Enhancing EFL College Students' Recognition and Production Abilities of Linguistic Terms Related to Morphology

تقصي استخدام طلبة المستوى الجامعي العراقيين الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية لمصطلحات المورفولوجيا

Hassanein Saleh Swadi1, Asst. Lect. Dr. Yousuf T. Hilal Al-Amaya2

1 Al-Muthanna University, Faculty of Education for Human Sciences, Department of English, Iraq.

E-mail: hassaneinsaleh3@gmail.com

2 Asst. Professor and supervisor of the research, Al-Muthanna University, Faculty of Education for Human Sciences, Department of English, Iraq. E-mail: yousuf.hilal@mu.edu.iq

DOI: https://doi.org/10.53796/hnsj64/1

Arabic Scientific Research Identifier: https://arsri.org/10000/64/1

Volume (6) Issue (4). Pages: 1 - 21

Received at: 2025-04-07 | Accepted at: 2025-04-15 | Published at: 2025-05-01

Abstract: The current study investigates the Iraqi college learners' abilities to handle morphological terms as a main part of EFL learners' grammatical competence. In this study, morphological terms are classified into two types: General Morphological Terms and Word-Formation Terms. It is worth mentioning that this study is restricted to the morphological terms that are of concern to the EFL university students because such terms represent rather important part of grammar, than minor concepts and details. After surveying such terms, the researcher devised a questionnaire prepared for a representative sample of (100) Iraqi EFL college students chosen randomly from the 3rd year stage (academic year 204-2025) in the Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, Al Muthanna University, Iraq with the purpose of investigating those learners' abilities in this respect.

Keywords: EFL University Learners, General Morphological Terms, Word-Formation Terms, Grammatical Competence.

المستخلص: إن الدراسة الحالية تبحث في قدرات المتعلمين العراقيين على المستوى الجامعي الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية لغة أجنبية في التعامل مع مصطلحات المورفولوجيا بكونها جزء رئيسي من الكفاءة النحوية لمتعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. في هذه الدراسة, فأن مصطلحات المورفولوجيا تصنف إلى نوعين: مصطلحات المورفولوجيا العامة و مصطلحات تشكيل الكلمة. و من الجدير بالذكر فأن هذا البحث محدود بمصطلحات المورفولوجيا التي تصب في اهتمام طلبة المستوى الجامعي الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية و ذلك لكون هذه المصطلحات تمثل جزءا هاما جدا من النحو أكثر من المفاهيم و التفاصيل الفرعية. و بعد اجراء المسح لهذه المصطلحات, فأن الباحث قد صمّم استبانة اختبارية اعدت للعينة التمثيلية المكوّنة من (100) من طلبة المستوى الجامعي العراقيين الدراسين اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية, المرحلة الثالثة, للعام الدراسي (2024-2025), قسم اللغة الإنجليزية, كليّة التربية للعلوم الإنسانية, جامعة المثنى, العراق لغرض البحث في قدرات هؤلاء المتعلمين في هذا الجانب.

الكلمات المفتاحية: متعلمو اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية على المستوى الجامعي، المصطلحات المورفولوجية العامة، مصطلحات تشكيل الكلمة، الكفاءة النحوية.

1. Introduction

Grammar is an essential part of the language system, which can be described in terms of generalizations or scientific standards.

Greek philosophers asserted that grammar was a branch of philosophy linked to the “art of writing,” relating to language structure that includes sentence structure (syntax) and word order (morphology), according to Trask. (2014:18)

In this context, a linguist who specializes in the scientific analysis of grammar is referred to as a “grammarian. ” He states (Ibid) that grammar represents a language’s complete structure, which encompasses phonology, semantics, syntax, morphology, and possibly pragmatics.

Hannounah (2008:1) notes that during the Middle Ages, grammar transformed into a set of rules that prescribed “proper usage,” frequently found in textbooks. However, most linguists contend that grammar should mirror actual usage and outline the principles by which sentences are created and understood. Thus, grammar emerged as a highly valuable tool for enhancing a learner’s skills in their native or foreign language. Until recently, grammar was regarded as a subfield of language study that existed between phonology and semantics, comprising syntax and morphology.

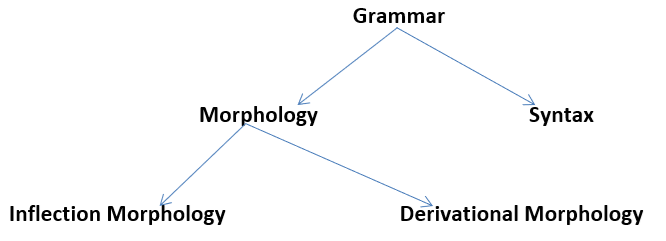

Figure (1): The Main Field of Grammar and Morphology ( Hannounah, 1999:98)

1.2 the Problem of the Study

The issue is that the majority of EFL students have been focusing on the rules of syntax while neglecting the importance of morphology and its guidelines, such as types of morphemes and various allomorphs, as well as other elements like analogous suffixes. This is crucial for foreign learners to aid in the learning process.

1.3 The Significant of the Study

The current study holds significance for lexicography since morphological specifics are necessary and considered alongside entries in the English dictionary.

1.4 the question of the study

This study aims to address the following two questions:

1- To what degree can EFL students identify the correct morphological terms?

2- To what degree can EFL students generate the correct morphological terms?

2.1 Features of modern Grammar

According to Hamash and Abdulla (1968: 8), language and writing are distinct entities, just as sounds and letters are different. Writing serves as a representation of speech, rather than being a language. For instance, writing in English does not fully represent the sounds. This is because letters that aren’t pronounced are utilized to form words, and at times, individuals articulate sounds that are not captured by the letters that are used for writing them. Modern grammar attempts to clarify speech, rather than focusing on letters and spelling. The aim of modern grammar is to describe how speakers of a particular language communicate understandably. In fact, contemporary grammar does not prescribe what people ought to say. Grammar should illustrate patterns instead of rigid rules, and grammatical and ungrammatical expressions rather than right or wrong.

There exist form and meaning (content) in language. Because the latter is mostly a nonlinguistic phenomenon, it is difficult to examine in a scientific manner. On the other hand, it is open to analysis and scientific management. It should be addressed in contemporary grammar as minimally as possible and evaded (lbid:9).

2.2 Grammar meaning and Function

Grammar defined a language’s framework and the formation of sentences from elements such as words and phrases. Typically, it considers the functions and meanings these phrases possess within the linguistic framework. It may or may not encompass the description of the sounds of a language (Richards and Schmidt, 2002: 230). Similarly significant, in Generative Linguistics, grammar articulates the speaker’s understanding of the language. It examines language concerning how it might be organized in the speaker’s cognition, and which principles and parameters are accessible to the speaker during language production (Ibid: 231).

Furthermore, Crystal (1987: 223) defines grammar as “a component of any language,” which implies that because grammar is a part of every language, there cannot be a language without sounds. It represents a segment of language that signifies the way people convey structural meaning. In the example below: The dogs spotted the cat.

(1). The term (the) is a grammatical term since it serves a grammatical purpose.

(2). The sound /s/ in the term (dogs) is, in fact, essentially grammatical because it signifies quantity.

(3). (Dogs) is the term that performed the spotting while (cat) was the one that was spotted.

