Prof. Qasim Abbas Dhayef Ph.D.1 Asst. lect. Hasan Imad Kadhim2

Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Babylon, Iraq

Email: qasimabbas@uobabylon.edu.iq

Department of English, Al-Mustaqbal University College, Hilla, Babil, Iraq

Email: hasan.imad@mustaqbal-college.edu.iq

HNSJ, 2022, 3(1); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj319

Published at 01/01/2022 Accepted at 14/12/2021

Abstract

Exaggeration is very common in language as the term ‘hyperbole’ refers to such a kind of figurative language. Hyperbole is regularly and widely used in sport commentaries in certain moments of excitement, for instance, when making an amazing shoot and an overreaction of a skillful move. Furthermore, the present paper tries to investigate the uses of hyperbolic expressions in both English and Arabic sport commentaries specifically football commentaries from pragmatic perspective by analysing three different texts by different commentators in both languages. The study concludes that hyperbolic expressions are highly manifested in both English and Arabic commentaries, however, Arab commentators tend to use exaggerated statements more than English do.

From the lexicological point of view, the language of the sport can be treated as a “specialized language” according to its linguistic features that are present in various linguistic levels. It can be defined as “the linguistic representation of sporting activity” (Taborek, 2012:238). It is connected in the eighteenth century with the history of journalism (Spurr, 2001:82). At the end of the nineteenth century and with the emergence of industrialization of the newspaper, sport reporting is found in the last pages of the journals (ibid.), so that the study of sport language is connected with the study of journalism.

Crystal and Davy (1969: 145) refer to the fact that sport commentators (henceforth) Com. (s) can easily achieve “economies of grammatical structure” to reduce repetitiveness and increase the “descriptive immediacy on which they so much rely for effect” (ibid.). The football Com.(s), for instance, insert clipped syllables which are articulated in a speedy way more than usual for the purpose of emphasis and to indicate important events (ibid.:154). Therefore the features of paralanguage are varied in sport commentaries. For the fully and effectively achievement of this skill, the audience have to be familiar with the game as well.

According to Ferguson (1983: 153), the most distinctive features of sport commentary are the paralinguistic features of language, for example, intonation, speed and pitch. He argues that sport Com.(s) often change the level of speed, pitch, or intonation according to the level of their excitement. These features are used in order to increase the level of excitement and to convey the audience emotion (ibid.).

When Ferguson was teaching his students how to analyse register in a sociolinguistic seminar, argues that lexical and phonological features of sport language are different from other registers and even between different sports themselves. He, in his seminar, focuses mainly on lexical variables and identifies the register variables. He defines broadcasting as “the oral reporting of an ongoing activity, combined with provision of background information and interpretation” (ibid.: 156). He describes that kind of language used in broadcasting either as a monolog or a dialogue directed towards an unknown audience who neither sees the game nor respond to the reporting. In his syntactic analysis of sport language, he identifies six variables. They are:

1- Simplification: It includes the omission of the initial noun phrase in the sentence, the noun phrase and the copula, post-nominal copula as well as the indefinite articles. He adds that these omitted elements can be easily recovered, for example: [He’s] having a drop back to find possession (ibid.: 159).

2- Inversion: It is done due to the time constraints of broadcasting as the action is more important than the player’s identity. It includes the inversion of the positions of the names of the players in the sentences from its initial position into postposition while preposing the predicate, for example, Comes in a little bit late there and misses the ball . The verbs that are usually used in such sentences are copula but may also verbs of motion. It works as a register marker since the player’s identity is readily available in almost all sports (ibid.: 161).

3- Result expressions: Ferguson (ibid.) points out a pair of constructions that marks final results. They are for + noun and to+ verb. These forms come as a result of time constraints (ibid.: 162). For example, Gallas stuck with a run track to every inch of the way.

