Yousuf Taresh Hilal Jabur Al Amaya1

University of Gezira, College of Arts and Human Sciences, Department of English, Sudan.

E-Mail: linguistyousuf1970@gmail.com

Supervisor: Professor Dr. Elhaj Ali Adam Esmaeil

E-Mail: Elhajadamali@gmail.com

HNSJ, 2023, 4(3); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj437

Published at 01/03/2023 Accepted at 05/02/2023

Abstract

The current study attempts to investigate Iraqi EFL college students’ productive ability in key terms used in the three main linguistic schools: Historical Linguistic School, Structural Linguistic School, and Transformational-Generative Linguistic School. It is worth mentioning that this study is restricted to the major linguistic terms used the three main linguistic schools that are of concern to the EFL college students in Iraq. As a matter of fact, these terms are associated with language use and usage as well, in consequence, they constitute a daunting challenge for all foreign students of English as James (1980) sustain. In this work, the linguistic terms at issue are classified into three types: historical linguistic terms, structural linguistic terms, and transformational-generative linguistic terms. After surveying such terms, the present study considers a questionnaire designed for a representative sample of (100) EFL students chosen randomly from the 4th year stage (academic year 2022-2023) in the Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Babylon with the purpose of examining those EFL learners’ productive ability in this respect.

Key Words: : EFL College Students, Linguistic Terms, Historical Linguistic School, structural Linguistic School, transformational-Generative Linguistic School, Productive Ability

عنوان البحث

القدرة الانتاجية لطلبة المستوى الجامعي الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المصطلحات الرئيسية المستخدمة في المدارس اللغوية الرئيسية

يوسف طارش هلال جبر العميه1

1 جامعة الجزيرة، كليّة الآداب و العلوم الإنسانية، قسم اللغة الإنجليزية، السودان.

بريد الكتروني: linguistyousuf1970@gmail.com

المشرف: البروفيسور الدكتور الحاج علي آدم إسماعيل / جامعة الجزيرة / كليّة الآداب

و العلوم الإنسانية / قسم اللغة الإنجليزية

البريد الإليكتروني: Elhajadamali@gmail.com

HNSJ, 2023, 4(3); https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj437

تاريخ النشر: 01/03/2023م تاريخ القبول: 05/02/2023م

المستخلص

تحاول الدراسة الحالية تقصي القدرة الانتاجية لدى طلبة المستوى الجامعي العراقيين الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في مصطلحات رئيسية مستخدمة في المدارس اللغوية الرئيسية الثلاثة: المدرسة اللغوية التاريخية, المدرسة اللغوية التركيبية, و المدرسة اللغوية التحويلية-التوليدية. و من الجدير بالذكر إن هذه الدراسة محددة بالمصطلحات اللغوية الرئيسية المستخدمة في المدراس اللغوية الرئيسية الثلاثة التي تشكل اهتمام طلبة المستوى الجامعي الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في العراق. و كمسالة حقيقية, إن هذه المصطلحات ترتبط مع استخدام و استعمال اللغة و كنتيجة لذلك فأنها تشكل تحدي خطير يواجه جميع طلبة اللغة الإنجليزية كما يؤكد جيمس (1980). في هذا العمل, فأن المصطلحات اللغوية المستهدفة هنا قد صنفّت الى ثلاثة أنواع: المصطلحات اللغوية التاريخية, المصطلحات اللغوية التركيبية, و المصطلحات اللغوية التحويلية – التوليدية. و بعد اجراء المسح لهذه المصطلحات, فأن الدراسة الحالية قد اعتمدت استبيانا لعينة تمثيلية تتكون من (100) طالب تم اختيارهم عشوائيا من المرحلة الرابعة للسنة الدراسية (2022- 2023), قسم اللغة الإنجليزية, كليّة التربية للعلوم الإنسانية, جامعة بابل لغرض فحص القدرة الانتاجية للطلبة الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في هذا المجال.

الكلمات المفتاحية: طلبة المستوى الجامعي الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية, المصطلحات اللغوية, المدرسة اللغوية التاريخية, المدرسة اللغوية التركيبية, المدرسة اللغوية التحويلية – التوليدية, القدرة الإنتاجية

Language is defined from many different points of view. Anthropologists consider language as a form of cultural behaviour. In this respect, the American anthropological linguist Edward Sapir (1834-1939), for instance, identifies language as “a purely human and non-instinctive method of communicating thoughts, desires, and emotions by means of a system of produced symbols”. On the other hand, sociologists define language as a social interaction between members of a particular human society. Whereas, philosophers regard language as a means of interpreting human experiences (Hamash and Abdulla, 1968: 3).

1.1 Language: The Functional Aspect

Language is an essential part of culture. It is a part the human behaviour. Language is an acquired behaviour of systematic vocal activity representing meanings resulted from human experiences. That is to say, language is an acquired vocal system employed for communicating meaning. On the whole, language is regarded as an oral controlled system employed for communication by a particular human society. This reflects the following considerations: (Lyons, 1981: 222)

1. Language works in a systematic way.

2. Language is basically oral and the oral language symbols represent meaning since they are related to real life situations and experiences.

3. Language is a controlled behavioural system.

4. Language has a social function, and without it society would not exist.

5. Language is the most essential means of human communication. It is the most frequently used and the most greatly developed form of human communication.

6. Language is the major material of the study of linguistics. (Ibid: 223)

Al-Khuli (2009: 4) maintains that with language we convey ideas, facts, sciences, and information from age to age, from place to place, and from generation to generation. In fact, without language, there would be no teaching and no sciences.

1.2 Language: The Formal Aspect

Hannounah (1998: 77-8) states that a language can be considered as having two veins: expression and content. For the former, linguistics deals with form of linguistic characters (elements) without necessarily taking their meanings into consideration. From the point of view of form, for instance, “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” (a non-sense sentence established by Chomsky) is a well-formed sentence. On the other hand, the latter (the content vein) deals with semantics, i.e. the scientific study of meaning. Therefore, from the view point of semantics, the aforementioned sentence is refused because it is meaningless.

Al-Khuli (2009: 4-5) states that language manifests itself in several levels: the phonemic level, the morphological level, the lexical level, and the syntactic level. These levels can be discussed as follows:

1. The Phonemic Level (Phonetics and Phonology): On this level we use phonemes (the smallest meaningless units in language), such as /m/, /r/, /k/, /s/, and /i:/. Scientifically, language is similar to matter, i.e., if we analyse matter, we obtain molecules, which if further divided give atoms, which if further analysed give electrons, protons, and neutrons. The lowest level in language is the phoneme level.

2. The morphological Level (Morphology): When phonemes get together, they make morphemes. That is to say, the smallest meaningful units in language are morphemes. For instance, sun, school, street, dictionary are morphemes.

3. The Lexical Level (Morphology, Syntax, Semantics): When morphemes are combined together, they produce words, i.e., lexemes. The words treatments, discourage, dislike, re-write, impossibility are constructed of two morphemes or more each.

4. The Syntactic Level (Syntax): When words get together, they constitute a sentence which grammatically represents the syntactic level of language.

e.g., These students studied physics in Iraq. (Ibid 5)

1.3 Language and Linguistics

In order study language scientifically and intelligently, we must have the instruments and tools for a comprehensive and scientific study of this vital aspect of human behaviour. Linguists state that linguistics is the science that attempts to analyse and understand language its internal structure point of view.

According to Waterman (1963: 60), linguistics is a relatively new branch of knowledge. This science began in (1816) when Franz Bopp wrote an article on the inflectional endings of verbs in Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin, Persian, and Germanic. However, in the next years, many other studies were published that extended man’s knowledge about languages and comparative linguistics. Jacob Grimm, August Schleicher and Karl Brugmann are famous figures who contributed to the early development of linguistic science.

In 1916, linguistic science witnessed am important publication referred to as one of the greatest scientific achievement of the present day linguistics. This was Ferdinand de Saussure’s Cours de Lnguistique Generale (Ibid: 61).