Consequently, the arrangement of words in this sentence serves as a grammatical characteristic that conveys meaning. The grammar of a language encompasses two components: (1) Morphology and (2) Syntax. In other terms, grammar pertains to all the structural elements that indicate grammatical significance. The approach that explains every grammatical sequence and removes all non-grammatical sequences is the outline of the structure of all grammatical units and expressions.

2.3 Morphology: Definition and Meaning

According to Andrew (2002:32), morphology refers to the branch of grammar that focuses on the composition of words and the connections between them that involve the morphemes that constitute them. In other words, morphology represents the scientific examination of the structures of the words within a language. Richards and Schmidt (2002: 342) assert that morphology encompasses the scientific analysis of morphemes and their various forms (allomorphs) along with the methods by which they come together in word formation. For example, the English word (unfriendly) is created from (friend), the adjective-forming suffix (-ly), and the negative-forming prefix (un-). This means that morphology addresses the structural components of words in a language. The arrangement of these structural components influences meaning; for instance, (friendly) and (unfriendly) convey distinct meanings.

Furthermore, Al Khuli (2009: 55) asserts that morphology is the field of linguistics that focuses on morphemes. It is an aspect of grammar, which encompasses both morphology and syntax. Morphology pertains to the structure of words, while syntax pertains to the structure of sentences.

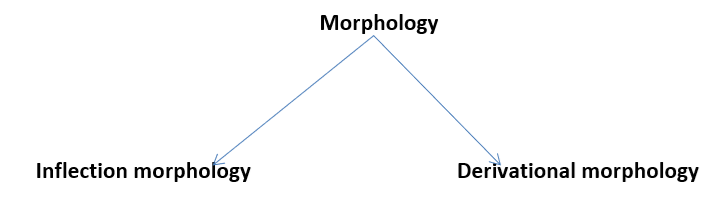

Crystal (2003:301) highlights that morphology is typically categorized into two primary areas of study: (1) Inflectional Morphology and (2) Derivational Morphology. As stated by Hannounah (1999:99), inflectional morphology does not generate or create new words within the English language, meaning it does not alter the part of speech of words. However, it signifies aspects of a word’s grammatical function; for example, it transforms a noun from singular to plural, or changes a verb’s tense from present to past (girls → girls, watch → watched). Inflectional morphemes include (-ing, -s, -er, -est, -ed). They modify a word’s form to convey its connection to other words within a sentence. Conversely, derivational morphology generates or forms new words in the language, functioning to create words of a different grammatical category; in other words, it modifies the part of speech of a word. For instance, when a derivational morpheme (-ure) is appended to the verb (fail), it is transformed into a noun (failure), and adding (-ment) to the verb (punish) changes it into a noun (punishment). Thus, derivational morphemes combine with words in an arbitrary manner and do not restrict the word; that is, multiple derivational morphemes can be added to the end of a word. For example, (nation n. )→(national adj. ) → (nationalize v. ) → (nationalization n. ). Overall, derivational morphology converts an existing word into a new word. The following figure demonstrates the primary fields of morphology:

Figure (2): The Main Field of Morphology ( Hannounah, 1999:98)

2.4 Morphological Terms

Special vocabulary items that are utilized within a certain discipline or subject matter are referred to as terms. Naturally, a term is characterized as “a lexical unit” when it comprises one or more words that convey an idea in a realm of knowledge that is generally nominal, which means:

1. often appearing in writings limited to a specific field, and

2. possessing a specific meaning within a particular domain of knowledge (kageura, 2002:9).

According to Alberts (1998: 1), a term is a visual linguistic depiction of a mental concept and can be categorized into the following types: single term, compound word, phrase, collocation, letter word, abbreviation, etc. She (Ibid. ) states that terms can be utilized as such if the user already has a clear framework of knowledge that defines the function of the term in a structure.

Richards and Schmidt (2002: 544) assert that a technical term is:

1. A term whose use is restricted to a specific area of knowledge and which has a specialized meaning. For example, ‘phoneme’, ‘morpheme’, ‘word’ and ‘syntax’ in the field of linguistics.

2. A general term that possesses a specialized meaning in a particular domain, like ‘matter’ in the realm of chemistry.

2.4.1Morphology

Defined as “the study of forms” in its literal sense (Yule, 2010: 67). He (Ibid) asserts that although the expression was initially applied in biology, it has also come to refer to the type of research that elucidates all of the basic units (elements) in language from the mid-19th century. Technically speaking, these (units) are known as morphemes. Stageberg (1981:83) describes morphology as the term utilized in language to detail the study of a word’s inherent structure. As described by Yule (2010: 67), morphology is the study of language’s fundamental forms.

Looked at from a different perspective, some linguists regard morphology as the scientific study of the principles by which words are created. Fromkin, et al (2017:37) define morphology as the scientific study of the internal structure of words, and of the principles by which words are constructed. This term comprises two morphemes (morph) + (ology). The morpheme (morph) signifies ‘element’ while the morpheme (ology) denotes ‘branch of knowledge’, thus, the meaning of morphology is the branch of knowledge pertaining to (word) forms. In addition, morphology is the linguistic term that refers to our internal grammatical understanding of the words of our language.

2.4.2 Morpheme

Hannounah (1999: 95) describes morpheme as the terminology utilized in morphology to denote the fundamental unit of grammatical structure. She (Ibid. ) notes that a morpheme represents the smallest unit of grammatical function or meaning, meaning the least meaningful unit in a language; for example, the English term reopened in the phrase The experts reopened the investigation of the lost animal, which includes three morphemes, namely open (a minimal unit of meaning), re- (a minimal unit of meaning), and -ed (a minimal unit of grammatical function that indicates past tense). Morphemes are categorized into two different types: (1) Free Morpheme: These are the morphemes that possess distinct meanings, such as study, write, exam, etc. In general, free morphemes are seen as the collection of separate English forms, and (2) Bound Morpheme: These are the morphemes that typically cannot exist independently with a distinct meaning, but are affixed to another form, such as -ist, -er, re-, -ed, and -s (bound morphemes are primarily affixes).

Richards and Schmidt (2002: 341) describe a morpheme as the term that signifies the smallest meaningful unit within a language. This means that a morpheme cannot be split without altering or eliminating its meaning; for instance, the English term nice is a morpheme. If the n is taken away, it becomes ice, which conveys a different meaning. They (Ibid. ) assert that certain English terms are composed of just one morpheme, such as read, write, nice, exam, and book. Conversely, some words have multiple morphemes; for example, the English word unkindness is made up of three morphemes: the root kind, the negative prefix un-, and the noun-forming suffix -ness. Morphemes can serve grammatical roles; for example, in English, the -s in She talks a lot is a morpheme that serves a grammatical purpose.

Moreover, Trask (2003: 300) describes morpheme as the term that denotes the smallest distinctive unit of grammar, and the primary focus of morphology. Equally important, Stageberg (1981: 83) contends that morpheme is the term that signifies a brief segment of language. He (Ibid. ) asserts that:

1. The morpheme is a word or a portion of a word that conveys meaning.

2. The morpheme cannot be separated into smaller meaningful units.

3. The morpheme appears in various verbal contexts with a relatively consistent meaning. For example, the English word straight satisfies the previously mentioned criteria since it conveys meaning, it cannot be split into smaller meaningful components, and it can appear in various verbal contexts with a relatively consistent meaning, e. g. , straightedge and straighten; manage also fulfills the earlier criteria because it conveys meaning, it cannot be divided into smaller meaningful segments, and it can appear in different verbal contexts with a relatively stable meaning, e. g. , manageable and manageability.

