Prof. Dr. Salih Mahdi Adai Al-Mamoory1 Hasan Ali Hussein2

English Department, College of Education for Human Sciences, Babylon, University, Iraq.

Email: salih_mehdi71@yahoo.com

2 Department of English, Mazaya University College, Iraq.

Email: hass29000@gmail.com

HNSJ, 2022, 3(1); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj3146

Published at 01/01/2022 Accepted at 27/12/2021

Abstract

The present paper mainly aims to investigate and explore how English is presented and represented in comparison to Arabic and other non-Arabic languages (if there is any) in different selected regions of Iraq. The data in this work consists of (221) public sector Linguistic Landscape (LL hereafter) markers and have been collected from different Iraqi cities, namely An Nasiriya, Karbala and Baghdad. With its four strategies: duplicating, fragmentary, overlapping, and complementary, Reh’s (2004) model has been found suitable to be applied to the data in hand. Not to mention that the concept of multimodality proposed by Norris (2020) also has been found relevant to respond to the nature of the collected data in the analysis. That is to say, going beyond word-based analysis of the collected datasets and further consider other non-verbal (visual) elements of the LL markers give the hint that Iraqi culture might be considered as a bilingual society.

However, this study hypothesizes that languages could be verbally or non-verbally displayed on the Linguistic Landscape signs across different Iraqi geographical regions, specifically in the center and south of Iraq. It also hypothesizes that the vast majority of visitors, who share different linguistic and cultural knowledge, enhances their nature with regard to their history and economy. Hence, this might show that Iraqi society is a bilingual one though its people hold one or at the most two different languages: Arabic and Kurdish. As for the record, Kurdish is specifically used by people who live in the north of Iraq. Putting forward a third hypothesis, the presence of different multimodal signs with different languages is socially symbolic where it implicitly reflects the sense of globalization, language policy and ecology.

Key Words: landscape markers, multimodality, globalization and social identity.

1. Introduction

The language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combines to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration (Landry and Bourhis, 1997: 25 cited in Banda et. al 2019: para 3).

As mentioned above, most of the LL-related research put much weight on cities signposts, shop signs, a point of which LL is at its densest in cities where signage fulfilling various purposes ranging from ‘informative’ (top-down markers) to ‘transgressive’ type (public signs in terms of placement as in graffiti) (Scollon and Scollon 2003: 146).

Going back to the historical origins of LL, Coulmas (2009: 8-13) argues that the visible languages in public is as old as writing represented in the Codex Hammurabi from Iraq, the Rosetta Stone from Egypt, the Behistun from Iran, Menetekel, and The Taj Mahal from India as five known ancient sites for archaeological inscriptions.

Corter, (2013: 190-1), states that LL studies have expanded to involve some other semi-public sites of which museums, libraries, schools, hospitals and the like are just mere examples. This leads to the exploration and understanding the nature of the written texts in ‘urban’ spaces mostly featured as bilingual and bilingual characteristics. Via considering other new forms of signs, such characteristics are currently made available by technological developments, such as electronic flat-panel displays, interactive touch screens, electronic message centers, foam boards, etc. (ibid). As a result, this paper addresses certain questions as what follows:

- Is Iraqi culture regarded as a bilingual society in terms of one of the strategies proposed by Reh (i.e.,duplicating, fragmentary, overlapping, and complementary)?If so;

- How are different languages represented? Do they follow a particular process? And in what forms in the settings under study?

- What are the main features LL markers in those cities?

2. Bilingual Approach

In 2004, Reh developed a model to study and categorize bilingual writings as observed in the streets. This model, knows as the frame of interaction, consists of three aspects: (1) spatial mobility of signs, (2) visibility of bilingualism, and (3) information arrangement on signs. the second and third aspects are seen to be more applicable to the collected bilingual markers within the scope of ‘visible bilingualism’ (see Reh, 2004). This helps to explain the way in which information is organized and presented in bi/bilingual texts as part of the LL markers within the broader lines of this paper.