In the same vein, many outstanding American and English linguists greatly contributed to this new science especially linguists like William Dwight Whiteny, Yale (1824-1894), Henry Sweet, Oxford (1845-1912), and the American linguists Edward Sapir (1884-1939) and Leonard Bloomfield (1887-1949) who had a great influence on the development of linguistics. In fact, Leonard Bloomfield’s Language (1933) is a very important scientific guide to students of linguistics (Hamash&Abdulla, 1968:4-5).

Hannounah (1998: 1-2) indicates that linguistics means the scientific study of language. As with other fields of knowledge and scientific study, linguistics must be studied in two ways:

1. in relation to other fields of knowledge, and

2. in the different branches within itself.

Furthermore, the science of linguistics works on two functions:

1. It scientifically studies languages as ends in themselves, in order to produce complete and accurate descriptions.

2. It scientifically studies languages as means to a further purpose, in order to acquire information about the nature of language in general.

Aitchison (1999: 12) indicates that linguistic science has witnessed fast developments in the last fifty years. Consequently, hundreds of books on linguistics have been written and published. So many courses in linguistic science are prepared for colleges and universities in the world. Students of language and literature are now required to study a variety of courses in linguistics. In addition, even students of sociology, anthropology, and education are advised to study certain courses in linguistics because of the inter-relationships that exist among these fields of knowledge (Hannounah, 1998: 1). That is to say, linguistic science has also affected foreign language textbooks in the non-English native countries. In fact, no language book is regarded to be of any value if it is not based on some of the findings of modern linguistics. Furthermore, no language teacher can abandon linguistics if he is expected to do his language teaching tasks effecti8vely and on scientific foundations.

2. The Main Linguistics Schools

As a matter of fact, linguistics has developed very quickly during the 19th and 20th centuries. Many different theories emerged in this field of human knowledge. The purpose of linguistics is to investigate the material and to make general judgements about its various elements that relate to regular rules. In addition, it is an empirical and practical science because the material it deals with can be observed with the human senses. For instance, speech sounds can be heard, the physiological movement of the organs of speech can be seen and noticed with the assistance of scientific instruments, writing can be seen and read. In this concern, the current study deals with the main linguistic schools terms: Historical Linguistic School Terms, Structural Linguistic School Terms, and Transformational-Generative Linguistic School Terms.

2.1 Historical Linguistics School Terms

Before the nineteenth century, language in Europe was mainly studied by philosophers. Indeed, the Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle made essential contributions to the scientific study of language. Plato, for instance, distinguished between nouns and verbs (Aitchison, 1999: 23).

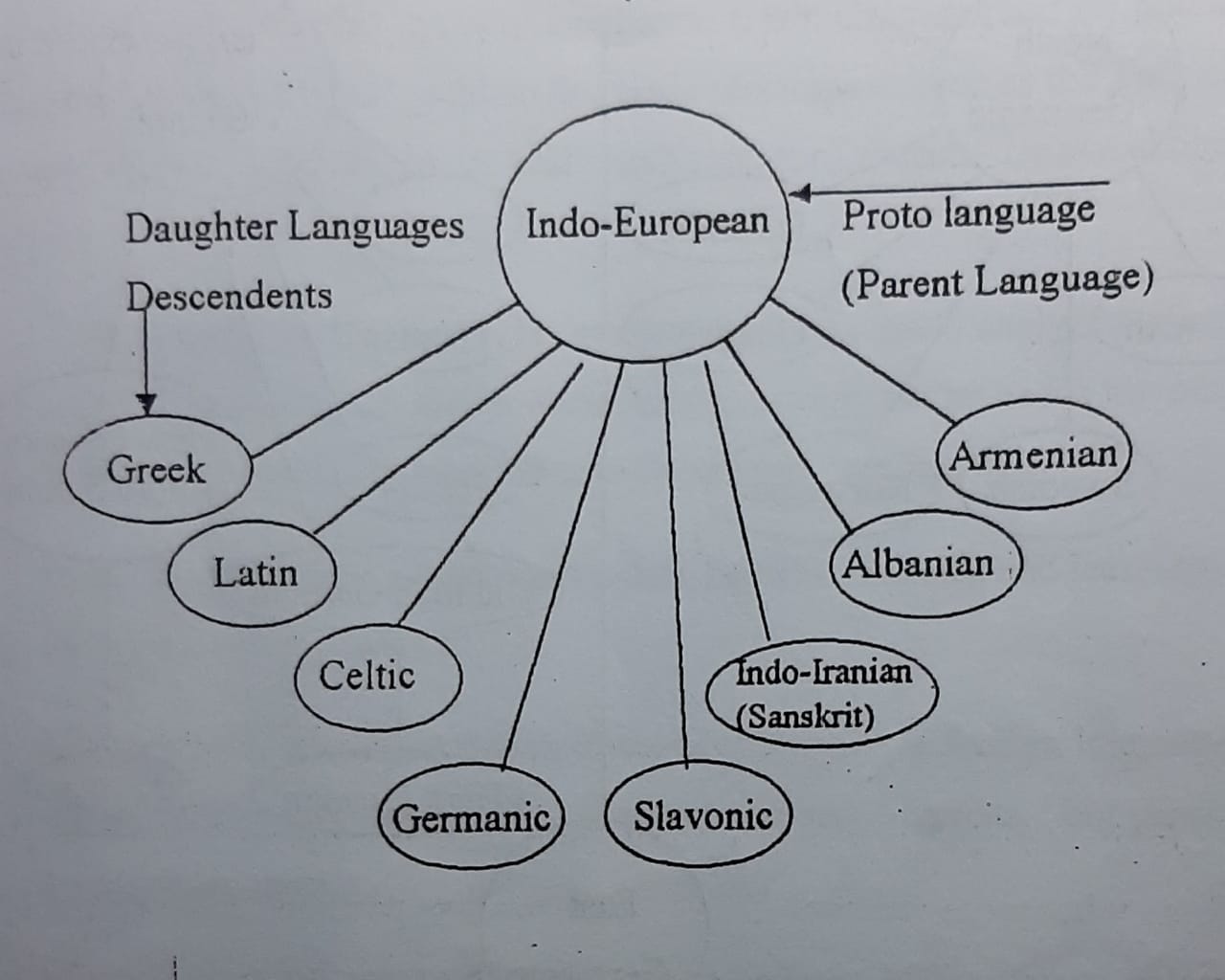

Many people view that the year (1786) is the birthdate of linguistics. In this year, Sir William Jones presented a paper to the Royal Asiatic Society in Calcutta referring to that Sanskrit (the old Indian language), Greek, and Latin all had structural similarities. This vital finding made Sir William Jones think that these languages must spring from one common source. However, several scholars arrived at the same idea at the same time though Sir William Jones was the first person to make this discovery. For the next hundred years, all other linguistic works were eclipsed by the general preoccupation with writing comparative grammars, grammars which first compared the different linguistic forms found in the various members of the Indo-European language family, and second, attempted to establish a hypothesis which reads that English, Greek, Latin, Sanskrit were descended from Proto-Indo-European family. Table (1) illustrates the members of the Proto-Indo-European family (Ibid.).

| Indo-European Language Family | |||||||

| Germanic

(German, English, etc.) |

Celtic

(Welsh, etc.) |

Italic

(Latin, etc.) |

Greek

Language |

Balto-Slavonic

(Russian, etc.) |

Armenian

Language |

Albanian

Language |

Indo-Iranian

Language |

Table (1): Indo-European Language Family (Aitchison, 1999: 23)

Waterman (1963: 5) defines historical linguistics as the branch of language study that deals with the changes languages have undergone with the progress of time. In fact, this study involves changes in the sound system, in morphology, in syntax and in vocabulary. As a matter of fact, through the findings of historical linguistics, earlier forms of human languages, such as Indo-European Languages, are reconstructed.

According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 92-3), historical linguistics is a branch of linguistics that scientifically studies language change and language relationships. Historical linguistics works on comparing earlier and latter forms of a language and also comparing different languages to show that certain languages are related.