Furthermore, Fromkin et al (2017: 54) assert that a single word can consist of one or more morphemes:

One Morpheme: boy, desire, meditate

Two Morphemes: boy + ish = boyish, desire + able = desirable, meditate + tion = meditation

Three Morphemes: boy + ish + ness = boyishness, desire + able + ity = desirability

Four Morphemes: gentle + man + li + ness = gentlemanliness, un + desire + able + ity = undesirability.

More than four Morphemes: un + gentle + man + li + ness = ungentlemanliness, anti + dis + establish + ari + an + ism = antidisestablisharianism. They (Ibid. ) contend that a morpheme may be represented by a single letter such as the morpheme ‘a-‘ (meaning without), e. g. , amoral and asexual, or by a single syllable, e. g. , child [tʃaild] and ‘-ish’ in childish [tʃaildif]. A morpheme can also be made up of two syllables, for example, camel [kaml], lady [leidi], water [wo:tə], or consist of three syllables, such as Hackensack [hakinsak], crocodile [krokədail], or of four syllables, like hallucinate [həlusineit], helicopter [helikoptə]. Consequently, a morpheme, which is a linguistic unit, is an arbitrary combination of a sound and a meaning (or grammatical function) that cannot be broken down further. Equally significant, Hamash and Abdulla (1968) suggest that a morpheme may be composed of one or more phonemes; in this context, the phoneme is a non-meaningful unit while the morpheme possesses lexical meaning, the field that examines these small meaningful units (morphemes) is referred to as morphology.

2.4.3 Word

Defined One of the most essential elements of language structure is the word.

Individuals speak single words such as “no,” “mind,” and “mammy” during their initial language acquisition as children, and they must learn hundreds of words to communicate in our original language fluently. By the age of 17, it is estimated that native speakers of a language know approximately 80,000 words, as stated by Miller and Gildea (1987: 231). This collection of words for any language, while not exhaustive, is known as its ‘lexicon’ (Hannounah, 1999: 103).

Equally significant, the most accurate definition of word is provided by Leonard Bloomfield (1933: 243), who defines word as “a minimum free form,” meaning the smallest unit that can stand alone and convey meaning. However, this definition does not hold true for every language or every type of word. According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 588), a word is the smallest linguistic unit that can function independently in speech or writing. Additionally, Hannounah (1999: 103) asserts that a word is linked to different types of information:

1. Phonetic / Phonological Information: For every word that individuals know, they possess knowledge of its pronunciation; in other words, being familiar with the word repeat involves knowing a specific arrangement of sounds [ri’pi:t].

2. Morphological Information: For each word that individuals have acquired, they inherently understand something regarding its internal composition. For example, our instincts indicate that the word tree cannot be broken down into any significant segments. Conversely, the word trees is made up of two components: the word tree (1st morpheme) + {-s plural} (2nd morpheme).

3. Syntactic Information: For every word that individuals learn, they comprehend how it integrates into the overall framework of sentences in which it can be employed. For instance, we recognize that the word write can be utilized in a sentence like Yousuf always writes short stories; whereas the word readable can be employed in a sentence like This book is readable. Certainly, native speakers instinctively and subconsciously understand how to incorporate words into sentences.

4. Semantic Information: For each word that individuals are familiar with, they have acquired one or multiple meanings. For example, to understand the word sister means to recognize that it signifies a specific meaning (a female sibling).

5. Pragmatic Information: For every word that individuals learn, they are aware not only of its meaning or meanings but also of how to employ it within the context of discourse or various situations. For instance, the word brother can denote not merely ‘a male sibling’ but can also serve as a conversational interjection in ‘Oh brother! ‘ What a mess!

According to Yule (2010: 500), the term word is a linguistic concept denoting a unit of expression that possesses universal intuitive acknowledgment by native speakers, in both oral and written forms. In other words, a word is a fundamental component in the two primary facets of language: the spoken and written aspects, where it plays a crucial role in language communication.

2.4.4 stem

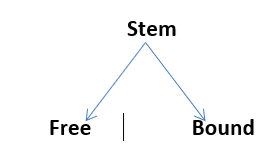

According to William (1972: 129), the term stem refers to the grammatical name for the primary word form that is combined with other bound morphemes; it is also referred to as “the basic morpheme. ” Additionally, Hannounah (1999:97) views stem as the designation that pertains to any segment of a word regarded as a unit to which an operation can be applied, for example, when one adds an affix to a stem or that fundamental morpheme in a word that conveys the principal meaning. For example, in the English term unhappy, the base form (stem) is ‘happy’, the base form (stem) in the word ‘treatment’ is ‘treat’, the base form (stem) in the word ‘examination’ is ‘exam’, the base form (stem) in the word ‘unhappiness’ is ‘happy’, and so forth (Ibid. ). She (Ibid:98) states that the base morpheme (stem) is categorized into two types: (1) free base morpheme (free stem), and (2) bound base morpheme (bound stem). In reality, in English, there are numerous words in which the element is not actually a free morpheme. The following figure depicts the two types of stems.

Figure (3): Types of stem( Hannounah, 1999:97)

Concerning the two types of stems, the majority of stems in English are free morphemes. For example, the term ‘readability’ contains the free morpheme (free stem) ‘read,’ which can exist independently, conveying the main meaning of the word, while ‘dress’ in the English term ‘undressed’ is the free morpheme (free stem) of that word. Conversely, a bound stem is characterized as a morpheme within a word that signifies the stem but to which it is difficult to attach a specific or clear meaning (i. e. , it cannot exist independently as a separate word with meaning, e. g. , (-ceive) in the English term ‘receive’ and (-peat) in the English term ‘repeat’ (Ibid: 99).

Furthermore, Al-Khuli (2009: 62) establishes a clear differentiation between root and stem, asserting that when all affixes are stripped from a word, what is left is referred to as the root. This can be represented formally as follows: Word – Affixes = Root (The roots of ‘internationalization’, ‘reviewing’, ‘returnable’, and ‘re-evaluation’ are nation, view, turn, and value, respectively). Conversely, the definition of stem is distinct from that of root. The stem is the base word to which the affix is attached. The following equation can be used to encapsulate the aforementioned explanation: Word – Last Affix = Stem (The stems of ‘internationalization’, ‘reviewing’, ‘returnable’, and ‘re-evaluation’ are internationalize, review, return, and re-evaluate, respectively). Consequently, the stem may either be a root or a root in conjunction with affixes. The root of ‘mightiness’ is might, while the stem is mighty. The root of ‘greatness’ is great, and the stem is likewise in this regard (Ibid. ).

According to Yule (2010: 295), a stem is described as a grammatical term that signifies the base form to which affixes are added during the word formation process. In other words, the stem is a primary focus for morphologists who create words by attaching affixes to a stem. Furthermore, Richards and Schmidt (2003: 513) view ‘stem’ as the terminology used in morphology to denote a segment of a word to which an inflectional affix is connected. For instance, in English, the inflectional suffix (-s) can be appended to the stem college → colleges to express the plural form. They (Ibid: 514) also assert that the stem of a word might be:

1. a root combined with a derivational affix, for example, teach + er = teacher, drive + er = driver, act + or = actor.