4- Heavy modifiers: They come through appositional noun phrases, nonrestrictive relative clauses or preposed adjectival constructions. Sport Com.(s) regularly use these constructions to describe the athlete’s based on his background, his performance and other facts that are worth mentioning (ibid.: 163). Such constructions are used spontaneously without training and few people are able to use them in this way. These are also pointed out as markers of the register. For example, here is the French forward, Lowi Saha.

5- Tense usage: Simple present tense is used if the game is dominated by short actions, but if the Com. has to comment on an event that takes long time, present progressive is the choice, for example: Fowler showing great skill (ibid.: 164).

6- Linguistic routines: They are formulaic expressions or stretches of texts that are used repeatedly. This reflects the lack of creativity and due to the general human tendency to adopt formulas and routines, for example: getting through on the inside (ibid.: 169).

1.1. Sport Scripts

One characteristic of sport commentary as unplanned speech is “lacks forethought and organizational preparation” (Ochs, 1979: 55, cited in Delin, 2000: 42). By this feature it contrasts planned discourse where speech is designed before its expression. Therefore, sports commentary has the same characteristics of casual conversation in which both of them are unplanned speech (ibid.) In football, no script for the Com.(s) are to be ready for them to read and to be prepared before the game, as the actors do, because football commentary has no fixed structures (Television Football Commentary: online). Therefore, football Com.(s) have to memorize all eleven starting players’ names with the five substitutes, the names of the referees, the coaches, the line monitors and so on.

1.2. Sport Commentaries

Crystal and Davy (1969: 125) give a general understanding of the word ‘commentary’. They define it as “a spoken account of events which are actually taking place,” and, in the same meaning, they say that “it becomes obvious that the term ‘commentary’ has to serve for many kinds of linguistic activity, all of which would need to be represented in any adequate descriptive treatment, and would presumably require separate labels such as ‘exegesis’, political comment’, and so on” (ibid.). This definition has rather broad limitations in a way that it can suit different linguistic activities. The one who limits this definition and adopts it to make it fit for the sport commentaries is Ferguson. Ferguson (1983: 150) describes sport commentary as an oral speech of a continuous sport activity delivered to “unknown, unseen, heterogeneous audience” (ibid.). He uses the term ‘Colour Commentary’ (henceforth CC) in his definition of the sport commentary. He looks at this linguistic characteristic as vital and cannot be omitted for the following reasons:

- First and foremost, sport commentary is a “monolog or a dialog-on-stage” directed towards “unknown, unseen, heterogeneous audience” (ibid.). This type of audience listens to this commentary voluntarily even though they do not show their reaction to Com. though they are considered as clear partakers in the discourse.

- The Com.’s duty is not easy since, for instance football, is a fast sport. He has to provide the audience with on-the-spot information about what is happening in correspondence with the actual events that are happening in real time.

- In agreement with Ferguson (ibid.), Chovance (2009,1855) says that there are moments in the game that lack actions which need more skilful Com.(s) who have the ability of flow of speech to fill these moments often with description of “quite extensive narrative stretches” , in order to provide relevant information about the game or some background information about, for instance, the players, the previous similar games, the weather, the audience, etc. or opinions relevant to the match apart from heated actions.

Crystal and Davy (1969: 130) consider the “description of an activity and the provision of background information have been signaled out as centrally important parts” of the Com.’s job. They (ibid.: 150) mention that sport commentary has to provide further language requirements which make this kind of job significantly more demanding job. Examples of these requirements, the Com. has to produce rapid sentences at the time that he has no prefabricated sentences and phrases, which might be ready made or memorized from certain texts and references, to help them deal with the on-going events. This skill and language ability is strongly needed and developed by the Com.. It is called by Rowe (2004: 119) the ability to “improvise.” Consequently, the sport Com.(s) “are almost exclusively skilled professionals who can effectively deal with extreme situations” (ibid.).

