Dr. Yousif Abdelrahim1

Department of Management, College of Business Administration, Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University

Email: yabdelrahim@pmu.edu.sa

HNSJ, 2023, 4(2); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj42106

Published at 01/02/2023 Accepted at 21/01/2023

Abstract

The study aims to use Hedonism and Social Identity theories to explain why Sudanese people use Wasta in excess. The authors empirically investigate the connection between corruption in Sudan and Wasta, a social network of interpersonal relations implanted in lineage, tribe, family, and extended connections. Utilizing the Structural Equation Modeling technique, the authors examined the three hypotheses by collecting primary data (N=410) from male and female private sector employees in Sudan via Google Survey Link. Wasta and corruption have a positive and significant relationship, according to the study’s results. The findings also conclude that, out of the three Wasta components (Mojamala, Hamola, and Somah), Hamola and Somah are the most influential Wasta factors that drive corruption. The findings validate the three Wasta dimensions and help researchers utilize a Wasta conceptual framework for the link between Wasta and corruption. International investors may be capable of coping, thriving, and prospering in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) without disregarding their regulations of business ethics if practitioners apprehend the concept of Wasta. Also, foreign enterprises doing business in Sudan and the MENA profit from having a concrete familiarity with Wasta because it makes them conscious of the overlooked needle of Wasta, encourages them to endure proactive measures and lessens the likelihood of bribery. In addition, apprehending Wasta would inspire multinational corporations to prioritize the development of practicum programs that prepare global assignees about the significance of cultural norms, and values. And how business firms in the MENA are influenced by national culture.

Key Words: Wasta; Corruption; Mojamala; Somah; Hamola

Introduction

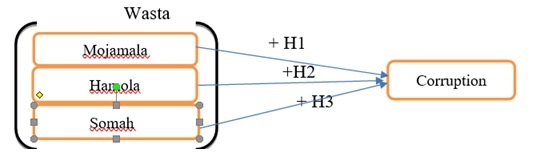

According to Bishara (2011), bribery, kickbacks, favoritism, and Wasta—interpersonal and social network relationships implanted in a family, clan, tribe, and extended connections (Smith et al.,2012, Muna, 1980) are widely spread in the MENA region. The MENA region ranked poorly when it comes to corruption and business ethics. According to Cunningham and Sarayrah (1993, 1994), Wasta is associated with personal relationships and social connections in the MENA. There are three distinct ways that Wasta is practiced in the MENA region: According to Berger et al., (2015), Mojamala (the sensation of commitment and passionate wisdom), Hamola (the degree to which a person under a moral obligation to give someone back a favor), and Somah (an individual’s prominence and credibility in a society (Berger et al, 2015). Wasta is acknowledged as an element that lessens equal chances for workers and businesses (Mohamed and Mohamad, 2011). Wasta is linked to favoritism (Alenezi, Hassan, Abdelrahim, & Albadry, 2023), and corruption, and both of these factors are influenced by Wasta. Wasta eradicates social and trade equality by propagating the idea that employees and business firms have different opportunities, and it also influences corruption in three ways: gifts, favors, and accepting bribes. When doing business in the MENA, and Sudan in particular, Wasta remains a problem for Western companies. Wasta has been witnessed to have unfavorable consequences on worker morale and perceived competency (Mohamed & Mohamad, 2011). According to Al-Enzi (2017), Wasta’s deep rootedness in Kuwait, for instance, has a damaging influence on worker dedication, organizational invention, and human resource leadership rules. As a result, Wasta and corruption in the MENA region must be investigated. Sudan was chosen by the authors because Transparency International has listed Sudan among the top ten most corrupt countries over the past decade. Wasta and corruption have not been linked in previous empirical studies (Smith et al.,2012; According to Sudani and Thornberry (2013), but there is a lot of evidence that the two ought to have a conceptual connection (Kilani and Sakijha, 2002;(2006) (Hutchings and Weir). This argument is supported by theoretical connections between Wasta and corruption. However, despite the strong conceptual connections between Wasta and corruption, no empirical examinations of this association have been conducted. Therefore, by empirically investigating the link between Wasta and corruption, the goal of this study is to fill the aforementioned gap in the published literature (fig. 1). Two research questions arise when examining the connection between Wasta and corruption and incorporating the dark side of Wasta into the existing Arab Business Model. First, what is Wasta’s role in Sudan’s corruption? Second, what connection does Wasta have to corruption? By empirically investigating the connection between Wasta and corruption and validating the Wasta three constructs, this study makes significant theoretical contributions. Additionally, the findings of this study have practical repercussions for multinational corporations seeking a deeper comprehension of Wasta in Sudan and the MENA region. When conducting business in Sudan, in particular, and the MENA region, as a whole, multinational corporation may be able to avoid legal issues and hire the appropriate managers.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development:

Fig. (1): The Conceptual Framework for the Relationship between Wasta and Corruption

Corruption

Transparency International (TI) defines corruption as the misuse of authority for personal gain. According to Warf (2015), corruption is a behavior that is widespread throughout the MENA region and deeply rooted in the region, and Sudan is no exception. Political systems and cultural norms have an impact on corruption in the MENA region (Shaibi, 1999, October). And society is divided into three groups by corruption: those who steal bribes, those who give favors, and those who are denied favors and made to pay bribes (Sapsford, Tsourapas, Abbott, and Teti, 2017). Wasta is related to corruption because it is a major and obvious breach of trust in employment, government, and business (Luo, 2008) (Sapsford et al.).2017). Additionally, Wasta is associated with corruption due to its emphasis on reciprocity and gift-giving. According to Smith (2001), researchers ought to comprehend corruption within the context of social networks, kinship relationships, and other social ties. According to Safina (2015), researchers have established a link between corruption and favoritism because the favored individual would question the reciprocity of gifts or other forms of favors.

Wasta

Researchers have defined Wasta in different ways. Nevertheless, there is one thing that unites all Wasta definitions: Wasta is based on the social unit of the family (Rice, 2004). In Arab nations and communities, families serve as the center of society and serve as its foundation (Barakat, 1993). According to Gesteland (2005), the Arab World is a relation-oriented society that places a greater emphasis on building and supporting connections within the business instead of straight closing a contract. This is true regardless of family affiliation. According to Cunningham & Sarayrah (1993, 1994), the MENA concept of Wasta is linked to social connections and Wasta impacts decision-making in business settings.

Wasta is influenced by elements of national culture like collectivism (Aldossari & Robertson, 2014). Wasta is connected to collectivism and power distance, according to Dunning and Kim (2007). For instance, Arab culture promotes the use of Wasta as an instrument of acquiring admission to high-ranking members of society due to power distance, or unequal power distribution (Hutchings & Weir, 2006b). Wasta too is linked to harmony, which is prized in collectivist cultures of the MENA region; According to Matsumoto (2000), people are more likely to engage in activities that promote harmony and avoid those that jeopardize harmony. According to Hutchings and Weir (2006b), uncertainty avoidance may play a significant role in how to handle family members, friends, strictly known individuals, or strangers. Yahchouchi (2009) claims that Lebanese national culture nurtures relations-oriented administration in business instead of task-oriented administration, demonstrating the impact of nationwide culture on Wasta. According to Barnett et al. (2013), Wasta is practiced in the MENA because it holds a sense of satisfaction, gratification, fulfillment, and reputation, which drives those who practice it happy. Bentham’s (1996) hedonism theory explains these feelings and the absence of pain associated with Wasta use. According to the theory, people should strive for happiness and steer clear of suffering or unhappiness. As a result, Wasta is practiced by a lot of people in the MENA region to find happiness. Those who ask for Wasta and those who do their jobs for them share the happiness and pleasure caused by Wasta. as a type of social capital, Wasta (Routledge & von Amsberg, 2003) enables individuals to utilize their social power by networking to overcome business challenges (Hutchings & Weir, 2006b; Xin & Pearce, 1996).

Wasta’s mission has evolved from intermediary purposes (i.e., assisting in the resolution of the conflict between groups) to intercessory purposes (i.e., assisting unqualified individuals in earning money or obtaining employment, promotion, or other benefits). Al Suleimany (2009) says that intercessory. Wasta has made it possible for wrongdoing and corruption (such as favors, gifts, and kickbacks).2008 (Wunderle). Matsumoto (2000) says that Wasta lets people use their connections to pursue their personal interests. According to Hutchings & Weir (2006b), Wasta is associated with gift-giving, favor-exchange, and the expectation of mutuality in the future.