2. two roots, such as text + book = textbook, work + shop = workshop texts. Therefore, we can express: text + s (worker + er) + s = workers, (work + shop) + s = workers, (work + shop) + s = workshops (Ibid. ).

2.5 Word- Formation Terms

According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 589), it is characterized as the morphological term that describes the method a language employs to generate new words. In other words, certain morphological processes can lead to the formation of new words. The fact is that an individual can understand a new word in their first language and manage the usage of various forms of it. For instance, even if someone had never encountered or seen the word “somp,” they would likely have no difficulty understanding the grammatical meaning of other new words formed from it, such as somps (noun), somping (verb), and sompist (noun) (Hannounah, 1999: 104). To put it differently, new words in a language are formed by processes that can be articulated by its speakers.

Crystal (2003: 502) describes word-formation as the concept that encompasses the entire process of morphological variation in the makeup of words, meaning it includes the two primary areas of inflection (word variation for denoting grammatical relationships) and derivation (word variation that indicates lexical relationships). Indeed, in a more exact sense, word-formation pertains solely to the latter process, which can be further categorized into:

(1) compound word-formation, such as blackbird being created from the free units (elements) black + bird, and

(2) derivational word-formation, for instance, national → nationalize → nationalization is formed through the addition of the bound elements (-al), (-ize), and (-ation). According to Trask (2003: 240), word-formation is the term applied in morphology to refer to the methods used to generate new lexical items within a language. In English, these methods consist of back-formation, blending, derivation, and compounding. In fact, some of these methods change the meaning of the word, while others modify the word’s part of speech.

2.5.1 inflection

Defined as the term utilized in morphology to identify one of the two word-formation processes (the other being derivation). Since inflectional morphemes do not change the grammatical category of the roots to which they are attached, they act as indicators for grammatical connections such as plural, past tense, and possession. For instance, the words travel, travels, and travelled create a unified paradigm. When a word is modified for the past tense, plural, etc. , it is described as such. This was the interpretation of the term “accidence” in traditional grammatical studies (Crystal, 2003: 233). As noted by Richards and Schmidt (2002: 257), inflection is the grammatical term that pertains to the process of adding an affix (“always suffixes” Al Khuli, 2009: 59-60) to a word or altering it in another manner based on the grammatical rules of a language. For example, in English, verbs are inflected for third-person singular: I always help them, he/she always helps them, and for past tense: I helped them yesterday, he/she helped them yesterday. The majority of nouns can be inflected for plural forms: house» houses, book» books, examination» examinations, man» men.

According to Yule (2010: 69), inflection discloses aspects of a word’s grammatical role rather than forming new words in the language. Words can be recognized as singular or plural, in the past tense, past participle tense, or present tense, in the comparative or superlative degree, and whether or not they are in the possessive form by employing inflectional morphemes. Inflectional morphemes are consistently suffixes, according to Al Khuli (2009: 59–60), and they do not change the root class.

Stageberg (1981: 92) asserts that the inflectional affixes in English can be represented as follows:

|

Inflection Affix |

Examples |

Name |

|

|

1- |

{ – s} |

Cats , Children , Sheep |

Noun plural |

|

2- |

{ – s} |

Book’s ,Engineer’s |

Noun singular possessive |

|

3- |

{ – s} |

Children’s , Women’s |

Noun plural possessive |

|

4- |

{ – s} |

Walks , Plays |

Present Third person singular |

|

5- |

{- ing} |

Walking , Playing |

Present participle |

|

6- |

{ – ed} |

Played ,Studied |

Past Tense |

|

7- |

{ – ed} |

Played , Taken |

Past participle |

|

8- |

{ – er} |

Faster ,Bigger, Happier |

Comparative |

|

9- |

{ – est} |

Fastest, Biggest ,Happiest |

Superlative |

Table (1): Inflection Affixes

2.5.2 Derivation

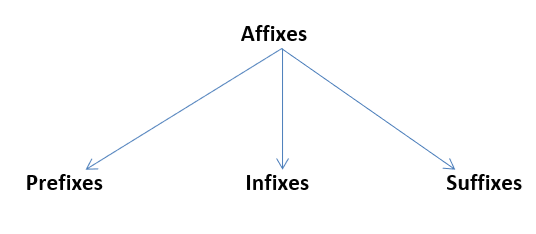

Described as the morphological term that best represents the process of forming new words in contemporary English, or word formation. Numerous small characters, or components, of the English language are utilized in the derivation process and are usually listed separately in the English dictionary. However, these characters (components) are referred to as ‘affixes’ such as un- in unhappy, -ful in joyful, -ish in boyish, and pre in prejudge (Hannounah, 1999: 107). The following figure demonstrates the types of affixes used in derivational morphology.

Figure (4): Types of Affixes Used in Derivational Morphology( Hannounah, 1999:108)

Trask (2003: 67) indicates that the term “derivation” in morphology signifies the method of forming new words from existing ones by adding suffixes; for instance, the words “historical” and “prehistory” are formed from “history. ” As he mentions (Ibid. ), derivational morphology refers to the sector of morphology that focuses on generating words (lexical items) by attaching prefixes or suffixes to other words. For example, rewrite is formed from ‘write’ and booklet is formed from ‘book. ‘ Furthermore, Stageberg (1981: 94) mentions that derivational suffixes comprise all suffixes that are not inflectional. The attributes of these morphological suffixes are:

1. The words that derivational suffixes merge with are a random matter. For example, to form a noun from the verb ‘establish,’ ‘ment’ has to be added» establishment, whereas the verb ‘fail’ becomes a noun only when it unites with ‘ure’» failure. This indicates that the process is random. The subsequent examples clearly demonstrate this randomness:

discover (verb)» discovery (noun)

compose (verb)» composition (noun)

2. In numerous instances, a derivational suffix alters the grammatical category of the term to which it is affixed; for example, the verb ‘repeat’ transforms into a noun with the addition of ‘ition’ → repetition, while the noun ‘act’ shifts to an adjective through the inclusion of ‘-ive’ → active.

3. Derivational suffixes typically do not finalize a word, meaning that after a derivational suffix, one can occasionally attach another derivational suffix and frequently add an inflectional suffix. For example, to the word ‘fertilize’, which concludes with a derivational suffix, another derivational suffix must be appended, ‘-er’ → fertilizer, and the inflectional suffix ‘-s’ can be included, finalizing the word → fertilizers.

Furthermore, derivational morphemes demonstrate clear semantic value, as stated by Fromkin et al. (2017: 121). They are similar to content words in this respect, although they do not function as words. A base assumes meaning when a derivational morpheme is added. Furthermore, the derived word may fall under a different grammatical category compared to the original word, as shown by suffixes like ‘-able’ and ‘-en’; when a verb receives the suffix ‘-able’, it transforms into an adjective, exemplified by ‘desire’ (verb) + ‘-able’ = ‘desirable’ (adjective), and when the suffix ‘-en’ is attached to an adjective, a verb is created, as in: ‘dark’ (adjective) + ‘-en’ = ‘darken’ (verb).