The football Com.(s), in particular, insert clipped syllables which are articulated with more speed than usual for the purpose of emphasis and to indicate important events (Crystal and Davy, 1969:154). They consider that the main challenge for the sport Com.(s) in live sports coverage, for instance, is to create sense of being in the studio in spite of the distance between them and the audience. They also add that though there is no verbal or nonverbal interaction between the home viewers and the Com. but the latter has to address the viewers in a clear and informative way (Gruneau, 1989:134).

However, sports commentary is different from other conversational interaction such as political debates, sermons and lectures because the Com.(s) neither direct their speech to a specific person nor receive visual feedback from the audience (Beard, 1998: 79). Furthermore, Beard points out that sport commentary is “an instant response to something happening at the moment” and as “unscripted, spontaneous talk, aiming to capture the on-going excitement of the event” and this type of definition applies to live action commentary, that’s why sport commentary “is even more complex because it has to report simultaneously what is seen with the eye” at the time (ibid.: 62).

Further aspects of complexities are identified by Wilson (2000: 136) when he refers to the absence of turn taking, overlapping or backchannel in this type of interaction evidently. For that reason, sport commentary is viewed as the most complex kind of language activity due to the absence of verbal interaction between the Com.(s) and the audience who are unknown in the number for the addresser (the Com.).

The Com.(s)’ job is a demanding one. They have to learn the characteristics, techniques and principles of sport commentaries which help them in designing their speech. These skills are developed by time. They need long time of experience and practice to build such qualification and skills of speech. They may spend many years just to listen to the spoken words of professional Com.(s) in order to know how they use their special techniques to amuse audience. In addition, they will get many important characteristics of commentaries and develop them by their own way. However each Com. has his own way in commenting on sport game (Haynes, 2009: 25).

It is worth mentioning here that there are certain differences and similarities between commentaries on television and those on radio, due to different characteristics and strategies that are used by Com.(s) in describing the ongoing events. If you are listening to a football match on the radio, you will not be able to see what is happening. Therefore, the Com.(s) have to recreate the events in their own way to create sufficient image in the head of their audience. This means that they have to provide full information about what is happening during the football game without omitting any important thing, whereas televised football commentary, represents a type of monologic discourse in which there is no verbal or nonverbal interaction between the audience and the Com.(s) (Wilson, 2000: 136). However, in some matches, a number of Com.(s) interact with each other and take turns which makes the speech inapplicable to monologue (Ahmed, 2006: 9). According to Wilson (2000: 136), the speech is uncomplicated when there is direct interaction between at least two participants: the addresser and the addressee who can hear the speaker and easily respond whereas the exchanges will be more complex when there are more than two participants in indirect interaction.

In the televised commentary, unlike radio commentary, the audience have an available image of those events therefore the sport Com.(s) may employ ellipsis (Vierkant 2008:123). Moreover, the radio Com.(s) have to avoid silence as much as they can and try to pause only when they want to take a breath (Humpolík 2014:18-19). TV sport Com.(s), on the other hand, speak less because they do not need to comment on everything and they try to “paint word pictures” i.e. let the pictures speak for themselves (Beard, 1998: 64), as a result, more pauses are found in the televised commentaries as the Com.(s) find that it is not necessary to spend their time in commenting on every single detail that is happening as they do in the radio commentaries (ibid.: 59), therefore the differences in text type of the language of sport depend on the medium – television commentaries or radio commentaries (Taborek, 2012:238). However in both media the Com.(s) have the same purpose and the linguistic activity.