However, Reh (ibid) identifies four major types of bilingual arrangement: a. duplicating, b. fragmentary, c. overlapping and d. complementary. Types (a), (b) and (c) are referred to those signs in which the languages included either completely (a) or partially (b and c) constitute mutual translation of each other. Nevertheless, type (d) gives two or more languages showing completely different kinds of content. The fundamental difference between types (a), (b), (c), and (d) is that the latter (d) requires a bilingual reader if one needs to understand completely, while the other three types do not.

Putting it in another way, Reh (2004: 8-14) has best described these four types in a vividly:

- Complementary bilingual information: The text is composed in multiple languages. To understand the message fully the speaker must possess knowledge of all languages presented. By doing so, particular information cannot be accessed by a monolingual speaker (Reh 2004: 14)

- Fragmentary bilingualism: The text is given in one language but selected information is translated into another. The purpose is to draw attention of a speaker with limited knowledge of the translated language. This type of information arrangement also addresses speakers focusing on keywords (Reh 2004: 10).

- Duplicating bilingual information: The exact same text is presented in more than one language. Here, the information is presented to a target speaker which cannot be reached by one language only (Reh 2004: 8) – It can also be used for educational purposes.

- Overlapping bilingual information: There are two types of texts: One text offers additional and/or similar information to another text. Monolingual speakers can derive the information of only one text while bilingual speakers receive additional information from both texts (Reh 2004:12).

2.1 The Concept of Multimodality

In an increasingly globalized world, communication has become more characterized with the use of different modes and languages (see Canagarajah 2013). This has extended to include different fields of life, in which LL discourses are no exception. It has become common that streets are more amalgamated with signs of various modes to accomplish meaning beyond language. This is quite often represented in the use of both verbal and non-verbal semiotic resources (i.e., word-only, image-only and image-word LL markers). Norris’ (2020) multimodality of interaction has been adopted here to further capture how different semiotic units (images or other directive symbols and drawings) could interactively work with linguistic ones in the collected data of this work. In addition to Reh’s (2004) model, Norris’ multimodality serves to describe the way(s) in which different semioses combine with LL signs, reflecting a particular kind of relationship between the given language(s) across different places and their inhabitants. Furthermore, Norris (2020: 1-5) provides a possible means in this work to explore only images of LL markers, a matter which Reh’s model by itself does not contribute that much in this paper.

2.2 Top-down and Bottom-up Markers

Ben-Rafael et. al (2006) examine signs in a ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ dichotomy. The former refers to the public and institutional signs and the latter refers to the private and individual ones. The distinction between top-down and bottom-up signs is another factor which contributes to the comprehension of language policy. Later on, Ben-Rafael (2009: 49) emphasizes that the distinction between top-down and bottom-up signs is significant because different signs are made by different actors for different audiences, and while top-down signs “serve official policies”, bottom-up signs “are designed much more freely”.

3. Research Methodology

With all what has been just mentioned in mind, this paper focuses on analyzing LL markers in three Iraqi cities: An Nasiriyah, Karbala, and Baghdad. As for why the researcher decided to choose these geographical areas in particular, it goes beyond the fact of the vibrant nature of these cities. These cities have shown, by virtue, their history, economy and a number of residents. Besides, those visitors, who come from different places of the world, have their own tourism in such cities, and thus have their own different linguistic and cultural backgrounds reflected in the Iraqi culture.

However, a qualitative approach, with the use of multimodal discourse analysis, is used to describe and analyze the collected data. The data in this paper consists of (221) LL markers collected from different streets of those three cities mentioned previously. Following the steps of Sarah Williams (2020: 50-55), electronic pictures of the LL markers were taken and scratched-together from the streets. The process ends with (221) digital images of the markers across the respective cities. As for the tool the researcher used to capture his data, the iPhone X Max Camera did the task.

More importantly, the researcher has taken into account the ethical issues into consideration. The researcher did his best in respecting the privacy of the shop owners and in asking those owners for their permission to use the data under investigation.