Aitchison (1972: 132) states that historical studies of languages thrived in the eighteenth century in Europe. These studies showed certain similarities among the languages studied in Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, etc. Meanwhile, the comparative historical studies of language began in 1786. The founder of those studies is Sir William Jones. Some similarities were found in grammar and phonology as seen in the following example:

| Sanskrit | Greek | Latin | English |

| dasa | deka | decem | ten |

| dva | duo | duo | two |

| hrd | kardia | cordia | heart |

Table (2): Phonological Seminaries among English, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit (Hannounah, 1998: 16)

Table (2) shows that initial and final /t/ in English corresponds to the /d/ in Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit languages. The sound which occupies a particular position in words of one language appears in the same relative position in semantically similar words of the other languages. Whereas Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit preserved an original /d/, native speakers of English through history have changed the pronunciation of their /d/ into /t/. These findings encourage historical linguists to set such languages together in families. Such a grouping process undertakes that these related languages descended from a parent language called “The Proto-Language” that over centuries experienced many changes in its systems attributed to its diversification into several dialects. Consequently, these languages then experienced similar changes and other languages emerged into existence.

In the same vein, Crystal (2003: 135) defines historical linguistics as the term which refers to the earlier study of language in historical terms. Historical linguistics does not differ from dichromic linguistics in subject-matter, but in aims and method. More attention is paid in the latter to the implication of historical work for linguistic theory in general.

2.1.1 Philology

Defined as a linguistic term which was applied to the new study of comparative linguistics from about 1800, in this sense, the names ‘comparative philology’ or the new ‘philology’ have sometimes been used. Today, this term is mostly applied to ‘historical linguistics’ which is concerned with details, rather than with general principles, such as investigating the histories of certain words and names (Trask, 2014: 167).

In the same vein, Rajimwale (2006: 170) defines philology as a traditional branch of language study basically concerned with its historical development. The methods designed were based on comparative analysis at different levels: sounds, lexicons, morphology, grammatical form classes, etc. which dealt with different languages and established their ‘genetic’ affinities thus arriving at mutual relationships. Philology works on discovering different language families on the basis of certain comparisons, and refuses earlier misconceptions about mutual relationships among different languages. The works of philology emerged in 18th century and became a very important discipline of language study in which both linguists and historians, were equally interested.

Furthermore, Razmjoo (2004: 52) states that linguistic study about the common ancestor of human languages began from linguist Sir William Jone’s (18th century). This linguistic investigation still continues and focuses on the historical development of languages and also attempts to show the systematic processes which are involved in language change. In the nineteenth century, the historical investigation of languages, which is known as philology, was the main interest of linguists. Philologists believe that the original form (proto) of languages is the source of modern languages in India and Europe. With Proto-Indo-European as the ‘great grandmother’, linguists set out to show the lineage of many modern languages.

According to philology, the biggest language Family today is the Indo-European family of languages of which English is one branch. It is called ‘Indo-European Family’ because it involves languages spoken in India and Iran like Sanskrit and the Indo-Iranian languages in addition to many other European languages (Hannounah, 1998: 16). The following figure shows the eight main branches of the Indo-European Family (Ibid: 17):

Figure (1): Indo-European Family (Hannounah, 1998: 17)

2.1.2 Traditional Grammar

Traditional grammar is the term which refers to the Aristotelian orientation towards the nature of language as represented in the works of ancient Greeks and Romans. That is to say the works of the prescriptive approach of the eighteenth century grammarians (Hannounah, 1998: 10).

Equally important, traditional grammar assumes that the spoken language is greatly different from the written language where the former is inferior, and to a certain extent, traditional grammarians depend on the standard written language. On the other hand, modern linguists assert that the spoken aspect of language is primary and that writing aspect of language is fundamentally a means of reflecting speech in another medium. Thus, traditional grammar emphasizes on the principle of the priority of the written aspect of language over the spoken aspect of language (Bollinger, 1985: 210). In addition, in traditional grammar, the material presented mostly does not even cover the whole range of the language’s written aspect, but is limited to specific types of writing (Ibid.).

2.1.2.1 The Influence of Latin

Traditional grammarians described English in terms of other languages, especially Latin. Traditional grammarians consider Latin as a model of description in Europe for centuries. In this regard, one of the most common examples is to say “It is I” instead of saying “It is me”. As a matter of fact, traditional grammarians treat English as if it were Latin. But the patterns of English grammar function differently from the patterns of Latin grammar. For example, Latin has six noun cases:

1. nominative → fish

2. vocative → O fish

3. Accusative → fish

4. genitive → of a fish

5. dative → to/for a fish

6. ablative → by/with/from a fish

In fact, English has only two noun cases:

1. The genitive noun case: The case in which we add an (-‘s) or (-s’), e.g., student’s or students’

2. The general noun case: The case which is used everywhere, e.g., student or students.

Therefore, in the description of a language or a part of a language, we must not prescribe findings or standards from the description of other languages. Indeed, English must be described in its own terms and not through Latin terminology. English is a complex enough language without attempting to force more complexities of Latin or any other language into it (Sledd, 1959: 12).

2.1.2. Logic and Language

Traditional grammarians regard Latin as a source of authority which one turn to when investigating the English grammar patterns. On the other hand, there are other authorities in this concern, such as ‘Lotic’. For instance, concerning the way a language is constructed, one may say that English is a more logical language than French or it is more logical to say “spoonfuls” than saying “spoonful”, without basing their descriptions of language structure on scientific facts (Yule, 1996: 122).

As a matter of fact, human language is not a logical concept, though many people think so. It is even not regular. It can change its form over the years and it has so many irregularities. Actually, we cannot apply reasoning to language, for instance, we say ‘big’ → ‘bigger’, ‘small’ → ‘smaller’, but if we apply a reasoning criterion, then we should ‘good’ → ‘*gooder’, ‘bad’ → ‘*badder’ as a correct form. Traditional grammarians say this is a matter of logic without saying exceptions or irregularities giving any language description (Bloomfield, 1933: 234). He (Ibid.) adds that in language we must avoid the word ‘logic’ and to use the terms ‘regular’ and ‘irregular’ to indicate that there is always a tendency for the irregular forms in a language to be made to adopt with the patterns of the regular ones, a process referred to as ‘analogy’ (treating irregular patterns as if they were regular ones). This frequently happens especially in the speech of children saying ‘* mouses’ and ‘*seed’ for ‘mice’ and ‘saw’.

Equally important, Hannounah (1998: 36) states that Traditional grammarians argue that the ‘true’ meaning of a word is its oldest one. For example, they say that the true meaning of the word ‘history’ is ‘investigation’, because this meaning was its real meaning in Greek, or the correct meaning of the word ‘nice’ is ‘fastidious’ as this was its meaning in Shakespeare’s time. In addition, they call a word ‘meaningless’ if it no longer has a certain earlier meaning. That is to say, if we depend on history in explaining meaning, we shall never know the real or correct meaning of the words we use. Moreover, if the oldest meaning of the word is the true or correct meaning, then we can hardly stop with Shakespeare’s time. In this regard, we must trace the meaning of the word ‘nice’, for instance, back into Old French (meant ‘silly’) and in Latin (meant ‘ignorant’) and thenceforward, to ancestor Latin having no clear meaning and absolutely this is not the oldest language in the world. The oldest language in the world lost forever, not written down and therefore without records (Hannounah, 1998: 38).

2.1.3 Diachronic Study

Diachronic study is a linguistic term which refers to the major temporal dimensions of linguistic investigation proposed by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure in which languages are studied from the point of view of their historical development, e.g., the changes that have taken place between old and Modern English could be described in phonological, grammatical, and semantic terms. In the same vein, comparative philology is a branch of historical linguistic studies. It deals with the comparison of the characteristics of different languages or different states of a language through history. Diachronic study compares the different forms of related languages and attempts to re-construct the mother language from which they all developed. It starts with the discovery of the similarities between ancient Sanskrit and other languages of the Indo-European family such as Classical Greek and Latin (Nasr, 1980): 132). That is to say that diachronic study emphasizes on language change through history.