2.5.3 Affixing

Affixes constitute a type of bound morpheme, which refers to the collective term for the formative types that can only be used when combined with another morpheme (stem). A language possesses a limited number of affixes. They are usually categorized into three types based on their position in relation to the stem of the word: the affixes that are added at the beginning of a root or stem are labeled as ‘prefixes’, for instance, unhappy, unimportant, dislike; the affixes that come after a stem are known as ‘suffixes’, such as happiness, readiness, boyish, foolish; and the affixes that appear within a stem are termed ‘infixes’ (Fromkin et al, 2017:15). In addition, other languages often feature the third type of affixes, or “infixes,” unlike English. This term refers to an affix that is embedded within a word structure. For instance, the infix “-rn-” is inserted into verbs in the language “Kamhmu,” which is spoken in South-East Asia, to create corresponding nouns. For example, “to eat with a spoon” (hip v. ) → hrniip n. , which signifies “spoon” (Hannounah, 1999: 108).

Trask (2003: 9) characterizes an affix as a term in morphology that signifies a small unit of grammatical material which cannot exist independently but must be attached to another element within a word. For example, the ‘-er’ in rewrite, the ‘-ness’ in readiness, and the plural marker ‘-s’ as seen in books. He (Ibid. ) further states that an affix is typically a single morpheme and is certainly a bound morpheme. This means that although affixes possess grammatical meaning and function, they are unable to stand alone in a language.

2.5.4 Compounding

Defined as a term used in phonology that refers to the process of combining two independent words to create one form, in fact, this compounding process is frequently applied in German and English, though it is less prevalent in French and Spanish. The English language is filled with many compound words, such as text + book → textbook, sun + burn → sunburn, wall + paper → wallpaper, and numerous others (Hannounah, 1999: 106). However, compounding is characterized by Richards and Schmidt (2002: 98–9) as the morphological term used in morphology to explain a fusion of two or more words that function as a singular word. For instance, the compound adjective “self-made” in the sentence that follows: He was an independent man. Compound words can be composed as two separate words, like police station, or as a single word, like headache, or hyphenated, like self-government.

Al-Khuli (2009: 71) characterizes compounding as a morphological concept utilized to explain the processes of merging two words to create a new word. The compounding process can manifest in various ways:

1. Noun + Noun = Noun, for example,

table + cloth = tablecloth

foot + ball = football

rain + bow = rainbow

class + mate = classmate

2. Adjective + Adjective = Adjective, for example,

icy + cold = icy-cold

red + hot = red-hot

bitter + sweet = bittersweet

3. Noun + Adjective = Adjective, for example,

water + tight = watertight

life + long = lifelong

4. Verb + Noun = Noun, for example,

pick + pocket = pickpocket

dare + devil = daredevil

5. Adjective + Noun = Noun, for example,

black + board = blackboard

poor + house = poorhouse

white + board = whiteboard

6. Adjective + Verb = Adjective, for example,

high + born = highborn

7. Noun + Verb = Verb, for example,

spoon + feed = spoon-feed

brain + wash = brainwash

day + dream = daydream (Ibid. )

Compounding is a linguistic term

utilized to create a word by merging two or more smaller words together, like redhead,hatchback, scarecrow, overthrow, forget-me-not, five-pound-note (Trask, 2014: 49).Some compound words, such as blue-eyed → (-ed) and overrepresented → (-ed), include an additional affix. Nevertheless, as per Crystal (2003: 92), the term “compounding” is often used in descriptive linguistic research to refer to linguistic units comprised of elements that function independently in various contexts. Compounding appears in compound words, such as bedroom, washing-machine, rainfall, which contain two or more free morphemes.

According to Yule (2010: 85), compounding is the morphological term for the process of combining two distinct words to create a new word, for example, water + bed = waterbed.According to He (Ibid), compounding refers to a technical term utilized in morphology, or the method of combining two distinct words to form a single entity. Therefore, in German, lehn and wort are merged to produce lehnwort. The compounding method is frequently used in many languages, such as English and German, although it is considerably rarer in languages such as Spanish and French. For example,

Waste + basket = wastebasket

Book + Case = Bookcase

Print + finger = fingerprint

Print + paw = paw-print

2.5.5 Borrowing

Defined as the morphological term for the process through which a word from one language is taken into another. For example, numerous words in English have been adopted from other languages; for example, the word “castle” originates from Norman French, “ballet” is derived from Modern French, “vanilla” comes from Spanish, “soprano” has roots in Italian, and “kayat” is sourced from Modern French. Such borrowed words are known as ‘Loan words’ (Trask, 2014: 31). Moreover, as per Crystal (2002: 56), borrowing is a notion in comparative and historical linguistics that recognizes a linguistic form that a language dialect has acquired from another language; these words are typically referred to as “loan words,” such as restaurant, bondomie, and chagrin, which are English words that have their origins in French.

According to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 56–57), a term or expression that has been taken from one language and used in another is called borrowing. For instance, the English language has borrowed the Italian term “al fresco” (meaning in the open air) and the American Indian word “moccasin,” which referred to “a type of shoe. ” Furthermore, they indicate that native English speakers attempt to pronounce borrowings in the way they are articulated in their original languages. However, most native English speakers pronounce borrowed words and phrases following the English Sound System if those terms are commonly used. For example, the French word garage [garaʒ] becomes [gaera:ʒ] or [gærid3] in British English; however, American English keeps some elements of the French pronunciation.

According to Harman and Stork (1972:231), borrowing ranks among the most frequent sources of new vocabulary in English. It pertains to the adoption of words from different languages. Throughout English language history, many ‘loan words’ (borrowed words) have been embraced from both European and Asian languages, including alcohol from Arabic, boss from Dutch, piano from Italian, and yogurt from Turkish. Likewise, other languages tend to borrow expressions from English, as seen in the Japanese use of suupaamaaketto, which translates to ‘supermarket,’ or in the Hungarian context where they refer to ‘sports’ as klub for ‘club’ and futbal for ‘ football ‘.

2.5.6 coinage

According to Hannounah (1999: 105), the term “coinage” in morphology pertains to one of the less common morphological processes in English word-formation. It signifies the generation of entirely new vocabulary. Though aspirin, nylon, and Kleenex were initially utilized as brand names, they are presently recognized words in the English language. According to Trask (2014: 150), coinage is a linguistic term that refers to a newly created word, such as geopathic, internet, or CD. In other words, new terms need to be invented in the language due to progress in science, technology, and evolving requirements in everyday life. Coinage, as described by Yule (2010: 285), is “the creation of new terms in the language,” like Xerox. The most notable origins are the names devised for new products that are used as terms for all variations of a product in the market. Aspirin, nylon, Vaseline, and zippers are older instances. Likewise, contemporary English coinages comprise Xerox, Teflon, Granola, and Kleenex. The typical origins of coinage consist of novel ideas, products, and human activities (Yule, 2010:5).

2.5.7 Back -Formation

Back-formation, as explained by Bollinger (1968: 210), is a particular form of reduction process where a word of one type—usually a noun—is modified to produce another word of a different type—usually a verb. The verb televise was created from the noun “television,” which first came into use. This serves as a typical example of back-formation. Additional examples include edit, which is derived from ‘editor’, emote, which comes from ’emotion’, and opt, which originates from ‘option’.