4. Data Analysis and Results

Each marker was considered individually, and then distinguished according to its language, and whether it was monolingual, bilingual or bilingual, composed of words only or words plus images. Beside these criteria, the data recorded in the Iraqi LL were categorized depending on Reh’s model (2004) as ‘duplicating’, ‘complementary’, ‘fragmentary’ and ‘overlapping” bilingual writing, and non-standard English occurrences. Also, markers composed of words plus images which are examined according to Norris’ (2020) model. The data in this work, however, consists of (221) signs. They were all categorized due to their content with reference to the used models of analysis. This work, whatsoever, focuses only on those LL markers that display visible bilingual discourses.

Furthermore, the collected data are grouped in a corpus, and further analyzed by the sign or marker type, i.e. top-down and bottom-up signs. Table (1) presents that while the four major types of bilingual arrangement are involved in the inscriptions of bottom-up signs, only the two strategies of duplicating, and fragmentary are presented in top-down signs but overlapping and complementary bilingualisms are not.

Table (1) Types of bilingual arrangement

| City | Duplicating | Fragmentary | Overlapping | Complementary |

| An Nasiriya | 23 | 2 | 4 | 8 |

| Karbala | 59 | 11 | 7 | 11 |

| Baghdad | 43 | 18 | 16 | 19 |

| Total | 125 | 31 | 27 | 38 |

| Overall Total= 221 | ||||

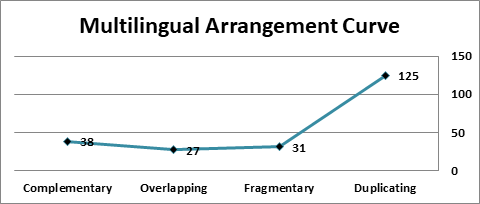

Figure (1) Bilingual Interactional Curve

Following the table and the figure plotted above, it is clearly noted that the exemplified markers of duplicating and complementary bilingualism are much more frequent than those of fragmentary or overlapping bilingualism. The analysis, however, shows that the overwhelming majority of sings contain duplicating and complementary bilingual writings while fragmentary or overlapping bilingualisms represent the lowest number of signs in the cities under study.

Table (2) Distribution of bilingual strategies by marker interaction category

| City | Top-down | Bottom-up | Total | |

| An Nasiriya | 17 | 23 | 40 | |

| Karbala | 22 | 47 | 69 | |

| Baghdad | 14 | 98 | 112 | |

| Total = 221 | ||||

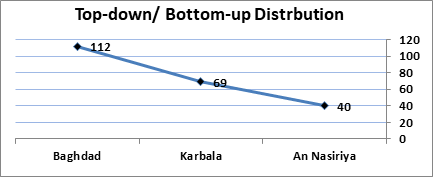

Figure (2) The Distribution of Top-down/ Bottom-up Markers

When the matter goes further to deal with the distribution of signs in An Nasiriya, Karbala and Baghdad, a distinction between top-down and bottom–up markers should be made. Thus, such a distinction lies in the fact that duplicating bilingual information represents the highest frequency among the former whereas it is not the case with the latter. This occurs because of the local municipality of language policy where the majority of top-down markers are prepared bilingually in Arabic and English and in the same time information in Arabic are rendered into English.

In the coming few pages, the four strategies of bilingual information will be clarified individually with appropriate illustrations from the collected data. This will be done by manipulating some of the LL themes peculiar to the public space of Iraq in terms of the different cities under investigation.

4.1 Duplicating Bilingual Writing

Duplicated bilingual LL discourses has come to be identified as a prominent theme across the areas under study. The same message in the LL top-down marker is exactly expressed with the use of different languages, see the following figure:

Figure (3) Duplicating bilingual writing in Thi-Qar (top-down)

The information duplicated here reflects the echo of the government institution as all information (except the logo) in French is translated into Arabic. The first prominent logo is in French (Liberte, Egalite and Fraternite) and is set on the top for emphasize. The symbol (woman’s face) of the consulate is designed in the middle, a matter of attraction related to portray the three words of the slogan. Still, the white colour of the face matches the logo presented under (i.e., Freedom, Equality and Fraternity). This shows the paramount communicative role of French compared to Arabic. All the scripts, below the title, are written in equal size and centered as well as having the same colour of the French flag.