Furthermore, Rajimwale (2006: 74) defines diachronic study as the term which refers to the proposal introduced by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure to propose that a language can be studied in its historical development along with the changes occurring in it. The aim of diachronic study is to know ‘how language changes over a period of time’, for instance, the change in the Sound System of English from Old English to Modern English. Yule (2010: 234) argues that diachronic study is the linguistic term referring to the variation in language based on the historical perspective of change through time. He (Ibid: 233) adds that sound changes, syntactic changes, and semantic changes did not take place overnight. They took place gradually and probably difficult to discern while they were in progress. Although some changes in language can be associated with the main social changes caused by wars and invasions, the most general source of change in language seems to in the continual process of cultural transmission. That is to say, each generation has to find a way of using the language of the previous generation.

According to Crystal (2003: 135), diachronic study is a linguistic term which refers to one of the two major temporal dimensions of linguistic study introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure. In diachronic study (sometimes known as diachronic linguistics), languages are studied from the point of view of their historical evolution, for instance, the changes which have taken place between Old, Middle, and Modern English. In fact, the linguistic term ‘historical comparative philology’, is only different from diachronic study in aims and approaches. As a matter of fact, in the nineteenth century, linguists were more interested in diachronic investigation of language (Hannounah, 1998: 24). Equally important, Richards and Schmidt (2003: 154) state that diachronic study is a linguistic term referring to an approach in linguistics which studies how languages change over time, for instance, the change in the sound systems of the romance languages from their roots in Latin (and other languages) to modern times or the study of changes between Early English and Modern English. In fact, diachronic and synchronic approaches to study language are identified by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure.

2.2 Structural Linguistic (Structuralism) School Terms

Trask (2014: 209-210) defines structuralism as the linguistic term which refers to an approach of the study of language which considers a language to be basically a system of relations. That is to say, the place of every element in the language (word, speech sound, etc.) is explained by the way it relates to other elements in the language. In fact, structuralism was first proposed by Ferdinand de Saussure, and almost all approaches to linguistics since de Saussure have been structuralist approaches, whereas before Ferdinand de Saussure most approaches to the study of language had considered a language as mainly a collection of objects. Equally important, American Structuralism represents a distinctive and unusual form of structuralism. In this regard, some linguists employ the linguistic term ‘structuralism’ only to American Structuralism, which is misleading. As a matter of fact, structuralist ideas in language were imported from linguistics bt Lèvi-Strauss into anthropology, from where they have spread into the social sciences generally and even into literary criticism.

In the same vein, Lyons (1981: 27) identifies structuralism as a linguistic term that refers to a famous approach to study language from the point of view that every language is considered as a system of relations (more precisely a set of inter-related systems), the elements of which (sound, word, etc.) have no validity independently of the relations of equivalence and contrast which hold between them. In Europe there were three different things happening simultaneously:

1. The Missionaries: The missionaries found themselves in many different places all over the world, in Africa, India, etc. They decided to learn the languages of the native speakers of those places in order to communicate with the inhabitants. they produced intensive studies about language depending on native speakers (Lyons, 1981: 213).

2. Ferdinand de Saussure’s Linguistics: Saussure is regarded as the father of modern structural linguistics. His time identified the rapid rise of descriptive linguistics as opposed to historical linguistics (Crystal, 1985: 110).

3. The Neo-Traditional Grammarians: They represent the period from traditional grammar to structural grammar. They follow the traditional concepts but came up with new methods of collecting data. They refuse the traditional view concerning the belief that Latin contains a certain kind of universal rules and linguists should depend on these rule. Indeed, this the main difference between traditional grammar and neo-traditional grammar. However, the have the same general concept. Furthermore, they began to base their rules and descriptions on real data, part of which was collected from native speakers, but much of it was taken from the studies of famous linguists (Ibid.).

Worded differently, there was a separate kind of structural linguistics in Europe not affected by behaviourism in America. The leading psychologist in this area of study was Piaget. Unlike the behaviourists, he had a different view towards the psychology of language, which differs in principles from behaviourism. He presented a truthful account on how humans acquire and use language (Bruce, 1971: 5).

In America, the development of detailed procedures for the study of spoken aspect of language also led to progress in phonetics and phonology, and a special attention was paid to morphology and syntax. Leonard Bloomfield was the leading developer of the twentieth century structuralism in America. He published his ‘Introduction to the Study of Language in 1914 and later his famous book ‘Language’ in 1933. This book dominated the linguistic thinking for over 20 years, in which Bloomfield presented many descriptive works of grammar and phonology (Aitchison, 1999: 25). In this respect, Bloomfield considered that linguistics should deal objectively and systematically with observable data. Therefore, he was more interested in the way items were arranged than in meaning.

Equally important, Saussurean structuralism was further developed in somewhat different directions by other European and American movements. In the United States of America, the tem structuralism (or structural linguistics) has witnessed much the same sense as it has had in Europe in relation to the linguistic works of Franz Boas (1858-1942) and Edward Sapir (1884-1939) and their followers as well. Today, on the other hand, structuralism is commonly used to refer to the so-called post-Bloomfieldian school of language analysis that follows the methods of the American linguist Leonard Bloomfield who developed phonology (i.e., the scientific study of sound systems) and morphology (i.e., the scientific study of word-structure) after 1933. As a matter of fact, little work on semantics has been achieved by structural linguists because they believe that semantics is extremely difficult to describe (Matthews, 2001: 121).

2.2.1 Synchronic Study

The linguistic term synchronic study (non-historical linguistic investigation) is one of the major dimensions of linguistic study identified by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure in the first half of the twentieth century as a reaction to the historical studies on which linguists depended in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. According to synchronic study, languages are scientifically studied at a particular time. That is to say, one describes a state of a language disregarding whatever changes might be taking place (Aitchison, 1999: 10).

Equally important, Hannounah (1998: 15) indicates that synchronic study is a structural linguistic term referring to an approach to linguistic studies in which the forms of one or more languages are studied at a given stage of their development. In fact, synchronic study is the approach followed by modern linguists. Similarly, Yule (2010: 295) defines synchronic study as the term which refers to differences in language form found in different places at the same time. That is to say, synchronic linguistic approach does not consider the historical development of language forms at all. According to Robins (1967: 123), synchronic study is a term referring to the study of language with a view to acquiring particularly accurate information about a language in its current usage. For instance, a synchronic study of English of Chaucer’s time would take the language out of its temporal context and study it in all its structural -and systemic aspects as an entity.

Furthermore, Crystal (1985: 5) argues that linguistics is not to be viewed as a historical (i.e., diachronic) study. In a historical study of language, we see how different languages have developed from older languages, for instance, Modern English is developed from Old English (or called Anglo-Saxon language), French is developed from Latin. In addition, a historical study of language investigates in how older languages in turn have developed from earlier languages, which perhaps no longer exist, for instance, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit languages have developed from the Indo-European language. He (Ibid.) adds that linguistics is in fact primarily concerned with the non-historical (i.e., synchronic) study of language, the study of a state of a language at a particular time. Most of the vital questions raised by the linguist about language are not historical questions at all: What are the roles that language performs in society?, How does language perform them in society?, How do we analyse any language?, Do all languages have the same parts of speech?, What is the relationship between language and thought?, What is the relationship between language and literature? To answer such questions, we must examine language in a non-historical view. That is to say, we must examine language empirically, in its own terms, like the subject-matter of chemistry or physics. In other word, comparative philology is a branch of linguistic study that has been practised in an unprofessional way for many hundreds of years, though not systematically until the end of the 18th century.