1.3. Commentary Styles

Crystal (2008:460) defines ‘style’ as “a technical linguistic term” used in everyday life interaction to refer to the way of speaking the speaker uses in order to achieve particular purposes. It is used to distinguish between the varieties of language by different individuals and social groups in their use of language. Therefore, the Com.(s), during doing their job, have to know when to use the proper style during different phases of the football game whether during play-by-play description (which is the same of play-by-play commentary phase) or during CC (Holmes, 1992: 277). The first kind of commentary which is play-by-play commentary (henceforth PPC) is used during the live action in which the Com.(s) use to clarify the facts of play that have occurred at that moment and they often speak more and fast, whereas the second one which is called CC is a term for “the more discursive and leisurely speech with which Com.(s) fill in the often quite long spaces between spurts of action” (ibid.). According to Beard (1998: 77), the Com.(s) use CC commentary style in evaluation or in their tactical analysis with rare overlaps and which contains additional information about the team, coaches, setting, or the individual players in order to fill the gaps during the action of the match. Therefore the Com.(s) have to know their responsibilities and to be careful in their speech (Balzer-Siber, 2015: online). Also it is necessary for the football Com.(s) to know when to shift from PPC to add additional information of CC within the same unit of commentary or vice versa (Ahmed, 2006: 6). Therefore the Com.(s) have to respond to what they see on the screen before completing their comments between language and pictures which results in shifting from one style to another (Beard, 1998: 74). Beard points out that there is another style is used by football Com.(s) which they call it “action replay commentary” (henceforth ARC) in which the Com.(s) use it when, for instance, a certain action in the match is repeated in slow motion or paused during the breaks in order to clarify a specific action for the audience (for example, how the player scores the goal) from different camera angles (ibid.). However ARC should not be considered either PPC because the action is already happened, or CC because there is no additional information that the Com.(s) use (Ahmed, 2006: 7-8). Therefore replay action should be seen as a third commentary style that is used to give a second description for the action (ibid.).

The analysis of the language of amusement in this study will depend on these three styles of commentaries which are used by the Com.(s) and how they utilize certain language devices to achieve amusement in each phase of these three types of styles.

2. The Pragmatic Perspective of Hyperbole

Alm-Arvius (2003: 135) mentions that exaggeration is very common in language as the term ‘hyperbole’ refers to such a kind of figurative language and falls within McQuarrie and Mick’s (1996:426) classification of figures of speech under the rubric of ‘tropes’. Synonymally, sometimes it is referred to as ‘overstatement.’ Originally, the reason for using this kind of tropes is of course rhetorical functions, i.e., “to make people really listen and remember the message” (Alm-Arvius, 2003: 136), especially the novel exaggeration that moves and amuses people. It lends people a “strong pragmatic force” (ibid.) than the literal meaning.

Arnold (1986: 65, cited in Mesz, 2014:33) refers to hyperbole as a rhetorical change in the statement to be an exaggeration tool by which the speaker expresses him/herself in “an intense emotional attitude towards the hearer.” He further classifies this rhetorical device in ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ connotation and ‘poetic’ and ‘linguistic’ hyperbole. The difference between the latter is that in poetry, hyperbole lies in the fact the it “creates an image,” whereas in linguistic hyperbole, “the denotative meaning quickly fades out and the corresponding exaggeration words serve only as general signs of emotion without specifying the emotion itself” (ibid.: 69).

Hyperbole is regularly and widely used in sport commentaries in certain moments of excitement, for instance, when making an amazing shoot and an overreaction of a skilful move: examples of hyperbole are: it is something amazing; a great move in sport, an underrated team beat a favourite opponent in a playoff series, a disappointing player

By using such pragmatic device the result will be violation of Grice maxims. This pragmatic strategy is necessarily needed to achieve amusement in the Com.(s)’ speech and to make their commentaries pragmatically are achieved.

One may ask about hyperbole, is not in the pragmatic domain. The answer is that the selection of this device is done on the basis of McQuarrie and Mick’s (1996: 426) classification. They classify rhetorical figures of speech into schemes and tropes. Schemes include sub classification of repetition and reversal while tropes’ sub classification is substitution and destabilization which fall under the rubric of pragmatics. Substitution consists of: hyperbole, ellipsis, epanorthosis, rhetorical question and metonym while destabilization includes: metaphor, pun, irony, and paradox.

3.1 The Speech Act Theory and Hyperbole

As far as speech act is concerned, hyperbole in sport commentaries is achieved by speech act of assertives (stating) which is followed by Searle’s classifications of speech and these acts are relevant to sport language and more particularly to football which are chosen in the present study to be representative for the English and Arabic football commentaries.