Duplicating bilingual writing corresponds to what Backhaus (2007) terms as ‘homophonic signs’, which show complete translation or transliteration of two different languages. This means that all codes are exact translations. See the following figure:

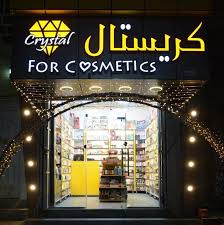

Figure (4) Duplicating bilingual writing: A commercial enterprise in An Nasiriya

(bottom-up)

The marker text in this figure, for example, includes two pieces of information: Crystal for Cosmetics in white colour and ( كرستال) in yellow which is the exact translation of part of the English name on the left.

Reh (2004: 8-9) argues that duplicating bilingual writing is used when not all members of the target group can be reached by a monolingual message or when the sender wants to reach a particular target group, such as tourists, businessmen, etc. In this sense, duplicating bilingual information functions as an identity marker and reflects the equality of all the linguistic and cultural communities addressed. Another possibility, it holds a fact that in the case of duplicating texts used in the Iraqi LL where English inscriptions are meant for tourists and foreigners. Shop owners, in this regard, are keen on to convey the whole message in English to the reader.

4.2 Fragmentary Bilingual Writing

Fragmentary bilingualism occurs when only a part of the information or message is translated into other languages. Using Reh’s (2004: 10) words, “the term fragmentary bilingualism is used for bilingual texts in which the full information is given only in one language, but in which selected parts have been translated into an additional language or additional languages.”

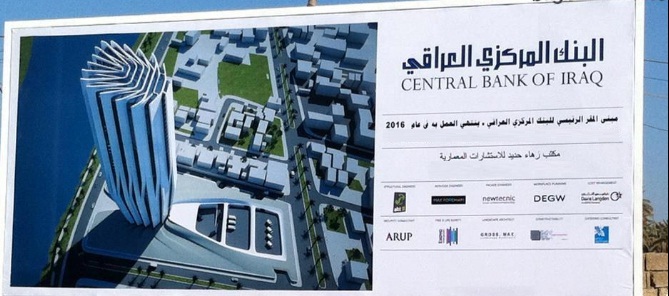

Figure (5) Fragmentary bilingual writing: A bank in Baghdad (top-down)

The multifunctional billboard in Figure (5) is a prime example of fragmentary bilingual information. It is fragmentary due to the fact that only one part of the inscription is converted into English, that is the name of the bank (Central Bank of Iraq) on the top, while the other parts are in Arabic: the second line is a kind of advertising slogan meaning “the building of the bank will end in 2016”, the third line tells us that the bank was designed by Zaha Hadid.

Figure (6) Fragmentary bilingual writing: A dentist’s clinic in Baghdad (bottom-up)

The sign in Figure (6) is another interesting instance of fragmentary bilingualism, whose complete text is written in Arabic, while one part of the text is inscribed in English; it is obvious that Arabic is more prominent than English by virtue of complete edition.

4.3 Overlapping bilingual writing

Overlapping bilingualism is not very frequent. Only (27) overlapping markers are found in the data. Overlapping bilingual writing means that only a part of the message is repeated in another language. Even though Reh (2004) draws a distinction between fragmentary and overlapping bilingual texts, Backhaus (2007) regards the both types exactly the same and terms them as ‘mixed signs’.

Figure (7) Overlapping bilingual writing: A governmental institution in Thi-Qar (top-down)

It is clear that the original language of the sign is Arabic. This is indicated by introducing the name of the governmental institution in Arabic and placing it on the top. This is the only part that is translated from Arabic into English (i.e., The Independent Electoral commission of Iraq). The other part remains in Arabic without any translation (e.g.,مكتب انتخابات ذي قار (.

Figure (8) Overlapping bilingual writing: A commercial company in Baghdad (bottom-up)

The overlapping practice in Figure 8 lies in the insertion of the slogan “REAL TIME VEHICLE TRACKING . . . WE TRACK YOUR VEHICLES”. Appearing exclusively in English, the slogan functions as a sign of glocalisation where the local brand name “REAL TIME VEHICLE TRACKING” is combined with the local slogan mentioned above. The other portions of the sign are in Arabic with only the name of the company is converted into English (i.e., ELECTRONIC INDUSTRIES COMPANY).