2.2.2 Paradigmatic Relations

Defined as a linguistic term which refers to any relation between two or more linguistic units or forms which are competing possibilities. That is to say, one of them may be selected to occupy some particular position in a structure. For instance, all of the various inflected forms of a certain verb represent a paradigmatic relation, because only one of them will be selected to appear whenever that verb is used (Trask, 2014: 161). In the same vein, Hannounah (1998: 26-7) indicates that paradigmatic relation is a structural linguistic term referring to the vertical relationship between linguistic signs that might occur in the same particular position in a particular structure. This dimension of structure can be applied to phonology, vocabulary and any other aspect of language. As a matter of fact, each word in a language is in a paradigmatic relationship with a group of alternatives. This finding is a conception of language as a vast network of inter-related structures known as a linguistic system. The following figure illustrates a paradigmatic relationship:

Syntagmatic Relationship

Paradigmatic She + can + go

Relationship I + will + com

He + may + sit

You might see

Figure (2): Paradigmatic Relationship (Hannounah, 1998: 26)

2.2.3 Syntagmatic Relations

Trask (2014: 2015) discusses syntagmatic relation as a linguistic term referring to a relation between two or more linguistic items which are simultaneously present in a single structure; for instance, the relationship between phonemes constituting a word, or between a verb and its object. Similarly, Lyons (1981: 120) says that syntagmatic relation is the linguistic term which refers to horizontal relationship between elements constituting linear sequences in the sentence, e.g.,

Syntagmatic Relationship

She + can + go

They + will + come

According to Ferdinand de Saussure, language is a system of relations. In fact, he wanted to identify language as an object that can be scientifically studied. He pointed out the structural nature of language, that is to say, its elements are fundamentally inter-related. He compared a language to a game of chess; it is the relationship of each chessman to other chessmen is completely dependent on the position of the other chessmen on the board (Hannounah, 1998: 27). Moreover, Richards and Schmidt (2002: 534) define syntagmatic relations as a linguistic term that refers to the relationship that linguistic units in a particular structure (i.e., words, phrases) have with other units because they may occur together in a certain sequence. For instance, a word may be said to have syntagmatic relationships with the other words which occur in the sentence in which it appears. For example,

She ↔ gave ↔ Ahmed ↔ the ↔ dictionary (↔ = Syntagmatic Relationships)

2.2.4 Langue

Defined as a structural linguistic term used in Ferdinand de Saussure’s classification in which language is identified as a system shared by a community of speakers, approximately as linguistic competence (Trask, 2014: 127). Richards and Schmidt (2002: 295) state that langue is a French word for language. It is a linguistic term used by the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure to identify the system of a language, that is the arrangement of sounds and words which speakers of a language have a shared knowledge of or, as de Saussure said “agree to use”. Langue is the ‘idea’ form of a language.

2.2.5 Parole

Crystal (2003: 336-7) defines parole as a French term introduced into the scientific study of language by Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) to identify one of the definitions of the word ‘Language’. This term refers to the physical or actual utterances produced by individual speakers in real situations. Parole is distinguished from another term ‘Langue’ which is identified as the collective language system of a speech community.

In the same token, Trask (2014: 162) indicates that parole is the linguistic term which refers to the actual use of language in both spoken and written aspects. It is the particular utterances articulated by particular speakers on particular occasions, that is to say, this term is approximately similar to performance.

2.2.6 Signifier and Signified

Defined as terms used in structural linguistics. Ferdinand de Saussure identified two aspects of the study of meaning. He emphasized that the relationship between these two sides is arbitrary. They are:

1. Signifier (significant): the thing that signifies / sound image) and

2. Signified: the thing signified / concept.

Ferdinand de Saussure regarded the relationship between the two aspects of the study of meaning “a linguistic sign”. The sign is the essential unit of communication within a community. Therefore, language is seen as a system of signs (Atkinson, at el. 1982: 8). The following figure represents the two sides of the study of meaning (Hannounah, 1998: 25).

Sound Image “House”

(Signifier) (Signifier)

………………………… ………………………

………………………… ………………………

Concept

(Signified)

(Signified)

Figure (3): Signifier & Signified (Hannounah, 1998: 25)

According to Trask (2014: 133), signifier is a term employed in structural linguistics to mean the combination of a linguistic form and its meaning or function. In the same vein, Richards and Schmidt (2002: 485) indicate that in linguistics, the words and other utterances of a language which signify, that is to say, stand for other things are considered by some linguists as signifiers. For instance, in Arabic, the word “طاولة” stands for a particular piece of furniture in the real world.

Furthermore, Gleason (1961: 210) defines signifier and signified as terms employed by Ferdinand de Saussure in structural linguistics. The former refers to the material form, i.e., the physical form of the sign (word, utterance). That is to say, the element which we can see, hear, touch or smell. On the other hand, the latter refers to mental concept associated with a sign. That is to say, it is the concept, meaning or the thing associated with the thing it stands for. For example:

Signifier: the word “open”

Signified: The shop is open now.

A sign (word or any other utterance) must always have both a signifier and a signified. Ferdinand de Saussure identified the relationship between signifier and signified as ‘signification’. At the same time, it is also important to notice that the same signifier can be used for different concepts. This is due to the fact that the relationship between the signifier and the signified is sometimes arbitrary. For instance, the word (signifier) ‘pain’ has the meaning ‘hurt’ or ‘discomfort’, but in French, it means ‘a loaf of bread’. The following table illustrates the main differences between signifier and signified (Matthews, 2001: 213):

| The Main Differences between Signifier and Signified

in Structural Linguistics |

|

| Signifier is a sing’s concrete (physical) form | Signified is the meaning or idea expressed by a sign. |

| Examples | |

| Signifier can be a printed word, sound, image, etc. | Signified is a concept, object, or idea. |

| Relationship | |

| A signified cannot be exist without a signifier | |

Table (3): Signifier and Signified in Structural Linguistics (Matthews, 2001: 213)

2.2.7 Discovery Procedure (Am.)

Identified as a linguistic term introduced by American structuralists which refers to an explicit mechanical procedure for constructing a grammar from a corpus of data in a particular language. American structuralists considered the formulation process of a discovery procedure as a main scientific process linguistics (Trask, 2014: 71). Furthermore, Crystal (2003: 143) defines discovery procedure as a linguistic term which refers to a set of techniques which can be mechanically applied to a sample of language and which will make or produce an accurate grammatical analysis. As a matter of fact, developing grammatical procedures identified the linguistic works of many Bloomfieldian linguists. On the contrary, generative grammarians strongly criticized discovery procedure arguing that it is extremely difficult to identify all the factors which lead a linguist in the direction of a certain linguistic analysis. In the same vein, Aitchison (1999: 26) states that discovery procedure is term used in structural linguistics. It refers to a set of principles which enable a linguist to more accurately discover the linguistic units of an unwritten language.

2.2.8 Corpus (Am.)

Trask (2014: 57) defines corpus as a linguistic term used first in structural linguistics which means a collection of spoken or written texts in a particular language which was created by native speakers and which is available for linguistic description, in this regard, corpus linguistics is defined as any approach to linguistic description which largely depends on the use of corpora. Equally important, the availability of computers has made this approach an increasingly important aspect of the subject. Similarly, Crystal (2003: 112) identifies corpus as a linguistic term employed first by structural linguistics to refer to a collection of linguistic data, either written texts or a transcription of recorded speech, which can be applied to linguistic description, or as a means of verifying hypotheses about a language.

2.3 Transformational-Generative Linguistic School Terms

In 19557, at the highest structuralism’s influence on linguistic studies, Noam Chomsky, a professor working at the Massachusetts Institute of Linguistics and Technology, published his famous book entitled ‘Syntactic Structures. In fact, this book challenged many of the beliefs of linguistics in his theory of language structure identified as T.G.G. (Transformational Generative Grammar). In ‘Syntactic Structures, 1957’, Chomsky severely criticized the structural linguistic approach to linguistic study. In fact, he argued that the entire structuralist theory had been based on wrong assumptions refusing their method of linguistic description (i.e., data-collecting techniques and classification of data). In ‘Syntactic Structures, 1957’, Chomsky developed the conception of ‘generative grammar’ in language which is completely different from the structuralism and behaviourism theories. In this new linguistic school ‘generativism’, Chomsky’s proposals aimed at discovering the mental realities underlying the way humans use language. Therefore, the effect of the mentalism school is most marked in his work especially in his notion of ‘competence’ and ‘innateness’ and in his general view concerning language and mind indicating that “mental processes can explain behaviour” (Hannounah, 1998: 54-55). The Generative Linguistic School has undergone several stages of development: (Aitchison, 1999: 184).

1. From 1957 to 1964, the transformational-generative theory of language concentrated basically on syntax rather than on semantics. Chomsky argued that “a grammar model should be based on syntax rather than on semantics. Syntax is an independent component of a grammar system. This reveals that the early stage of the transformational-generative school was concerned more with form than meaning. Therefore, in 1957, transformational-generative linguists followed the linguistic ladder: syntax → phonology → semantics. That is to say, syntax is the core of linguistic study and we first need sentences to express our thoughts and ideas not sounds.