Wasta is considered corruption (Luo, 2008) because it is a prominent and obvious breach of trust in employment, business, and the civil service (Sapsford, Tsourapas, Abbott, & Teti, 2017). People in the MENA who don’t have Wasta contacts from their household, tribe, or close ones are forced by reality to look for individuals who can assist them get a job or get the services they need for money. Wasta has links to corruption because it promotes bribery through gifts and other illegal acts. As a result, the authors of this study contend that Wasta, in its three distinct forms—Homola, Mojamala, and Somah—is associated with corruption.

WASTA Dimensions Versus Corruption

Mojamala and Corruption

According to Berger et al. (2015), Mojamala is the sensation of devotion and passionate familiarity with the other group, when a person shows their level of cultural understanding to the other person by not worrying them due to a firm sense of devotion, whether in trade, social, or feast settings. According to El-Said and Harigan (2009), in MENA culture, it is inconceivable to commence a meeting or other noteworthy business dealings without coffee traditions because of the standards and values specified by Mojamala. Sudanese businesspeople enjoy talking frankly about business deals and interact with one another repeatedly, which helps them deal with uncertainty and troubles. According to Al-Omari (2003), Mojamala is one path Arabs portray in their readiness to accommodate harmony and bypass disputes in business negotiations. All guests are required to drink tea or coffee during the rituals because they comprehend Mojamala’s feelings for the host. According to Sudanese norms, guests are aware that declining to do so will annoy the host and defy Arab values and practices. As a result, Mojamala makes Arab societies save face. According to Velez-Calle, Robledo-Ardila, and Rodriguez-Rios (2015), face-saving is essential not solely for the household and tribe members but also the vast networks. People in Arab communities consider Mojamala as a social power that holds a relationship between two groups via an individual’s generosity, readiness to support, and face-saving to make other individuals delighted with the someone who delivers Mojamala. Consequently, regardless of the price of favoritism, individuals do not like to bother others (Berger et al.,2015) because individuals would think about the reference individual’s feelings before making a substantial decision. Mojamala is associated with favoritism in the MENA region (Berger et al.,2015), as interpersonal interactions and significant emotional feelings are the foundation of business relationships in Arab societies (Khakhar and Rammal, 2013). People favor one person to save face because of Mojamala’s strong emotions. Favoritism leads to corruption, according to Akbari, M., Bahrami-Rad, and Kimbrough (2016). Sawalha (2002) came to the conclusion that favoritism is corruption. Corruption is caused by favoritism because the favored individual endeavors to bribe someone who favored him or her indirectly by giving gifts or returning favors like jobs, promotions, or signing a contract to show how much they care. In addition, favoritism encourages corruption (Safina, 2015), as the favored individual may reconsider giving gifts in return for favors.

In the MENA, the beginning of a business meeting is marked by the host’s generous offering of free meals, drinks, and gifts. Prior to a company meeting, a company manager who masters social relations and emotional understanding of the host would be more likely to obtain the best deal (Berger et al.,2015). As a result, Mojamala encourages favoritism, which is a form of corruption based on mutual trust and favoritism (Lowe et al.,2008). As a result, the authors contend that Mojamala fosters corruption. The authors propose hypothesis 1 (H1) in light of the preceding discussion:

H1: Corruption in Sudan is partially caused by the high levels of Mojamala brought on by cultural and emotional factors.

HAMOLA

The level of mortal compassion, kindness—the capacity to comprehend and disseminate the emotions of another person—and favoritism—giving or receiving favors from family members, tribesmen, friends, or others—are all examples of Hamola. To put it another way, Hamola is the degree to which someone else is owed favors. According to Berger et al., (2015), Hamola is regarded as Wasta’s companion element. It determines how an individual respond to feelings and emotions. In Hamola, empathy is the capacity to comprehend and candidly express another person’s feelings. The key to thinking about repaying favors and freeing oneself from being owed is the sense of owing someone or someone else owed to you something. In Sudan, people who return favors do so to free themselves from obligations to other members of their families or groups. According to Mohamed and Mohamed (2011), it is also believed that practicing Hamola helps people achieve positive outcomes in business interactions, reduces uncertainty, and creates value. According to El-Said & Harrgan (2009), Hamola harbors the importance of interaction and promotes reciprocity among individuals, allowing for the achievement of these beneficial business outcomes. According to El Said & Harrigan (2009), interchange among someone entails the exchange of favors and gifts, which is considered to be corruption. According to Abosag & Lee (2013), Hamola is linked to the giving of gifts, dining and drinking, and reciprocal help for those to whom the Wasta individual owes a favor. According to Rice (2004), a family is a foundation for job security and advancement in MENA society. Sudan is not an exception to Arab collectivist societies’ long-term and steadfast dedication to extended family and friends (Hofstede, 2006). People favor their families because of the pressure they feel to support one another and keep their jobs (Bian and Ang, 1997). People in the Middle East and North Africa consider favoritism toward a relative when it comes to hiring or securing a business deal to fulfill a Hamola obligation (Abu-Saad, 1998). As a result, Hamola encourages favoritism. According to Abosag & Lee (2013), a key to devotion and social grids, which are straight linked to the growth of business connections, is reciprocity. According to Cialdini (1993), reciprocation is a powerful behavioral impact that guides one to repay what another individual has given in the past.