4.4 Complementary bilingual writing

Complementary bilingualism occurs when the different parts of the message are in different languages. In such a case, one has to be familiar with all the used languages in order to understand the sign. The difference between overlapping and complementary bilingualism is that there is some repetition in overlapping bilingualism and none in complementary (Reh, 2004: 14).

.

Figure (9) Complementary bilingual writing: A commercial shop in Karbala

(bottom-up)

The multifunctional sign in Figure (9) is a typical example of complementary bilingualism. It employs three different languages: English, Arabic and Iranian. The sign involves three portions designed for a set of advertising purposes. In the middle, appears the shop name in Iranian only which means “Iranian Carpet”. The portion on the right side is in Arabic. As for the left side of the marker, it is exclusively in English with Arabic slogan under it. Such a slogan is set here for attracting the attention of the buyers.

Figure (10) Complementary bilingual writing: A commercial shop in Karbala

(bottom-up)

The marker in Figure (10) is also another illustration of complementary bilingual writing. It is complementary in that it shows two different pieces of information in two different codes, that is English and Arabic. The name of the restaurant is solely in English (eat & go) on the right side corner while the slogan in Arabic on the left side at the bottom advertises the service which reads. Unless the reader is bilingual in both English and Arabic, s/he will not be able to fully receive the message of the sign. The two semiotic images of the “Falafel” and that of the name of the restaurant help decode the two different codes of the text.

The use of Arabic and English here is meant to emphasize the importance of modernity, good quality and reconciliation with the local community in Karbala. Furthermore, in this multimodal image, the message here is expressed by using different modes, words (e.g., Falafel and Burger) and images of food (i.e., falafel, vegetables and tomato). Thus, this is what ‘fast food’ means for the restaurant to complete the meaning of the marker to viewers or readers.

5. Discussion

[M]onolingual countries were always an exception, but globalization with its ensuring migration flows, spread of cultural products, and high spread communication has led to more bilingualism. In current approaches to bilingual writing, written languages are the focus of the LL studies. (Cenoz and Gorter, 2008: 270)

With the block quotation mentioned above in mind and despite the fact that speech community in Iraq is generally monolingual in Arabic, the public space of Iraq is primarily bilingual. This might be due to the fact that Iraq has been influenced by certain processes such as modernization and globalization via mainly the use of English.

As it is previously done in the analysis, duplicating strategy has scored the highest degree of bilingual writings in the three cities under study (see Table 1). To this end, the researcher is going to use the duplicating strategy as a piece of evidence for investigating bilingual information that happens to occur in those cities. In other words, duplicating strategy can be used to show the city whose residents use bilingual scripts the most.

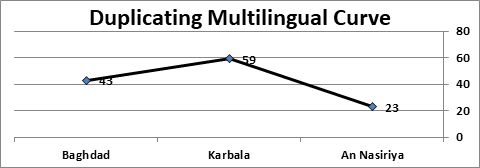

Table (3) Duplicating Bilingual Writings

| City | Duplicating |

| An Nasiriya | 23 |

| Karbala | 59 |

| Baghdad | 43 |

| Total | 125 |

Figure (11) Duplicating Bilingual Writings in Three Cities

Taking the table and figure plotted above into account, it can be clearly noted that ‘Karbala’ has scored the highest degree of duplicating bilingual writings (i.e., 59 LL), making it located in the first place; whilst ‘Baghdad’ is located in the second place scoring (43) LL. As for ‘An Nasiriya’, it scores the least degree of LL in terms of its duplicating information (i.e., 23).

With all this in mind, many foreign tourists travel to Iraq, and specifically to the cities mentioned under investigation. Where foreign tourists of different nationalities, for example, go and stay for long periods in An Nasiriyah, they aim to work on archaeological excavations in Thi-Qar province but the truth is that their presence in the streets for the sake of shopping is very little. That is why the researcher saw, from the analysis resulting from this study, that LLs in An Nasiriyah achieved the lowest rate of duplicating bilingual scripts.