Richards and Schmidt (2002:45) characterize back-formation as a morphological concept that outlines a method of word-formation achieved through the removal of an affix from an existing word. For instance, the verbs televise, peddle, and babysit have been created by native English speakers from the words ‘television’, ‘peddler’, and ‘babysitter’, respectively. Moreover, the most prevalent method for producing new words is by combining existing words with new ones.

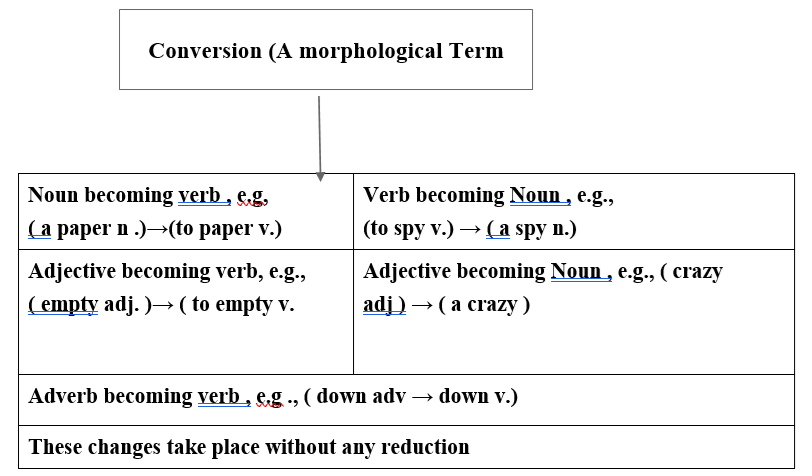

2. 5. 8 conversion

As stated by Nasr (1980: 223), conversion is a morphological phrase that denotes alterations in a word’s grammatical role, such as when a noun changes into a verb without any reduction. It is also referred to as a ‘functional shift’ or ‘category change’. For example, the sentences below utilize the nouns butter and paper as verbs:

1. She has buttered the toast.

2. Sami papered the bedroom walls last month.

According to Hannounah (1999: 107), conversion is seen as a constructive process in Modern English and signifies the change of verbs into nouns, such as guess, must, and spy → a guess, a must, and a spy, respectively. Adjectives such as dirty and empty also convert into verbs: to be dirty, to be empty; in the same vein, adjectives like crazy and nasty become nouns: to be a crazy and a nasty. Furthermore, in different forms, adverbs like up and down change into verbs as demonstrated in the examples that follow:

1. The archaeologists upped the pieces of the statues in 1997.

2. The workers downed the boxes of apples yesterday.

The following figure represents the morphological processes of conversion in English.

Figure (5) : The process of conversion in English Morphology, adopted From Hannounah, 1999: 107)

Additionally, Yule (2010: 285) clarifies that conversion is a term in linguistics that refers to the process of changing a word’s role, such as a verb turning into a noun, an adjective transforming into a noun, or a noun becoming a verb, in order to generate new words. This phenomenon is also called “category change” or “functional shift. ” For instance, vacation (noun) → vacation (verb), as illustrated in the subsequent sentence: She is vacationing in Texas. According to Trask (2014:56), conversion is defined as a morphological process that outlines a linguistic shift where a word is moved, without modification or addition, from one part of speech to another. English often employs conversion. For example, the noun access can be used as a verb in the sentence: Many scientific facts can be accessed from these books; the adjective brown can function as a verb in the sentence: The worker must brown the meat; and the verb “drink” can take on the role of a noun in the sentence: He had a quick drink.

2. 5. 9 Acronym

An acronym is a linguistic term that refers to the method through which specific new words are formed from the initial letters of a set of other words, as noted by Hannounah (1999: 107). An acronym typically consists of capital letters. For instance, UNICEF is an acronym for the ‘United’ Nations Children’s Fund’, while NATO represents the ‘North Atlantic Treaty Organization’. However, some acronyms can also lose their capitalization and evolve into common words. For instance, radar is an acronym derived from ‘Radio Detecting and Ranging’. Significantly, as stated by Yule (2010: 282), an acronym is a linguistic concept that describes a new word created by merging the starting letters of other words. For instance, the expressions United States and ‘The United States of America’ produce the terms ‘United Nations’ and U. S. A.

An acronym, according to Al-Khuli (2009: 71), is a morphological concept that signifies a word constructed from the initial letters of other words in the same language. For example, the term UNESCO was created from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’, while the term UNO is derived from ‘United Nations Organization’. Similarly, acronyms are grammatical concepts that pertain to words formed from the initials of the phrase they signify, such as I. P. A. , which stands for ‘International Phonetic Association’ or ‘International Phonetic Alphabet’, according to Richards and Schmidt (2002: 8).

2. 5. 10 Blending

According to Yule (2010: 284), blending is a morphological concept that defined the procedure of merging the start and finish of two words to create a new term. For instance, brunch is produced by combining the terms ‘breakfast’ and ‘lunch’. The notion of blending in morphology pertains to the action of attaching the beginning of one word to the ending of another for the purpose of merging two separate forms into a unified expression. For example, ‘smoke and fog’ come together to produce smog, ‘motor and hotel’ merge to create a motel, and ‘television and broadcast’ join to form telecast. However, Trask (2014: 30) states that blending is a linguistic term for a word generated by connecting segments of different words. Instances of such terms include Oxbridge (Oxford + Cambridge), guesstimate (guess + estimate), and smog (smoke + fog). The term ‘blending’ is discussed in morphology by Richards and Schmidt (2002: 55) to refer to a relatively ineffective method of word formation whereby new words arise from the beginning (typically the first phoneme or syllable) of one word and the ending of another; for example, ‘volcano and fog’ is the basis for the creation of the term vog.

2. 5. 11 clipping

According to Crystal (1985: 121), clipping is a morphological term used in language that refers to the shortening of a multisyllabic word into a more concise form. For instance, the transformation of ‘gasoline’ to gas and the clipping instances of ‘professor’ to prof, ‘advertisement’ to ad, and ‘laboratory’ to lab. Additionally, according to Trask (2014: 43), clipping is a linguistic concept that results from removing a segment of a longer word or phrase, typically one that retains the same meaning. For example, the word gym is derived from ‘gymnasium’, flu is derived from ‘influenza’, phone is derived from ‘telephone’, net is derived from ‘internet’, and sitcom is derived from ‘situation comedy’. He (Ibid. ) asserts that a clipped form is a valid word as opposed to an acronym. Likewise, Yule (2010: 284) describes clipping as the act of shortening a multisyllabic word into a more concise version, such as ad from ‘advertisement’.

3. Test Design

In both applied linguistics and theoretical linguistics, the goal of tests created by teachers and researchers is to assess the learners’ performance in a specific linguistic domain. As a result, the researcher developed a two-part questionnaire, with the first section containing ten items, each offering four options from which the test-taker must select the correct linguistic term that corresponds to the question posed, a method that Aljuboury (2014: 56-7) refers to as “a close-ended test. ” The second part of the questionnaire, intended to evaluate the learners’ knowledge, also consists of ten items with blank spaces to be filled in with an appropriate linguistic term.