Hamola tells company owners in Sudan to treat family members or groups of people in a particular way when offering a job or trade deals. Managers see this special treatment as a way to fulfill a responsibility imposed by Hamola. According to Al-Rasheed (1993), the practice of managers giving preferential treatment to members of a family or group is typically regarded as favoritism or nepotism in Western cultures. In business settings, it is considered favoritism to favor a relative (Hollenson, 2007). Hamola demands that the favorite reciprocates by giving the favorite a gift or a favor. As a result, Hamola leads to favoritism and gift giving, which in turn leads to corruption (Lowe et al.,2008). According to Huntings & Weir (2006) b, business activities in MENA societies spin around interpersonal relationships and social networks entrenched in clan and family relations that assess verbal commitments of agreed-upon agreements. According to Abosag and Lee (2013), the expansion of business connections in the MENA region is connected to exchange via the commitment to returning a favor. According to El Said & Harrigan (2009), Hamola reciprocity is the return of favors by the beneficiary or someone acting on their behalf in the business. Giving a gift, going out to eat and drink, or helping out when needed are all examples of ways to return favors (Abosag and Lee, 2013). In a business setting, giving gifts or favors is considered bribery. As a result, the authors contend that Hamola causes corruption. The authors propose hypothesis 2 (H2) in line with the preceding discussion:

H2: Corruption in Sudan is partially caused by the high levels of Hamola brought on by cultural and emotional factors.

SOMAH

Wasta’s cognitive component is Somah. Wasta is described as an individual’s prestige, readiness to present themselves professionally, and level of respect. Somah is a reflection of a person’s credibility and business relationships. According to Al-Kandari & Al-Hadban (2010), individuals and businesses typically evaluate Somah based on how well the other party keeps its verbal and written agreements. Somah is constructed on the tribe’s prestige, individual motions, and transferred history in Arab societies (Berger et al.,2015). Somah is settled in business around how long the two parties have been in mutual connections, how the business was run, and how disagreements between them have been resolved in the past. As a result, Somah involves businesses and individuals working together to uphold a positive reputation. Hence, Somah has a connection to relationships and the giving of gifts or favors. Exchanging favors or gifts in a business relationship is considered corruption because it is bribery.

In addition, according to Kabasakal & Bodur (2002), people in MENA societies typically define who they are with other members of their family, so the interests of the family come first. Family members in Sudan are willing to do favors for members of their in-groups, friends, and tribes because they want to appear kind, generous, and have a sound Somah (or prestige) for themselves and their extended families. According to Abdalla & Al-Homoud (2001), for instance, Saudi Arabian values and traditions demand that members of the immediate and extended families support one another and cooperate. Because individuals are required to meet tribal and family obligations that are dictated by societal worth and traditions, these values and norms favor extended family members in the community and institutions (Abdalla et al.,1998). Tajfel and Turner’s (1979) social identity theory states that people strive for a positive social identity (i.e., the best reputation). Everyone strives to improve their appearance and reputation. According to the theory, membership in a group creates an in-group, which is more likely to show favoritism toward the out-group. Sudani and Thornberry (2013) state that a person must favor their close ones or face the outcomes. According to Schain (2010), public employees in Jordan, for instance, prefer to bypass social separateness and bad prominence. As a result, Somah cultivates favoritism, which constitutes corruption (Lowe et al.,2008). As a result, the authors propose hypothesis 3 (H3) and argue that Somah is the cause of corruption:

H3: Corruption in Sudan is partially caused the high levels of Somah brought on by cultural and emotional factors.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sampling Population