2. In 1965, Noam Chomsky modified his linguistic theory as he published his famous book entitled ‘Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965)’. Indeed, this book is regarded as the most influential book of grammar in the second half of the 20th century. According to this linguistic model, the linguistic should ladder should start with semantics, syntax, and phonology. In this respect, syntax is still central and most important than the other disciplines of linguistics (Ibid. 185).

2.3.1 Deep Structure and Surface Structure

Hannounah (1998: 60) defines deep structure as a linguistic term used in transformational-generative linguistic theory which refers to the abstract syntactic representation of a sentence (also referred to as an underlying or base structure of the sentence. That is to say, it is the original form to which no change has happened yet. It processes with competence in the mind:

Competence → Deep Structure → Sentence

e.g., Ali cut Ali.

Equally important, Crystal (2003: 125) defines deep structure as a central theoretical term used in transformational-generative theory. It is the abstract syntactic representation of a sentence in language. It is the essential level of structural organization which involves all the factors controlling the way the sentence should be interpreted. In addition, deep structure provides information which enables us to recognize the difference between the alternative interpretations of sentences which hold the same structural form (i.e. the same surface structure), e.g.,

In the sentence ‘Flying planes can be dangerous’, (flying planes) could refer to two basic sentences:

1. Planes which fly can be dangerous.

2. To fly planes can be dangerous.

Furthermore, deep structure is also the way of relating sentences which have different surface structural forms but the same basic meaning, as in the relationship between ‘active and passive structures’, e.g., (1) The lion chased the man. (2) The man was chased by the lion (Ibid: 126).

On the other hand, surface structure is defined as a linguistic term used by transformational grammarians to refer to a representation (usually a tree structural representation) of the structure of a sentence (Trask, 2014: 213). In addition, Hannounah (1989: 61) defines surface structure as transformational-generative linguistic term which refers to the final stage in the syntactic representation of a sentence. That is to say, the form which has received one or more changes. It embodies performance in speech or writing:

Performance → Surface Structure → Transformed Sentence

e.g., Ali cut himself.

Equally important, Smith and Wilson (1979: 251) indicate that structuralists cannot differentiate between sentences which have the same surface structures, but different deep structures. Whereas transformational-generative linguists can differentiate between such sentences and also analyse any ambiguous sentences, e.g.,

1. John is eager to please.

2. John is easy to please.

Structural linguists indicate that these two sentences are alike because they depend on the surface structure of the sentence, but Chomsky in his famous book Syntactic Structure (1957) explains the difference between them referring to their deep structures, arguing that: In the sentence “John is eager to please’, John pleases somebody, whereas “John is eager to please’, somebody pleases John.

2.3.2 Generative Theory

Richards and Schmidt (2002: 221) define Generative Theory as a general term which refers to a variety of linguistic theories that have the following common aims:

1. Providing an account of the formal properties of language. That is to say, the rules which identify how to form all the grammatical sentences of a language and no ungrammatical ones.

2. Explaining why grammars have the properties they do and how children acquire them in a short period of time.

As a matter of fact, the main version of Generative Theory which is all associated with outstanding works of the American linguist Noam Chomsky and also has largely influenced the areas of first and second language acquisition is the Transformational-Generative Grammar (T.G.G.). It is the early version of the Generative Theory which emphasized the relationships holding between sentences that can be identified as ‘transformations’ of each other, for instance, the relationships holding between simple active declarative sentences e.g., (Sami went to the college of physics), (Sami didn’t go to the college of physics), and questions (Did Sami go to the college of physics?), such relationships can be accounted for transformational rules (Ibid. 222).

2.3.3 Generative Grammar

According to Trask (1999: 67), generative grammar is a linguistic term which refers to a grammar of a particular language which is capable of identifying all and only the grammatical sentences of that language. The concept of generative grammar was proposed by the American linguist Noam Chomsky in the 1950s. Generative Grammar has largely influenced the scientific study of language. As a matter of fact, early approaches to grammatical description had depended on drawing generalizations about the observed sentences of a language. Noam Chomsky argued to go further in the respect: once our generalizations are precise and complete, they can be turned into rules which can then be employed to build up complete grammatical sentences. Equally important, Yule (2010: 97) indicates that generative grammar is the linguistic term which refers to the small and finite (limited) set of rules which can be used to ‘generate’ or produce sentence structures and not just describe them.

2.3.4 Transformational Grammar

Transformational grammar is identified as a linguistic term which refers to a certain type of generative grammar. In the 195s, the American linguist Noam Chomsky proposed the notion of generative grammar, which has greatly influenced modern linguistics. At present, there are many different types of generative grammar that can be precisely identified. In fact, Noam Chomsky himself discussed many quite different types of generative grammar. But, from the beginning, he himself focused on a certain type of generative grammar which he called transformational grammar (TG). However, transformational grammar (TG) is also called transformational-generative grammar (TGG) (Trask, 1999: 212).

Furthermore, transformational grammar (TG) is a theory of grammar which holds that a sentence typically has more than one level of structure: deep structure and surface structure. According to Chomsky’s view, the meaning of a sentence can be decided much more from its deep structure. Transformational grammar has developed through many different versions. Noam Chomsky’s (1957) Syntactic Structure provided only a partly and general outline of a very simple type of transformational grammar. But in 1965, Chomsky’s Aspects of the Theory of Syntax proposed a very different, and much more complete version. This version is known as the Standard Theory. According to the transformational grammar (TG), the structure of a sentence is first built up using only context-free rules, which are a simple type of rule widely used in other types of generative grammar. The structure which results is known as the deep structure of the sentence. After this step, some further rules apply. These rules are called transformations, and they are different in nature. Transformations have the power to change the structure which is already present in a number of ways: not only can they add new material to the structure, but they can also change material which is already present in various ways, they can move material to a different position, and they can even delete material from the structure altogether. When all the relevant transformations have completed applying, the resulting structure is the surface structure of the sentence. Because of the vast power of transformations, the surface structure of the sentence may seem extremely different from its deep structure (Ibid: 213).

Equally important, Richards and Schmidt (2002: 222) define transformational grammar (also called transformational-generative grammar) as a linguistic term which refers to an early version of the linguistic theory which emphasize the relationships among sentences that can be regarded as transformations of each other, for instance, the relationships holding among simple active sentences (e.g., Susan went to the institute of English language teaching), negative sentences (e.g., Susan didn’t go to the institute of English language teaching, and questions (e.g., Did Susan go to the institute of English language teaching?). Such relationships can be processed by ‘transformational rules’.

2.3.5 Universal Grammar (UG)

According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 570-571), universal grammar (UG) is defined as a modern linguistic term which refers to a theory which is based on grammatical competence of every person regardless to what language he/she speaks. Scholars of modern linguistics claim that every speaker knows a set of principles which can be applied to all languages. In addition they (Ibid.) claim that every speaker knows a set of parameters which vary from one language to another, but they function within certain limits.

Hannounah (1998: 59) states that universal grammar (UG)was identified by Noam Chomsky and has been employed more specifically in his model of government/blinding theory. She (Ibid.) adds that according to universal grammar theory, acquiring a language means employing the principles of universal grammar (UG)theory to a certain language, e.g., French, English, or German, and learning which value is accurate and appropriate for each parameter. For instance, one of the principles of university grammar (UG) is Structural Dependency. This principle means that a knowledge of the language depends on knowing structural relationships in a sentence rather than looking at it as a sequence of words.

On the other hand, Lyons (1981: 213) argues that the role of universal grammar (UG) in second language acquisition is still under discussion. Three views are identified in this respect:

1. Universal grammar (UG) works in the way for second language acquisition as it works for first language acquisition.

2. The learner’s core grammar is fixed and universal grammar (UG) is no longer affects second language acquisition.

3. Universal grammar (UG) partly works for second language acquisition.

2.3.6 Linguistic Competence

Lyons (1968: 121) defines linguistic competence as a linguistic term used in Transformational-Generative Grammar. As a matter of fact, the concept of competence and performance matches Ferdinand de Saussure’s concept of ‘langue’ and ‘parole’. Similarly, Yule (1996: 211) states that linguistic competence is the implicit knowledge native speakers have about their own language. It is the knowledge that helps them relate the sound and the meaning together.

