectarianism is when you defend a tyrant !]. If we recall Grice’s definition of cooperative principles ” conversations are most satisfying when the comments … are consistent with the conversation’s purpose”, we get the idea that MP2’s turns are inconsistent. On the contrary, Speaker provides a very compatible and harmonious turn through which he aims at controlling the discussion and leading it to an end.

Finally, Quantity Maxim has been violated by MP2 because he provides an unnecessarily detailed turn which, in fact, does not convey an information adhered to the current topic.

Conclusions

Definitions of conversation, principles of politeness, and turn-taking have been tackled throughout the theoretical part of this paper. In addition, these concepts are taken into consideration while analysing extracts taken from Australina Parliament sessions. The paper aims at finding out whether or not MPs adhere to such principles while participating in political debates or/and sessions.

Relevance Maxim, as it turns out, has been violated many times in the abovementioned extracts. In extract no.2, for instance, PM’s turn [you are THE MAYOR, you should not leave the city at this critical time] has nothing to do with the turn that precedes it, which is produced by the Mayor of Sidney [my house has been burnt].

TRP (Transition Relevance Place), which refers to a brief silence, or a point of transition between two turns, is almost absent in the extracts that have been analysed. In extract no.3, for example, Minister tries to construct a question but MP does not wait until she finishes her turn:

have you been aware of the [Ministry’s activities?

[ I am a former governor and familiar with it

Moreover, principles of politeness, that have been proposed by Lakoff, are rarely found here. Impolite responses can be marked in extract no.4 [Sectarianism is when you defend a tyrant.] and extract no.3 [ your ministry has a negative impact on Government] Principles of politeness are, however, marked in some tuns. In extracts no.1, when Speaker tries to soften the blow of Mayor’s responses by repeating the idea that he does not want to prevent him from expressing his points of views: [never], [ no, feel free] [ I did not mean it]. In addition, MPs, who are in a low position of power, tend to respond politely. In extracts no.2, PM accuses the Mayor of being the one who is responsible for the crisis of Sidney; however, Mayor responses politely [listen to me please, sir].

Finally, participants intentionally misproject one another’s turn via interruption. Overlapping is the most prominent feature of the Australian Parliament Session. It is worth mentioning that participants interrupt one another more than eleven times.

References

Castor, T. (2015). “Accusatory Discourse”. In Sandel, T. and Ilie C.

Gamble, T. K. (2

014). Interpersonal Communication: Building Connection Together. United States of America: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Oktar, L. (2001). The ideological organization of representational processes in the presentation of us and them. Discourse and Society.

Paltridge, K. H. (2011). Continuum Companion to Discourse Analysis. India: British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

Pan, Y. (2000). Politeness in Chinese face-to-face Interaction. United States of America: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Psathas, G. (1995). Conversation Analysis: The study of Talk-in-Interaction. United States of America: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Wooffitt, I. H. (1988). Conversation Analysis. USA: Blackwell Publishers Inc.

Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Web sources:

•The extracts are taken from