Business managers, supervisors, and workers (300 men and 110 women) from all levels of the private sector in Sudan make up the survey’s sample. Probability random sampling was used to select respondents between the ages of 25 and 65. The authors used a link from a Google Survey, and 86% of people responded. By increasing the rate of responses, non-response bias was reduced. The authors took several steps to accomplish that. The authors first sent What’s up messages to prospective customers. Second, the authors conducted two follow-up calls with non-respondents. Thirdly, the survey was offered in both Arabic and English by the authors. Fourth, prior to sending the questionnaire, the authors announced via social media. The authors also provided respondents with options for a blended mode survey. For instance, respondents can respond by email or by clicking the What’s Up link. According to research (Ali, 1995), the majority of Arab business leaders share a number of basic matters that reflect tribal customs, which is why the authors chose Sudan to describe the MENA business leadership. Despite differences in economic, social, political, and organizational systems, Arabs in the MENA region share a cultural and racial identity (Hutching and Weir, 2006a). According to Kabaskal & Bedour (2002), Arabs also share social norms and business practices. Additionally, the Arab collective and tribal social system is the primary source of Wasta (Smith et al.,2012).

Measuring the Dependent Variable

The study’s dependent variable is corruption, which is defined as an act committed by a person involved in business transactions and is a crime in most jurisdictions. Abuse of power, extortion, cartels, money laundering, embezzlement, and favoring in exchange for personal acquisition are all examples of corruption. However, the study defines corruption as bribery, power abuse, gift-giving, and favor giving. The authors tested the dependent variable by linking corruption items from Transparency International (TI)’s 2006 Global Corruption Barometer via Google Survey. The focus of GCB is on gaining an understanding of bribery and political corruption in the public sector, mirroring the viewpoints of business leaders and experts. In the TI-commissioned survey on corruption, Gallup International surveyed 59,061 people in 114 countries about their recent experiences with bribery. In Sudan, respondents were also asked if they had paid bribes for any of six services—police, registry, medical, utilities, education, or legal/judiciary—in the previous year. In addition, respondents were asked if anyone in their contacts, friends, or family had given money to public officials, police officers, or civil servants, among other individuals, and for what reason. Last but not least, respondents were asked how important personal connections or relationships are for completing tasks. The survey uses a 5-Point Likert scale, with 1 representing strong agreement and 5 representing strong disagreement. Where “not at all,” “4 to a large extent,” and “no answer” is used.

Measuring the Independent Variables

Wasta is the individual-level independent variable measured in three dimensions; Mojamala, Hamola, and Somah all refer to feelings of loyalty and emotional understanding. Somah, on the other hand, refers to a person’s credibility and reputation. The Wasta survey uses a seven-point Likert scale, with 1 representing strong agreement and 7 representing strong disagreement. Seven items are used to evaluate Mojamala: Six items are used to evaluate Hamola: and there are seven measures for Somah. Berger et al. created the Wasta scale (2015) with a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.79

Data Analysis and Test Results

The authors used AMOS analysis to check the model fit before putting the study’s three hypotheses to the test (table 1). The model’s fit is demonstrated by the model fit indices.

Table (1): The indices of model fit

| Index | Index Value | Acceptable |

| GFI | .922 ≥ .90 | Yes |

| CFI | .904 ≥ .90 | Yes |

| NFI | .900 ≥ .90 | Yes |

| RMSEA | .070 between 0.05 to 0.08 | Yes |

| Chi-Square | 236.752 | Yes |

In addition, the authors used the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique to test the three hypotheses. The findings show that Hamola (b = 0.41, p-value = 0.000, < 0.0001, significant) and Somah (b = 0.269, p-value = 0.001, < 0.05, significant) are significantly related to corruption. However, Mojamala (b = 0.066, p-value = 0.251, > 0.05, not significantly) is not significantly related to related to corruption (table 2).

Table 2: Hypotheses Test Results Using SEM

| Relationship between Dimensions | p-value | p-value | Significance |

| Mojamala → Corruption | 0.066 | 0.251 | No |

| Hamola → Corruption | 0.269 | 0.001 | Yes |

| Somah → Corruption | 0.410 | 0.000 | Yes |

Discussion

The Theoretical and Practical Implications

The most likely causes of corruption in Sudanese society appear to be two of the three Wasta factors—Hamola and Somah—possibly because Sudanese people are concerned about a person’s reputation, willingness to behave well in society, and level of respect. Also, Sudanese people have a lot of empathy for people who think they need help or support. However, the findings demonstrate that Sudanese people value their reputation more than loyalty or saving face.