According to Trask (2014: 48), linguistic competence is the term which refers to an abstract realization of a speaker’s knowledge of his/her language, regardless to such anatomy factors as slips of the tongue or memory limitations. Richards and Schmidt (2002: 93-94) define linguistic competence as a linguistic term which is employed in generative grammar as the implicit system of rules that forms a speaker’s knowledge of language. This also includes a person’s ability to produce and understand sentences, including sentences that have never heard before. For instance, a native speaker of English would accept the sentence: ‘I want to go home’ as an English sentence, but would not accept the sentence: ‘I want going home’, even though all its words are English words.

Equally important, Crystal (2003: 87-88) identifies linguistic competence as a term used in linguistic theory (especially in generative grammar), to refer to a speaker’s knowledge of his/her language. That is to say, the system of rules which the speaker has mastered so that he/she is able to produce and recognize an indefinite number of sentences, and recognize grammatical mistakes and ambiguities. He (Ibid.) describes linguistic competence as an idealized conception of language.

2.3.7 Linguistic Performance

Linguistic competence is defined as a linguistic term which refers to the actual use of competence in real situations. Linguistic performance is represented in the form of speech and writing. According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 392), linguistic performance is a linguistic term used in generative grammar to refer to a person’s actual use of language. There is a clear difference between a person’s knowledge of a language (i.e., linguistic competence) and how a person uses this knowledge in producing and understanding sentences (i.e., linguistic performance). For instance, people may have good linguistic competence to produce a long grammatical sentence but when they actually try to use this knowledge (i.e., to perform this knowledge) there are some reasons why they restrict the number of adjectives, adverbs and clauses in any one sentence.

Linguistic performance is a linguistic term which refers to the actual use of language behaviour, that is to say the use of language in daily life. Linguists are mostly interested in competence, whereas other scholars in other fields are usually interested in performance which is the actual use of language by individuals in speech and writing (Yule, 1996: 131). The following table illustrates a difference between linguistic competence and linguistic performance as Cullicover (1997: 2) indicates:

| What people actually say | What is in the mind |

| Language | Grammar |

| E-language (External Language) | I-language (Internalized Language) |

| Linguistic Performance | Linguistic Competence |

Table (4): A Distinction between Linguistic Competence and Linguistic Performance Cullicover’s (1997:2)

2.3.8 LAD (Language Acquisition Device)

LAD (Language Acquisition Device) is defined as a generative linguistic term which refers to a model of language learning in which the baby is naturally provided with an innate ability to acquire language structure. On the other hand, this view is different from the view of language acquisition based on the process of imitation-language learning (Crystal, 2003: 8).

In fact, a child acquires his first language through a variety of mechanisms as different theories assert:

1. LA (language acquisition by imitation)

2. LA (language acquisition by reinforcement)

3. LA (language acquisition by innate readiness). In this regard, generative linguists believe that language acquisition takes place because man is created with the innate nature ability to acquire language (Wanner and Gleitman, 1982: 311).That is to say, language acquisition takes place depended on the nature of man as created by Allah (Alkhuli, 2009: 182).

3. CA (Complementary Acquisition): In this respect, the researcher holds that no one previous views can completely be taken into consideration for language acquisition. In fact, each of imitation, reinforcement, and innate readiness has a key role in language acquisition.

2.3.9 Government Concept

Defined as a linguistic term which refers to the grammatical phenomenon in which the presence of a certain word in a sentence requires another word which is grammatically associated with it to appear in a particular form. In this regard, most personal pronouns in English take place in different case forms: the nominative and the objective. For instance, (I/me), (she/her), (they/them). When a preposition accompanies one of these pronouns as its object, that pronoun must appear in its objective form: (with me), not (*with I); (for her), not (*for she). Here we state that the pronoun governs the case of its object (or simply that the proposition governs its object).

According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 228), government is defined as a grammatical term which refers to a type of grammatical relationship holding between two or more elements in a sentence, in which the choice of one element causes the selection of a certain form of another element. As a matter of fact, in traditional grammar, the term government has characteristically been employed to refer to the relationship holding between verbs and nouns or between prepositions and nouns. In Government/Blinding Theory (developed by Noam Chomsky), the concept of government is founded on traditional grammar but it has been more firmly identified and structured into a complex system to display the relationship of one element in a sentence to another element. For instance, the English verb ‘give’ in the sentence (Susan will give them to me) governs ‘them’ because they are in certain structural relationships to each other (Ibid.).

Equally important, Crystal (2003: 205) indicates that government is a linguistic term that is used in grammatical analysis to refer to a process of syntactic relationship whereby one word (or word-class) requires a specific morphological form of another word (or class). For instance, prepositions in Latin are claimed to ‘govern’ nouns. On the other hand, the term government is usually contrasted with the term agreement where the form taken by one word requires a corresponding form in another, for example, the third person singular subject ‘Ali’ must be followed by the form of the verb ‘go’ that is also marked for third person singular as in (Ali goes to work early).

2.3.10 Linguistic Intuition

Defined as a term used in linguistics referring to the judgements of speakers about their language, especially in deciding a particular sentence is acceptable or not, and how sentences are inter-related to each other. In fact, native-speakers intuitions are always a critical form of evidence in language analysis, however, they are given a special significance in generative grammar because the American linguist Noam Chomsky considers linguistic intuitions as part of data which the grammar should account for (Crystal, 2003: 248).

Equally important, Trask (1999: 88) states that in the 1950s, Noam Chomsky identified a new dramatic proposal arguing that important facts and data about a certain language could be obtained directly from its native speakers’ intuitions. That is to say, Chomsky and his followers argue that you could discover important facts about your own language simply by asking yourself questions like: ‘Is grammatical construction Y acceptable?’ and if it is acceptable, ‘What does it mean?’, ‘How would you say X?’, ‘Is Y a possible form?’. On the other hand, he (Ibid: 89) argues that many linguists reject intuitions as a evident and consistent source of facts. In this regard, the American sociolinguist William Labov devoted considerable attention to the problem of obtaining evident and consistent information and facts about usage that require neither direct questions nor merely waiting for the required information to turn up by chance, and he devoted some professional techniques for doing this.

Similarly, Richards and Schmidt (2002: 250) state that linguistic intuition is a linguistic term which refers to the knowledge that native speakers of a particular language can show (by their language behaviour and their judgements about the grammatical structures as well). In fact, linguistic intuition is implicit knowledge. For instance, native speakers of English intuitively (i.e. implicitly) explicitly use the English articles (definite article, indefinite article, or zero article) , but they do not know the principles of these articles. That is to say, EFL learners may have quite much explicit knowledge about the rules for using English articiles while their linguistic production may show that this explicit (E-Language) knowledge has not been internalized (I-Language) (Al-Hamash (1964: 132).

3. Test Design

It has been indicated that the purpose of test for researchers, academics, and teachers is to find out the learners’ ability in a given linguistic discipline. In this concern, the researcher designed a one-part questionnaire including twenty question items. This questionnaire which is devised to measure the Iraqi EFL college learners’ productive ability in the three main linguistic schools demands the learners at issue to write appropriate terms to complete the twenty scientific statements presented in the questionnaire, a procedure Al Hamash and Al Jubouri (1985) assert.

This test can be considered as an achievement test because it looks back over a long term learnability of a learner as Harrison (1983: 6) argues. In order to achieve the purpose of the test, the questionnaire under scrutiny incorporated major terms used in the main linguistic schools:

1. Historical Linguistic School

2. Structural Linguistic School

3. Transformational-Generative Linguistic School

Items (6), (14), (8), (19), (11), and (7) represent the first linguistic school key terms handled in the current study, which are: (Philology, Traditional Grammar, Diachronic Study). Since there are very few terms used in this linguistic school, the present study handles three linguistic terms and each one is given in two question items. Items (1), (5), (10), (15), (18), and (20) represent the most important terms used in the second linguistic school discussed in this study: ( Synchronic Study, Paradigmatic Relations, Syntagmatic Relations, Discovery Procedure, Corpus, Parole).