3.2 Gricean Maxims and Hyperbole

One of the most significant contributions to pragmatics is that of Paul Grice’s theory of implicature. According to Grice (1975:44-7), conversational implicature plays a significant role in speech. In conversation, people’s speech is usually understood even when they do not express their intentions directly because the hearer prospects that utterances should have certain principles. The CP comprises four basic rules. These rules are termed as conversational maxims and are briefly explicated as follows:

Quantity Maxim asks communicators to make their contribution as informative as is required for the recent purposes of the exchange; and not to make their contribution more informative than is necessary.

Quality Maxim requires saying what is true and avoiding that for which a tolerable evidence is lacked.

Relevance Maxim asks communicators to make their contribution as relevant as possible.

Manner Maxim asks communicators to be brief, orderly; and avoid ambiguity and obscurity of expression.

As far as the hyperbole is concerned, relevance maxim and quantity maxim are going to be violated by using exaggerating utterances by both of the English and Arabic the commentators.

The present study is going to show how and to which extent the exaggerated utterances which are used in the data of the study violate Grice’s maxims.

3.3. The Pragmatic Function of Hyperbole

The functions behind which the exaggeration language being used can vary in each occurrence in accordance with the purpose of the speaker himself. Thus, it is possible to draw some functions for exaggeration in its various devices. This function is as the following:

3.3.1. Emphasis is the main and the most common function of exaggeration. Exaggerating an utterance for emphasizing is a way that is so common and in a live use among people in general. The amount of contrast that exists between literal and exaggerated expression will determine how strong an interpretation is chosen. That is, the greater the contrast, the greater the emphasis or intensity of the utterance will be. The contrast thus carries the attitudinal content of the message (Fogelin, 1988:13).

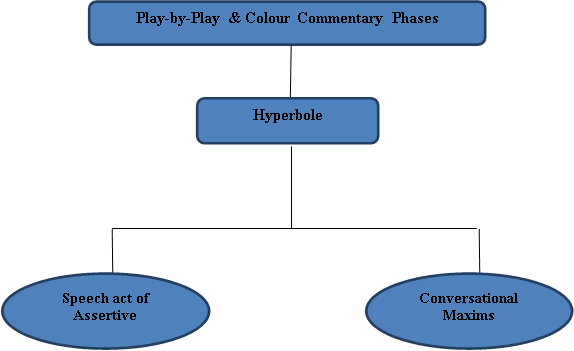

4. The Model of the Analysis

Putting together all the theories discussed above results in an eclectic model. This model is based on borrowing some ideas and terms from different theories which have been discussed earlier. In addition to certain modifications and observations made by the researcher himself.

The analysis will be done throughout the three phases of commentaries: these phases are: PPC, and CC. Each phase is different from the other and its own pragmatic strategies.

Figure (1) An Electric Model for the Analysis of English and Arabic Football Commentaries

5. Data Analysis and Discussions

Before analyzing the data, it is worth mentioning that due to the limits of this study, three English and three Arabic exaggerated commentaries are chosen for the purpose of testing the workability of the model developed by this study. The Arabic extracts are going to be translated by the researcher to be analysed in English language.

English Commentators Mark Tyler, Ray Hudson and Arlo White

Text 1:

“Messy, oh my God, oh my God, just when you think he’s done everything, he comes up with something even more special to catch Alison out and to make it three nil. The fans are worshiping him and you can understand why he is the God of the game.”

Phase: colour commentary

Speech act: assertives

Hyperbole: emphasis

Grice’s maxims: quantity and relevance

In the above text, the com. exaggerated the description of Messy and the goal by saying that he is a God and the fans are worshipping him. The function of is exaggeration is to emphasize the great performance of Messy.

The maxims of quantity and relevance are violated, in the sense that the com. Sais more than required and something irrelevant to football match which is worshipping.