By validating the three Wasta dimensions and creating a Wasta conceptual framework for the connection between Wasta and corruption, the findings of this study add significantly to the body of knowledge. Foreign investors may be able to cope, succeed, and flourish in Western countries with

out breaking their codes of ethics or business laws if practitioners understand the concept of Wasta. Also, foreign companies doing business in the MENA benefit from having a solid understanding of Wasta because it makes them aware of the unseen hand of Wasta, enables them to take proactive or preventive measures and reduces the likelihood of bribery. In addition, comprehending Wasta would motivate multinational corporations to place a high priority on the development of training programs that teach international assignees about the significance of cultural norms and values. And how business in the MENA region is influenced by national culture.

Future Research

There are some limitations and flaws in this study. Only respondents from Sudan, a nation in the MENA region, were included in the survey. To determine whether the Wasta phenomenon and corruption are influenced by cultural differences and political systems, additional countries in the MENA region should be studied in future research. Also, age and education seem to have an effect on Wasta because older people with a lot of education tend to be warier of Wasta than younger people with less education. As a result, age and education should be controlled for in future research.

References

Abdalla, I. A., & Al‐Homoud, M. A. (2001). Exploring the implicit leadership theory in the Arabian Gulf States. Applied Psychology, 50(4), 506-531.

Abdalla, H. F., Maghrabi, A. S., & Raggad, B. G. (1998). Assessing the perceptions of human resource managers toward nepotism: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Manpower, 19(8), 554-570.

Abosag, I., & Lee, J.-W. (2013). The formation of trust and commitment in business relationships in the Middle East: Understanding Et-Moone relationships. International Business

Abu-Saad, I. (1998). Individualism and Islamic work beliefs. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29(2): 377–383. eview, 22: 602–614.

Akbari, M., Bahrami-Rad, D., & Kimbrough, E. O. (2016). Kinship, Fractionalization and Corruption.

Alenezi, M., Hassan, S., Abdelrahim, Y., & Albadry, O. (2023). Wasta and Favoritism: The Case of Kuwait. In International Conference on Business and Technology (pp. 705-716). Springer, Cham.

Al-Enzi, Abrar A. (2017): The influence of Wasta on employees and organisations in Kuwait: exploring the impact on human resource management, knowledge sharing, innovation and organisational commitment. Loughborough University. Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/32601

Aldossari, M., & Robertson, M. (2014). The Role of Wasta in Shaping the Psychological Contract: A Saudi Arabian Case Study. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2014, No. 1, p. 15447). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

Al-Kandari, Yagoub & Ibrahim Al-Hadban (2010). Tribalism, Sectarianism, and Democracy in Kuwaiti Culture. Domes: digest of Middle East studies. 19.10.1111/j.1949-3606.2010.00034. x.

Al Omari, J. (2003). The Arab Way: How to work more effectively with Arab culture. Oxford. How to Books, ltd.

Al-Rasheed, A. (1993). Manager motivation and job satisfaction: how do Jordanian Arab bank managers perceive the higher goals of the job? Paper presented in the first Arab Management Conference at Bradford University, UK, July 6–8.

Al Suleimany, M. (2009). Psychology of Arab Management Thinking: Arabian Management Series. Trafford Publishing. USA. ISBN 978146982705.

Barakat, H. (1993). The Arab world: Society, culture, and state: University of California Press.

Barnett, A., Yandle, B., & Naufal, G. (2013). Regulation, trust, and cronyism in Middle Eastern societies: The simple economics of “wasta”. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 44, 41-46.

Bentham, J. (1996). The collected works of Jeremy Bentham: An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press.

Berger, Ron & Silbiger, Avi & Herstein, Ram & Barnes, Bradley R., 2015. “Analyzing business-to-business relationships in an Arab context,” Journal of World Business, Elsevier, vol. 50(3), pages 454-464.

Bian, Y., & Ang, S. (1997), “Guanxi networks and job mobility in China and Singapore”, Social Forces, Vol 75, No 3, pp. 981-1007.

Bishara, N.-D. (2011). Governance and corruption constraints in the Middle East: Overcoming the business ethics glass ceiling. American Business Law Journal, 48(2): 227–283.

Cialdini, R. (1993). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Revised ed. New York: Quill.

Cunningham, R. B., & Sarayrah, Y. K. (1993). Wasta: The hidden force in Middle Eastern

society. Praeger Publishers.