The current test can be seen as an achievement test since it measures a learner’s long-term learnability, as Harrison(1983: 7) suggests. To carry out this measurement, the questionnaire in question consists of two types of terms: General Morphological Terms and Word-Formational Terms. In the recognition section, items (1), (2), and (3) correspond to the general morphological terms and are designed to assess the learners’ recognition skills in the following areas: morphology, morpheme, and word, respectively, while the remaining items, (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), and (10), represent the word-formation terms and aim to evaluate the Iraqi EFL college learners’ recognition competency in the following categories: inflection, suffixing, acronym, conversion, borrowing, back-formation, and blending, respectively. The second section of the questionnaire, the production question, seeks to determine the Iraqi EFL college students’ proficiency in morphological terms by writing the correct linguistic term that corresponds to what is requested. In this context, items: (4), (9), and (10) denote the general morphological terms: stem, word-formation, and morphology, respectively, whereas the other items of the question: (1), (2), (3), (5), (6), (7), and (8) represent the word-formation terms: inflection, conversion, compounding, coinage, affixing, clipping, and back-formation, respectively.

After creating the questionnaire for the current study, one hundred third-year students from the Department of English, College of Education for Human Sciences, Al Muthanna University, Iraq, are randomly selected as a representative sample of Iraqi EFL college students. The test items are chosen with great precision to encompass the morphological terms. Furthermore, the wording of the test items is done with utmost care and focus to ensure that ambiguity is entirely eliminated. Consequently, the test items require no more than a single response (Ibid: 20).

4. Discussion and Results

Upon gathering the data representing the examinees’ responses, it is clear that the learners encounter significant challenges when addressing the items included in the questionnaire of the present study. The subsequent data table illustrates the students’ poor performance in the recognition portion.

|

Iraqi EFL college learners Recognition in Morphological Terms |

|||||

|

Question items |

Morphological Terms |

Correct Responses |

Percentage |

||

|

General Morphological Terms |

|||||

|

1 |

Morphology |

90 |

90% |

||

|

2 |

Morpheme |

86 |

86% |

||

|

3 |

Word |

82 |

82% |

||

|

Total |

3 |

258 |

Average 86% |

||

|

Word Formation Terms |

|||||

|

4 |

Inflection |

58 |

58% |

||

|

5 |

Suffixes |

53 |

53% |

||

|

6 |

Acronym |

26 |

26% |

||

|

7 |

Conversion |

55 |

55% |

||

|

8 |

Borrowing |

36 |

36% |

||

|

9 |

Back-Formation |

38 |

39% |

||

|

10 |

Blending |

35 |

35% |

||

|

Total |

7 |

301 |

Average 43% |

||

|

Totals |

10 |

559 |

Average totals 55.9% |

||

Table (2) : lraqi EFL University learners Recognition Achievement in Morphological Terms.

As evidenced by Table (2) and depicted in Figure (7), the performance of Iraqi EFL college students in recognizing morphological terms is significantly constrained. Item (1), which defines one of the most crucial linguistic terms in morphology, is anticipated to demonstrate exceptional success from the examinees as it pertains to the definition of morphology. As noted by Fromkin et al (2017), it reveals (74%) of the correct responses. Regarding item (2), which necessitates the general morphological term ‘morpheme’, it exhibits (64%) of the correct answers, indicating that Iraqi EFL college learners possess a solid understanding of this fundamental morphological term since this concept is not new to the linguistic knowledge of EFL college students.In this regard, Hannounah (1999) states that a morpheme is “the basic unit of the grammatical structures. ” Many linguists, including Schmidt (2002), contend that learners are more engaged with fundamental concepts than with secondary ones. Concerning the word, which is represented in item (3), it is a term that (57) EFL college students who responded to this item correctly found easy to access; thus, they are able to differentiate it from morpheme, allophone, and phoneme, as asserted by Miller and Gildea (1987). It is assumed to have no relation to acronym, borrowing, and blending, which are presented in items (6), (8), and (10), respectively, and pose a significant challenge for students’ correct responses, indicating that these grammatical terms ought to be included in the textbooks of secondary schools in Iraq and provided with more details and exercises. It is noteworthy that item (6) indicates that EFL learners at issue made (77) incorrect responses regarding the acronym term.The cause of this weak performance may be linked to the fact that the morphological term ‘acronym’ is employed in various organizations such as government institutions, the military, and large commercial corporations (Stageberg, 1981). Furthermore, Pyles (1972: 330) addresses the challenges of acronyms by stating that they are not always easy to identify, particularly for learners who are not sufficiently familiar with scientific inventions, manufacturers’ names, or the history of naming. Conversely, items (4), (5), and (7), which are designed to examine the morphological terms: inflection, suffixing, and conversion, respectively, demonstrate slightly better performance; item (4), which is specifically aimed at assessing inflection, shows a (52%) rate of correct answers, suggesting that roughly half of the learners can answer this item correctly. Item (5), which records (50%) of the correct answers, is also regarded as a successful item in the performance of EFL college learners simply because suffixes are given greater emphasis and clear examples in the textbook devoted to the 2nd year students ‘An Introductory English Grammar (Stageberg, 1981: 89-92). Item (7) which is connected to the morphological concept of conversion shows (51) correct responses (out of 100) as conversion is quite prevalent in English (Trask, 2014). Item (9) which assesses back-formation discloses a significant challenge (31%) in the correct responses within the EFL college students’ performance mainly due to the fact that the learners involved are not familiar with this linguistic term.

Furthermore, the recognition performance of EFL college learners in the General Morphological Terms under examination: morphology, morpheme, and word (56. 66%) of the correct answers is superior to their recognition performance in the Word-Formation Terms associated with the current study: inflection, suffixing, acronym, conversion, borrowing, back-formation, and blending (38. 71%) of the correct answers, suggesting that EFL college students can grasp the general concepts of morphology easily since they are the fundamental terms of morphology, as Hamash (1968) claims.

The findings presented in Table (2) and Figure (7) also indicate that the most challenging morphological terms (acronym and back-formation, borrowing, blending) represented in items (6), (9), (8), and (10), respectively, which range between (23) and (32) correct answers, are lower on the learning scale than the other set of items (4), (5), and (7), which represent the morphological terms inflection, suffixes, and conversion, respectively. This result may be due to the fact that not all morphological terms follow a systematic or regular pattern (i. e. , many of them are irregular and rely on memorization). Bauer (1983: 4) contends that irregular cases are considered to be outside the realm of rules and are instead memorized explicitly. Transitioning to the production section of the questionnaire, the scenario is entirely different when examining the results obtained by the examinees, as shown in Table (3) and illustrated in Figure (8) below.

|

Iraqi EFL college learners Recognition in Morphological Terms |

|||

|

Question items |

Morphological Terms |

Morphological Terms |

Correct Responses |

|

General Morphological Terms |

|||

|

4 |

Stem |

62 |

62% |

|

9 |

Word_ Formation |

58 |

58% |

|

10 |

Morphology |

78 |

78% |

|

Total |

3 |

198 |

Average 66% |

|

Word – Formation Terms |

|||

|

1 |

Inflection |

61 |

61% |

|

2 |

Conversion |

69 |

69% |

|

3 |

Compounding |

30 |

30%. |

|

4 |

Coinage |

58 |

58% |

|

5 |

Affixing |

59 |

59% |

|

6 |

Clipping |

33 |

33% |

|

7 |

Back- Formation |

26 |

26% |

|

Total |

7 |

336 |

Average 48% |

|

Totals |

10 |

534 |

Total |

Table (3): lraqi EFL University learners production Achievement in Morphological Terms

Indeed, there exists a genuine issue with the learners who complete this section of the questionnaire. Item (10), which is designed to draw out from the EFL college learners in question one of the overarching morphological concepts, ‘morphology’, shows a rate of (69%) for correct answers. This is attributable to the reality that all EFL college learners, including the learners being examined, are evidently familiar with the definition of morphology as Al Khuli indicates that morphology is explained as a “branch of linguistics” that concerns itself with word structure.