Items (2), (3), (4), (7), (9), (12), (13), and (16) investigate EFL college learners’ productive ability in the mostly used terms in Transformational-Generative Linguistic School. Since there are so many linguistic terms used in this linguistic school, eight terms are raised in this study and each one is give a single question item in the questionnaire: (Deep Structure, Generative Grammar, Transformational Grammar, Universal Grammar, Linguistic Competence, Linguistic Performance, Surface Structure, Government Concept)

After the questionnaire had completed, (100) 4th year students from the Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, University of Babylon were randomly chosen as a representative sample of the Iraqi EFL college learners. The twenty items of the test are precisely formed to cover the key terms used in the three main linguistic schools. Moreover, the items of the test are also worded according to certain conventions with respect to linguistically practical criteria as Davies (1990: 101-117) asserts. So that ambiguity is completely excluded. As such each item specifically and precisely requires no more than a specific response.

4. Results and Analysis

After surveying the general outcomes demonstrated by the statistical values assigned to the subjects’ contribution to their reaction to the production of linguistic schools terms, one can say that Iraqi EFL college learners’ performance in this regard is on the brink of abyss. Such determination is attributed to linguistic and non-linguistic factors and causes. Non-linguistic context, maintains Yule (2010: 129), influences and governs the issuance of linguistic forms made by language users. The following accounts will be of help in this concern.

4.1 Iraqi EFL College Learners’ Contribution to Historical Linguistic Terms

Out of favour for foreign learners of English, linguistic terms are characterized by unfamiliar structure and lengthy forms. Accordingly, they do not access to the linguistic concepts the terms are employed to name them. Additionally, Iraqi EFL learners lack desire to acquire historical terms and what Schmidt (2002) calls as aptitude which all linguists think essential in learning a second or foreign language. In consequence, only (31%) of the Iraqi EFL subjects respond correctly to items (6) and (14) whose answers demand the historical linguistic term philology as illustrated in Table (5) and Figure (4). It should be noted that the historical linguistic term philology rhyme with phonology in their phonetic form and approximately is similar to phonology in its spelling and, therefore, confusion would arise in this paradigm. Being so, some students have used the linguistic term phonology instead in their answers.

Similarly, items (8) and (19) which receive only (29%) of the correct answers as illustrated in Table (5) and Figure (4) also show the same defect in Iraqi EFL college learners’ performance in the above-mentioned items that require the historical linguistic term traditional grammar. This challenge, it should be noted is related to the sketchy accounts on historical linguistics which many theoretical judgements are not important. Aitchison (1999), for instance, introduces a curtailed space for this school of thought in her publication so-called ‘Linguistics’. Put differently, textbooks on linguistics provide brief accounts on historicism and its terms while non-textbooks like Crystal’s (1985) ‘Linguistics’ dealing with this linguistic theory which attracts most grammarians and motivate them to write on comparative grammars of some languages.

Items (11) and (17) , which concern the diachronic terms that Ferdinand de Saussure (1916: cited in Aitchison, 1999: 20-3) asserts their sterility in comparison with synchronic ones, show a sharp defection in the EFL learners’ responses as showed in Table (5) and Figure (4), an indication of their incompetence in this regard. This concept is thought to be processed by the learners; yet it is seen as a daunting challenge by the respondents in question. That is to say, diachronic study of language, as a linguistic label, is more difficult than its alternative one, i.e., historical study. It should be noted the latter term, though rarely written, is reported in some responses of the subjects.

4.2 Iraqi EFL College Learners’ Achievement in Structural Linguistic Terms

Highly impressed by the structural linguistic approach which lasts for over 30 years in Iraq, Iraqi EFL college learners did well in their production of the terms denoted to this theory. As a result, they score (56%) of the questions denoted to them in this realm as illustrated in Table (5) and Figure (5); that is to say more than half of the subjects can respond properly and appropriately. Such success is related to the amount of exposure to the linguistic input obtained from the verbal and/or written sentences produced by teachers of English especially in the secondary school, an exposure which Noam Chomsky (1965, cited in Lyons (1981: 81-5) describes as an indispensible part of linguistic interaction and communication.

Fifty percent of the responses are made correctly by the subjects with respect to synchronic study of language which Ferdinand de Saussure adopts in his theory distinguished from diachronic study of language. Such orientation is interpreted as the learner’s desire to engage in linguistic analysis and contribution to language learning and teaching as Schmidt (2002) emphasizes, because these learners got fed up with the postulates of traditional grammar and historical linguistics which pursue the historical developments of linguistic forms and meanings. Simultaneously, paradigmatic / syntagmatic dichotomy is the perusal of these respondents where the correct answers register (48%) and (52%) respectively as illustrated in Table (5) and Figure (5). The correct production of the aforementioned labels stems from the learners’ interests in discovering the linguistic forms that can substitute each other syntactically and semantically on the other hand, and those who deal with the linear relations holding between linguistic forms that are already present in the linguistic stretches that form a well-formed sentences as Aitchison (1999: 11-15) argues.

Item (15), which concerns itself with discovery procedure term which Crystal (1985) condemns as illogical and unscientific because it lacks objectivity, shows some progress on the behalf of the students concerned simply because it scores (60%) of the responses correctly as showed in Table (5) and Figure (5). Accustomed to such a concept which involves the artificial mechanism by which the American structural linguists can analyse the data whose analysis is not stated in the corpus, which is the main concern of American linguists. Iraqi EFL learners are enormously exposed to the concepts and label of American Structuralism whose tenets are present and applied in Iraqi secondary schools curricula which attract Iraqi teachers and students for ages. Put diffeeently, the American Structural Approach was so influential that it is very difficult for Iraqi scholars to root out.

Similarly, corpus term, which anchors in item (18), displays some linguistic development by Iraqi EFL college learners approximating to (62%) of the correct responses as showed in Table (5) and Figure (5). It is worth mentioning that corpus, which is stigmatized by Chomsky (1965, cited in Lyons, 1968: 112), makes appeal to linguists and philosophers of language over twenty years. Stated otherwise, Iraqi EFL syllabus are based on the postulates of the structural approach which was valid all over the world. In some responses, there are annotative reactions to this item; some respondents have written the term ‘data collection’ as an alternative answer. This signals the linguistic knowledge the learners at hand have in their disposal. Nonetheless, there exist irrelevant reactions that disclose the learners’ deficiency in this linguistic area.

Embarking on item (20) which demands the learner to come up with the linguistic term parole as an appropriate response, Iraqi EFL college learners got (64%) of their responses correctly as illustrated in Table (5) and Figure (5). This achievement, though unexpectedly stated by the learners at issue, has scored (64) correct answers (out of 100), an outstanding outcome which signals these subjects’ advancement in this branch of linguistic knowledge. Defined as a manifestation of linguistic output by Crystal (2003), parole is claimed not to be easily absorbed, so to speak, by foreign learners. However, this concept is processed easily by Iraqi EFL college students and success is, nonetheless, registered in this respect.

All in all, the EFL learners’ achievement in producing linguistic terms, in particular those associated with linguistic schools, is still an impediment and grave difficulty.

4.3 Iraqi EFL College Learners’ Productive Ability in Transformational-Generative Linguistic Terms

Though highly attractive to all scholars and linguists, transformational-generative school, which is founded by Noam Chomsky and his associates, represents a daunting challenge for all foreign learners, including Iraqis, of English. One reason for this difficulty, Lyons (1981: 72-80) affirms, is associated with the detailed and logical description of linguistic processes that take place to engender well-formed sentences; that is to say there are many stages and operations through which a sentence passes through in order to create a well-formed utterance. Such abstract and concrete operations, along the multiple transformations, are not easily realized by non-native speakers like Iraqis. Deep Structure seems difficult to absorb, so to speak, by Iraqi EFL learners and this is demonstrated by the low rate (18%) of correct answers scored by the learners in question as illustrated by Table (5) and Figure (6). Approximately similar percentages (20%) and (22%) are registered for the transformational-generative linguistic terms of generative grammar and transformational grammar as shown in Table (5) and Figure (6), an indication that those respondents have very little, if any, information with regard to these labels.