Text 2:

“And here he is again, it’s astonishing, that is absolutely world class. No football team makes you feel like this. That is incredible and the saving is impossible.”

Phase: colour commentary

Speech act: assertive

Hyperbole: emphasis

Grice’s Maxims: quantity

The com. In the above text gives a statement about the goal and Messi he also exaggerated the description of the goal and the player again the function of the exaggeration here is to emphasize the performance of the player and the beauty of the goal. The quantity maxim is violated because the com. Mentions something which is rather more than required.

Text 3:

“He is brilliant I think we all need a cold shower afterward, Messy gets there first, still messy…oh what a goal absolutely stunning and magnificent goal from Lionel Messi.”

Phase: play-by-play

Speech act: Assertives

Hyperbole: emphasis

Crice’s maxim: quantity

The Com. states that the goal is incredible and Messi is a brilliant player.

The maxim of quantity is violated here by saying more than required to show to the audience the significance of the goal. The function of hyperbole is for emphatic purpose.

Arab commentators: Isam Al-Shawali , Ali Saeed Al-Ka’abi and Ra’ouf Khlef

Text 1:

“تمشي الكرة، شاهي ان يفرج العالم على هذه المكينة. تمشي الكرة ممتازة جدا عشر تمريرات وميسي يدخل يحط كرة مش معقول لا لا لا. خلص ماعادش علق اعتزلت ايها الجزيرة الرياضية باي باي انتهى الموضوع انتهت الحكاية اعتزلت التعليق. اشكرك ايتها الظروف التي جعلت من ليونيل ميسي لاعب. اشكر الظروف التي جعلت منك لاعب يا ميسي.”

” The ball goes, he wants to show his machine to the world. The ball goes again, very excellent, ten passes and Messi enters, puts the ball, unbelievable, no no no, that’s it I don’t want to comment any more I quit Al-Jazerra Al-Riyadhia bye bye it’s over the story is over, I will retire from my job. I thank the circumstance for making Lionel Messi a player.

Phase: colour commentary

Speech act: assertives

Hyperbole: emphasis

Grice’s maxim: quantity

The Arab Com. in the text above it too astonished by the performance of the player I the sense that he wants to quit his job and exaggerating the goal. The quantity maxim is violated here because he mentions things that are not required to emphasize the entertainment of the match.

Text 2:

هذا المرور معتاد هذا ميسي هذا ميسي الله الله الله الله. يا اخي انت عندك ميسي تصنع العجائب. والله ما في مثلك احد اي والله ما يجي مثلك احد وما في مثلك احد. عينك على ميسي عينك على ميسي عينك على المرور وبعد ذلك … الله الله الله خلاص تكون الامور انتهت يفعل ما يحلو له يقدم لكرة القدم شي اقرب الى الخيال.

“This pass is usual, this is Messi, this is Messi, oh my God, oh my God, oh my God. When you have Messi you make the miracles. I swear to God that there is no one like you and there is no one plays like you. Watch him and watch his passes. Afterwards… oh my God oh my God oh my God that’s it everything is over, he does what he desires, he makes things closer to the imagination.”

Phase: Colour commentary

Speech act: assertives

Hyperbole: emphasis

Grice’s maxims: quantity

In the above extract the Com. is too exaggerating the performance of the player by swearing that he is the unique player in the world. His purpose of violating the quantity maxim and saying more than required is to achieve the purpose of emphasis.

Text 3:

ليو ميسي بعكس الهجوم، برشلونة في وضعية هجومية رائعة وبيدرررو گووووووووول . لما ليو ميسي يتحرك هو الكبير هو القدير شوف الكورة شوف الصورة حتى الكامرات تستمتع بليو ميسي”.

“Lio Messi leads the counter-attack, Barcelona in a wonderful attack position, and Pedro, Goallllllllll. When Lio Messi moves, he is the great, he is the almighty. Look at the ball, look at the picture, even the cameras enjoy with Lio Messi.”