Moving to item (9), which aims to identify the morphological term word-formation as one of the primary concepts in morphology, reveals (52) correct answers (out of 100) achieved by the testees. This can be attributed to the observation that learners show more interest in outer circle concepts than in those from the inner circle, as noted by Garman (1990). Items (3) and (8), which are intended to assess the word-formation terms: ‘compounding’ and ‘back-formation’, record only (20) and (19) correct responses, respectively. In this context, the learners involved appear to be uncertain regarding the morphological processes pertaining to these two terms. Moreover, the poor results achieved by the learners regarding the aforementioned items necessitate that college instructors provide comprehensive explanations on these topics (compounding and word-formation), as highlighted by many linguists, including Hannounah (1999), who emphasizes the importance of these two concepts in English morphology. Item (5), which is meant to evaluate an essential word-formation term ‘coinage’, indicates that more than half of the learners in question are able to respond correctly. All EFL learners, including those being examined, show interest in the new terms and names associated with emerging technological products like internet, satellite, cellphone, as noted by Yule (2010). Regarding item (7), which discusses the ‘clipping’ morphological term, the low marks (22%) of correct answers from Iraqi university learners illustrate their inadequate linguistic capability in terms of production. This issue needs to be tackled, and the productive skills of EFL college learners must be improved through intensive study of word-formation concepts, as pointed out by Hannounah (1999). Additionally, the words produced through the clipping process are highly challenging, as Stageberg and Oaks (2000: 136) indicate that clipped words are prevalent in the speech of specific individuals and are not sufficiently used by language speakers to instigate changes in a dictionary.The term related to word formation ‘inflection’ is primarily described in intermediate and secondary school textbooks, and it is needed as the correct response for item (1), indicating that the EFL college learners in question experience no difficulties in managing it, achieving (54%) correct answers in the production section of the questionnaire. This positive performance might be attributed to the idea that prior knowledge has a beneficial impact on learning, as argued by Schmidt (2002). Item (6), which asks for the word formation term ‘affixing’, does not pose a significant challenge since (53) EFL learners in this question can respond correctly, as demonstrated in Table (2) and depicted in Figure (2), due to the fact that this word formation term is also connected to other grammatical subjects, with Stageberg and Sciarini (2006) suggesting that based on the Behaviorism Theory in language acquisition, FL learners show greater interest in concepts applicable across various fields, such as morphology, which finds relevance in both language and biology. The learners in this study achieve (52%) correct answers in item (4), which asks for the general morphological term ‘stem’ as the appropriate response.General or primary terms and ideas in a specific linguistic field typically receive significant focus from foreign language learners who tend to prioritize overall and key concepts over sub-concepts and terms or secondary terms and ideas, as asserted by Steinberg and Sciarini (2006: 211). Regarding item (2), which pertains to the word-formation term ‘conversion,’ this received (62%) of the collected responses, as illustrated in Table (2) and displayed in Figure (2). This serves as an indication of satisfactory accomplishment in English morphology concerning the production level.

Conclusions

The present study reaches the following conclusions:

1. Psycholinguistic factors significantly influence Iraqi EFL college students in acquiring English morphological concepts.

2. Iraqi EFL college students show significantly better performance in General Morphological Terms compared to Word-Formation Terms at the recognition level (65% in General Morphological Terms and 38. 71% in Word-Formation Terms).

3. The achievement of Iraqi EFL college learners in General Morphological Terms is markedly superior to their performance in Word-Formation Terms at the production level (57. 33% in General Morphological Terms and 40. 28% in Word-Formation Terms).

4. The Word-Formation Terms: acronymy, borrowing, back-formation, and blending are the morphological terms that Iraqi EFL college learners struggle with significantly more in English morphology at the recognition level.

5. Iraqi EFL college learners significantly encounter difficulties in the Word-Formation Terms: compounding, clipping, and back-formation at the production level.

6. Iraqi EFL college learners achieve considerable success, to some extent, in recognizing and producing the Word-Formation Terms: inflection, suffixing, conversion, and coinage.

7. There is an urgent necessity for the instruction of English morphology beginning in the first year in Departments of English in all Iraqi Colleges of Education, Basic Education, and Arts.

Reference

Alberts, M. (1998). Terminology. 3rd International Conference of

Lexicography National Language Service: Pretoria.

Al-Jubouri, Najat. (2014). A Language Teacher’s Guide to Assessment.

Baghdad University Press.

Al-Khuli, Muhammed Ali. (2009). An Introduction to Linguistics. Amman:

Dar Al-Falah.

Andrew, Carstairs-McCarthy. (2002). An Introduction to English Morphology:

Words and Their Structures. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bauer, L. (1983). English Word Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Bloomfield, L. (1933). Language. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Bollinger, D. L. (1968). Aspects of Language. New York: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich.

Crystal, David. (1985). A Dictionary of Phonetics and Linguistics. Oxford:

Basil Blackwell.

Fromkin, Victoria, Rodman, Robert, and Hyams, Nina. (2017). An

Introduction to Language. 11th Edition. California: CENGAGE.

Garman, Michael. (1990). Psycholinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Hamash, Khali and Abdulla, J. Jamal. (1968). A Course in English

Linguistics. Baghdad: University Press Baghdad.

Hannounah, Yasmin Hikmet Abdul-Hameed. (1999). An Introduction

Coursein General Linguistics. Baghdad: University of Baghdad Press.

Hannounah, Yasmin Hikmet Abdul-Hameed. (2008). English Syntax for EFL

College Students. Amman: Dar Al-Falah.

Harrison, Andrew. (1983). A Language Testing Handbook. London:

Macmillan Press.

Hartman, R. R. K., and Stork, F. C. (1972). A Dictionary of Language and

Linguistics. London: Applied Science Publishers.

Kageura, K. (2002). The Dynamic of Terminology: Descriptive Theory of

Term Formation and Terminology Growth. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins.

Miller, G., and Gildea, P. (1987). How Children Learn Words. Scientific

American, 27, 94-99.

Nast, Raja, T. (1980). The Essentials of Linguistic Science. London:

Longman Group Ltd.

Pyles, T. (1972). The Origins and Development of the English Language.

New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich INC.

Richards, Jack C., and Schmidt, Richard. (2002). 3rd Edition. Longman

Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. England:

Pearson Education Ltd.

Schmidt, Norbert. (2002). Applied Linguistics. London: Arnold.

Stageberg, D. Danny and Sciarini, V. Natalia. (2006). An Introduction to

Psycholinguistics. London: Pearson Education Ltd.

Stageberg, N. (1981). An Introductory English Grammar. New York: Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, Inc.

Stageberg, N., and Oaks, D. (2000). An Introductory English Grammar. New

York: Harcourt College Publishers.

Trask, R. L. (2014). A Student’s Dictionary of Language and Linguistics.

London: Routledge.

William, D. A. (1972). Linguistics in Language Teaching. London: Arnold.

Yule, George. (2010). 4th Edition. The Study of Language. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.