As for turning the steering wheel to the city of Baghdad, the researcher found that the number of these duplicating writings has increased. This indicates that the sellers in the street and shop owners speak different languages. It is a fact that might be because of the visitors or tourists who are of different nationalities, especially their presence in the holy places, particularly the shrines of Al-Jawadain (PBUT) . When the matter goes to Karbala city, these duplicating scripts has reached the highest rate of LL. For the same reason, one may see that many sellers and/ or shop owners speak multiple languages, including Iranian and/ or English in addition to Arabic. As a concluding word, the need for sellers to write on their billboards, in all cases, leads to attracting the attention of foreign visitors or tourists.

6. Conclusions

Rounding off this study, the conclusions are listed down below:

- A close investigation of public space of Iraq, specifically those of An Nasiriya, Baghdad and Karbala, has revealed that the LL in Iraq is much more bilingual than one may expect. Paradoxically speaking, while speech community in Iraq is monolingual in Arabic, the LL there is characterized by bilingualism.

- In applying Reh’s (2004) reader and/or viewer-oriented theoretical model of bilingualism, data analysis shows that the four strategies of bilingual information are verified with various degrees of manifestation. Duplicating and fragmentary bilingualisms score higher frequency than overlapping and complementary bilingual scripts in both bottom-up and top-down signs.

- The non-existence of complementary bilingual scripts in top-down markers could be more engaged with language policy used by the local authority, a policy that doesn’t demand using a wide range of foreign languages and language varieties not publically permitted on officially-related signs.

- The overlapping strategy has scored the least rate of LL. Its lack of occurrence may implicitly give an indication of monolinguality in a particular LL context.

- Since it has scored the highest degree of bilingual writings in the three cities under study, the duplicating strategy can be used to show the city whose people use bilingual scripts the most.

- The widespread of English in public life has made it possible that English is used as popular mediums for expressing fondness in Western culture, especially among affluent classes. Linguistic glocalisation in our context refers to the use of international elements together with local ones serving the purpose of adding some kind of advertising power to the slogans in Arabic and English.

- Finally, this study leaves the door open for conducting further investigations in this field of research. The LL of Iraq still needs to be further researched and studied from diachronic or comparative perspectives with other Arab countries.

- The markers or signs that happen to occur in universities, hospitals, malls, store departments, movable markers, posters, and advertisements, might be of an interesting area of investigation in this regard.

Reference List

Backhaus, P. (2007). Linguistic landscapes: a comparative study of urban bilingualism in Tokyo. Clevedon: Bilingual Matters.

Banda, F., Jimaima, H. and Mokwena, L. (2019). ” Semiotic Remediation of Chinese Signage in the Linguistic Landscapes of Two Rural Areas of Zambia”. In Sherris, A. and Adami, E. (eds.) 2019. Making Signs, Translanguaging Ethnographies: Exploring Urban, Rural and Educational Spaces. United Kingdom: Bilingual Matters.

Ben-Rafael, E. (2009). ”A sociological approach to the study of linguistic landscapes”. In: Gorter D. and Shohamy E. (eds.). Linguistic landscape: expanding the scenery. New York: Routledge, 189-205.

Ben-Rafael, E., Shohamy, E., Amara, M., and Trumper-Hecht, N. (2006). ”Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel”. International Journal of Bilingualism, 3 (1), 7 – 30.

Canagarajah, S. (2013). Agency and power in intercultural communication: Negotiating English in translocal spaces. Language and Intercultural Communication. 13(2). 202- 224.

Cenoz, J. and Gorter, D. (2008). ”Linguistic landscape as an additional source in second language acquisition”. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46, 267- 287.

Coulmas, F. (2009). ”Linguistic landscaping and the seed of the public sphere”. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.). Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp.13-24). New York, NY: Routledge.

Gorter, D. (2013). ”Linguistic Landscapes in a Bilingual World”. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 33, 190–212.

Norris, S. (2020). Multimodal Theory and Methodology: For the Analysis of (Inter)action. New York: Routledge Books.

Reh, M. (2004). ”Bilingual writing: A reader-oriented typology – With examples from Lira Municipality (Uganda)”. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 170, 1–41.

Scollon, R. and Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge Books.

William, S. (2020). Data Action: Using Data for Public Good: How to use data as a tool for empowerment rather than oppression. Cambridge: MIT Press.