Cunningham, R.B., & Sarayrah, Y.K. (1994), “Taming Wasta to Achieve Development”, Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol 16, No 3, pp. 29-39.

Dunning, J. H., & Kim, C. (2007). The cultural roots of guanxi: An exploratory study. World Economy, 30(2), 329–341.

El Said, H., & Harrigan, J. (2009). You reap what you plant: Social networks in the Arab world – The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. World Development, 37(7): 1235–1249.

Gesteland, R. (2005). Cross-cultural business behavior: Negotiating, selling, sourcing and managing across cultures (4th ed.). Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Hofstede, G. (2006). What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers’ minds versus respondents’ minds. Journal of international business studies, 37(6), 882-896.

Hollensen, S. (2007). Global marketing: a decision – oriented approach (4th ed.). London: Prentice Hall.

Hutchings, K., & Weir, D. (2006a). Guanxi and Wasta: a comparison. Thunderbird International Business Review, 48, 141-156.

Hutchings, K., & Weir, D. (2006b). Understanding networking in China and the Arab World: Lessons for international managers. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(4), 272-290.

Kabasakal, H., & Bodur, M. (2002). Arabic cluster: a bridge between East and West. Journal of World Business, 37(1), 40-54.

Khakyar, P., and Rammal, H. G. (2013). Culture and business networks: International business negotiations with Arab managers. International Business Review, 22(3), 578-590.

Kilani, S. and Sakijha, B. (2002), Wasta: The Declared Secret, Arab Archives Institute Amman, Jordan.

Loewe, M., Blume, J., & Speer, J.. (2008). How Favoritism Affects the Business Climate: Empirical Evidence from Jordan. Middle East Journal, 62(2), 259–276. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482509.

Luo, Y. (2008). The changing Chinese culture and business behavior: The perspective of intertwinement between guanxi and corruption. International Business Review, 7(2), 188–193.

Matsumoto, D. (2000). Culture and psychology, people around the world. Australia: Wadsworth Thomas Learning.

Mohamed, A. A., & Mohamad, M. S. (2011). The effect of wasta on perceived competence and morality in Egypt. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 18(4), 412-425.

Muna, F. (1980), The Arab Executive, St. Martins, New York.

Rice, G. (2004). Doing business in Saudi Arabia. Thunderbird International Business Review, 46(1), 59–84.

Sawalha, F. (2002), “Study says ‘wasta’ difficult to stamp out when advocates remain in power”,

Jordan Times, April 1.

Routlege, B. R., & von Amsberg, J. (2003). Social capital and growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 167–193.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Safina, D. (2015). Favouritism and nepotism in an organization: causes and effects. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 630-634.

Sapsford, R., Tsourapas, G., Abbott, P., & Teti, A. (2017). Corruption, trust, inclusion and cohesion in North Africa and the Middle East. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1-21.

Shuaibi, A. (1999, October). Elements of Corruption in the Middle East and North Africa the Palestinian Case. In the 9th International Anti-Corruption Conference, Durban, South Africa.

Smith, D. J. (2001). Kinship and corruption in contemporary Nigeria. Ethnos, 66(3), 344-364.

Smith, P., Torres, C., Leong, C.-H., Budhwar, P., Achoui, M., & Lebedeva, N.

(2012). Are indigenous approaches to achieving influence in business organizations dis- tinctive? A comparative study of Guanxi, Wasta, Jeitinho, Svyazi and Pulling Strings. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(2): 333–348.

Sudani, Y., & Thornberry, J. (2013). Nepotism in the Arab world: An institutional theory perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(1): 69–96.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Velez‐Calle, A., Robledo‐Ardila, C., & Rodriguez‐Rios, J. D. (2015). On the influence of interpersonal relations on business practices in Latin America: A comparison with the Chinese guanxi and the Arab Wasta. Thunderbird International Business Review, 57(4), 281-293.

Warf, B. (2015). Corruption in the Middle East and North Africa: A Geographic Perspective. The Arab World Geographer, 18(1-2), 1-18.

Wunderle, W. D. (2008). A manual for American servicemen in the Arab Middle East: Using cultural understanding to defeat adversaries and win the peace. New York: Skyhorse Pub.

Xin, K. R., & Pearce, J. L. (1996). Guanxi: Connections as subtitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1641–1658.

Yahchouchi, G. (2009). Employees’ perceptions of Lebanese managers’ leadership styles and organizational commitment. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 4(2), 127-140.