Phase: play-by-play

Speech act: assertives

Hyperbole: emphasis

Grice’s maxim: quantity and relevance

In the above phase of commentary the Com. describes the player as the “Almighty” which is hardly used to describe human beings. What is more, he mentions the cameras by saying that even the cameras enjoy the performance of the player which is also considered as a hyperbolic expression and all these expressions lead to violting the maxims of relevance and quantity.

The Discussion of the Analysis

We have noticed that hyperbole is clearly manifested in English and Arabic football commentaries and it is heavily used by the Coms. in colour commentary phase more than play-by-play commentary phase by both English and Arabic Coms. However, Arabic Coms. tend to exaggerate their comments on the players and the goals more than English Coms. do. Furthermore, the most utilized function of hyperbole here is the “Emphasis” function. As for the maxims, the most violated maxim in both English and Arabic commentaries is the quantity maxim. As far as speech act is concerned, speech act of assertives (stating) is almost always the highly frequent one that is used among other types of speech acts, because the Coms. tend to state and describe the events of the match to the audience.

Bibliography

Ahmed, H. A. (2006) A Contrastive Analysis of The Language of Sports Commentary on Televised Football Matches In Egyptian Arabic And British English: Unpublished Master thesis, Cairo University: Egypt, Giza.

Alm-Arvius, Christina. (2003) Figures of Speech. Lund: Student literature.

Arnold, I. V. (1986) The English Word. Moscow: VysSaja Skola.

Beard, Adrian (1998) The Language of Sport. London: Routledge.

Crystal, D. (2008) A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (Sixth Edition).

London: Blackwell Publishing

Crystal, David and Derek, Davy (1969) Investigating English Style. London: Longman.

Delin, Judy. (2000) The Language of Everyday Life: An Introduction. London: SAGE publication.

Ferguson, Charles A. (1983) ‘Sports announcer talk: Syntactic aspects of register variation.’ In Huebner, Thom (ed.) Sociolinguistic perspectives: papers on language in society, 1959 – 1994. New York, NY: 1996, Oxford University Press, pp.148-166.

Grice, H.P. (1975). Logic and Conversation. In P. Cole & J.I. Morgan (Eds.).Speech Acts. New York: New York Academic Press.

Gruneau, R. (1989) ‘Making spectacle: A case study in television sports

production.’ In Wenner, L.A. (Ed.) Media, sports, & society, pp. 134-154. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Haynes, R. (2009) ‘Lobby and the Formative Years of Radio Sports Commentary, 1935–1952’, Sport in History, 29, pp. 25–48.

Humpolík, R. (2014) Language of Football Commentators: An Analysis of Live English Football Commentary and its Types, Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis, Masaryk University, Faculty of Arts.

McQuarrie, Edward and David G. Mick (1996) ‘Figures of Rhetoric in Advertising Language.’ The Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (4), pp. 424-438.

Ochs, Elinor. (1979) Planned and unplanned discourse. In Talmy Givon, ed., Syntax and semantics, (12), Discourse and syntax, pp. 51-80. New York: Academic Press.

Sperber, Dan and Wilson, Deirdre (1995) Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Spurr, B. (2001) ‘The Language of Sport’ In Memoriam Bernard Kilgour

Martin.

Taborek, Janusz (2012) The language of sport: Some remarks on the

language of football. Research Gate: Adam Mickiewicz University

Vierkant, Stephan (2008) ‘Metaphor and live radio football commentary.’ In Lavric, Eva, Gerhard Pisek, Andrew Skinner and Wolfgang Stadler (eds.) The Linguistics of Football. Tübingen: Gunter Narr, pp. 121-132.

The Arabic Extracts are taken from the bellow YouTube URL accessed on 9/12/2021

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1NZkQWIddKU

The English Extracts are taken frombellow YouTube URL accessed on 9/12/2021

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1NZkQWIddKU